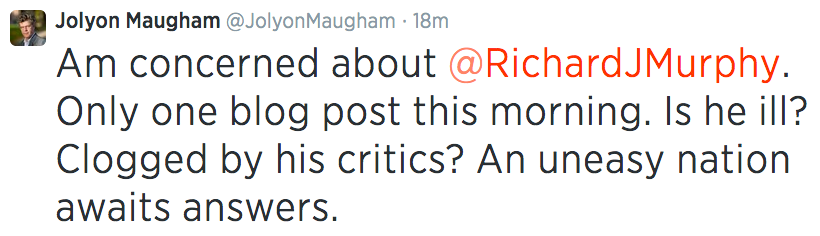

I note Jolyon Maugham is worried about me this morning. At just after nine this morning he tweeted:

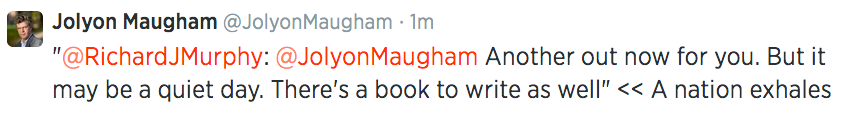

I was able to reassure him a few minutes later when the next was out, and he responded:

This follows a series of exchanges between us over the last couple of days where we have most certainly disagreed - but good humour has been retained. I make the point for good reason: it can be done.

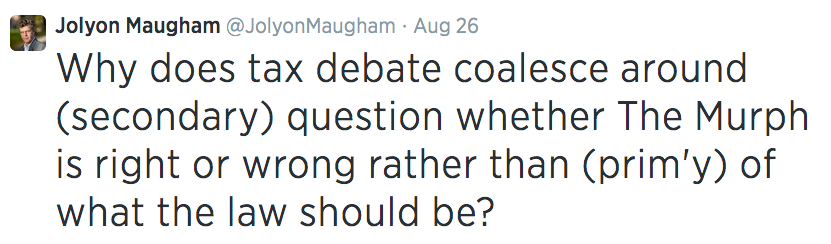

But in the middle of all that debate Jolyn made another point that I found interesting, and surprising, when writing about me. He said:

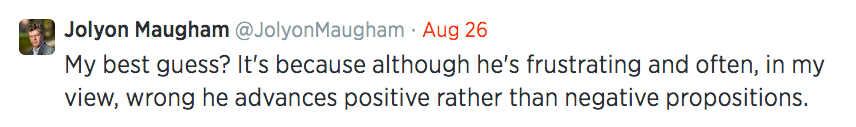

How followed that up with:

and

And Jolyon's right. Whether I'm right or wrong (and I have an opinion on that) from the beginning of my work on tax justice I have been solution focussed. It's never been enough, as far as I am concerned, or as far as the Tax Justice Network has been concerned, to point out that something is wrong. It has always been necessary to point out what can be done about it.

Now I am not saying there aren't others who do not propose tax reform. Judith Freedman did with the general anti-avoidance principle, and that was important. And after that I struggle to think of more examples until I come to the right wing and the IEA with flat taxes, curtailing the state and so on, none of which have a hope of achieving any significant political support.

This suggests that Jolyon's conclusion is appropriate. The tax profession expends enormous amounts of energy on negativity. Positive thinking that is within the sphere of political credibility is rare. And that's a shame as far as I'm concerned.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Richard, the problem is that the tax profession think it is their job to lobby for tax rules which favour their clients.

For example, I’ve never heard a UK tax advisor seriously suggest that the UK should introduce further restrictions on interest deductibility for large UK MNCs used to fund overseas subsidiaries. This should have been a very clear and logical quid pro quo for effectively exempting all foreign income under the new CFC rules (together with dividend/capital gains exemptions).

Ironically this means that large MNCs now do not need as much advice from the tax profession on how to “manage” their UK corporation tax position because the rules are much more straightforward and many are swimming in UK tax losses.

Similarly they do not seem to care that the recent corporation tax cuts at the same time as cutting capital allowances have effectively led to large banks receiving a huge windfall at the expense of companies making real investment in the UK.

Oddly, I have in my time been encouraged by some Big 4 partners to lobby for that interest restriction

They were too frightened to say it themselves

Why is the worldwide debt cap insufficient?

Let’s start with the fact that it appears to have little impact

Well, contrary to what DblEntry suggests above, there was a quid pro quo for introducing the new CFC regime and dividend exemption, and that was the worldwide debt cap. You say it has little impact – why? what would you change about it?

Because WWDC is a measure to stop abuse, but didn’t change the policy that it is acceptable to get a UK deduction for UK borrowings to fund overseas acquisition.

So if your worldwide group is worth 1000 and your UK operations are worth 100, you can now only have a maximum of 1000 of debt. People were setting up structures with 2000 of UK debt, and WWDC stops that; but there’s a pretty solid argument the restriction should be to 100.

Stuart below is right and in fact even Luxembourg and Netherlands both have this rule limiting the acceptable debt to 100 (in his numbers).

perhaps the reason the reason Richards comments are subject to so much debate is precisely because he offers alternatives. this strikes right at the heart of the “there is no alternative” to austerity mantra. and so he is a spearhead, a highly visible and therefore troubling spearhead in the eyes of his enemies. hence he is what they focus on.

so Jolyon is right; the more such spearheads exist (regardless of what path they take) the more difficult the enemies defense.

I’ve never accepted TINA

The Green New Deal is another example of that

Why dont the uk transfer pricing and thin cap rules stop this? If someone can get a bank to lend on the same terms then why isn’t this ok?

Scale is the issue

A small comparison is immaterial to a major intra group loan

Though it is a point not often taken

Those rules only apply to uncommercial arrangements. If a UK group borrows money from a third party bank to buy a French group, then the arrangements are entirely “arm’s length” so the anti-avoidance rules don’t apply.

The issue that that there is a broad principle you usually see in tax where you allow deductions for expenses incurred in obtaining taxable income. Hence, if you sell a capital asset you are allowed to deduct the original cost of buying that asset; if you run a trade you are allowed to deduct expenses of that trade; a business is usually allowed to deduct any VAT it incurs from the VAT it charges its customers; and so on.

Similarly, generally speaking, if the income isn’t taxable then you don’t get a deduction for the expense. For example capital profits are generally not subject to income tax so you can’t get an income tax deduction for capital expenditure; dividends received from a foreign company are exempt from UK taxation and so no tax relief is available for any tax paid overseas in relation to that dividend; and so on.

The UK’s rules on interest deductions for investment companies are weird because the UK allows a deduction for the interest expense incurred in obtaining a French business: but we often don’t tax the French business at all (i.e. dividends and capital gains are often exempt). It’s a weird mismatch, and one that doesn’t exist is most other countries.

You hit the absurdity of our rule bang on the head

That’s wrong for two reasons. First, a multinational would generally prefer to have debt in the French company than the UK parent, as the rate of French corporation tax is higher (and the various French limits on deductibility would have little impact in this case). Second, if the debt was all lent at the parent level, the banks would require a guarantee from the French subsidiary, and the UK transfer pricing rules would then kick in to restrict deductibility of the UK debt. In practice the acquisition debt is usually “pushed down” to (in this example) the French group immediately after the acquisition.

So I don’t see this kind of planning – if anyone thinks it does happen then they need to show some actual examples.

Also – it’s a non-starter to propose a rule that permits a deduction to fund a UK acquisition, but denies a deduction to fund a foreign acquisiton. Clearly contrary to EU law.

Have you not noticed the OECD think this a major issue ion international tax avoidance?

Might you be wrong in that case?

No, I hadn’t noticed that – BEPS Action 4 is about related party debt, not bank debt. I can see some countries may be concerned about over-leveraged bank debt, but in the UK it’s not a major issue for the reasons I explained about, and hard to fix because of the EU law angle. Anyone that disagrees should show an example of a company that’s artificially reducing their tax by putting a disproportionate amount of their external debt in the UK.

The argument is to disallow debt

You have the wrong end of the stick re the EU

Really? Why?

To create balance with equity

A long time issue of concern in CT to which various responses have been offered

This is one

Isn’t that a separate point? But it doesn’t matter – any proposal that debt funding UK subsidiaries is favoured over debt funding foreign subsidiaries is almost certainly contrary to EU law.

I am suggesting for both

I really am an obsequious little tw@t.

lol looks like i might have done my good deed for the day!