IPPR issued a new report on macroeconomic management yesterday. It's one of a series of reports link to their Commission on Economic Justice. To save time these are their recommendations:

In this context, we propose three areas of structural reform to UK macroeconomic policymaking.

1. We propose new fiscal rules to guide government policy, mitigating against both deficit bias and surplus bias. These include the separation of borrowing for current spending from borrowing for investment. Borrowing for current spending should be balanced over a rolling five-year period. Public investment (which supports long-term growth) should have a separate target as a percentage of GDP. Overall debt should be determined on the basis of its long-term impact on the economy. The proposed rules would provide stronger protection of government investment during recessions and increased flexibility to increase overall spending temporarily if interest rates are at the effective lower bound.

2. We propose that the Treasury considers revising the Bank of England monetary policy mandate. The Bank's Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) should be asked to target one or both of unemployment and the level of nominal GDP, either alongside inflation or as intermediate guides to a primary inflation target. This would reduce the risk of monetary policy being over-tightened during a recession when inflation was the result of an external price shock.

3. We propose a significant institutional reform of the UK's macroeconomic framework in order to provide an alternative means of delivering a spending stimulus when interest rates are very low. This would be superior to QE in terms of economic reliability and democratic accountability. We recommend the creation of an NIB, which under normal circumstances can help to provide countercyclical lending to support socially and economically productive investment in line with the priorities of the elected government. In addition, and to reduce reliance on QE, we recommend that the Bank of England is given the power to ‘delegate' an economic stimulus to the new NIB when interest rates are at the effective lower bound and government fiscal policy is believed to be overly restrictive. This stimulus could take the form of increased lending for business growth, housing, innovation, and social and physical infrastructure. To ensure the extra lending can always be funded, we propose that the Bank of England is able to coordinate any delegated stimulus with additional purchases of NIB bonds from private investors.

Together, these proposed reforms to the UK's macroeconomic framework would significantly increase the chances of effective policymaking in response to the next recession, while also retaining — and in some cases improving on — the balance between democratic accountability and economic effectiveness.

There are real issues here. Not with the third recommendation of course: that's people's quantitative easing (or green QE as it was once known) by any other name, pretty much exactly as I proposed it in various forms (I even summarised the 2003 origins of this idea on the blog yesterday afternoon, by chance). I am, of course, pleased that people are now realising that this really will be the only game in town when the next crash happens.

My problems are with the first and second proposals. To summarise the concern, I cannot fit either with economic justice. Let me explain.

Problem 1 - the commitment to the status quo

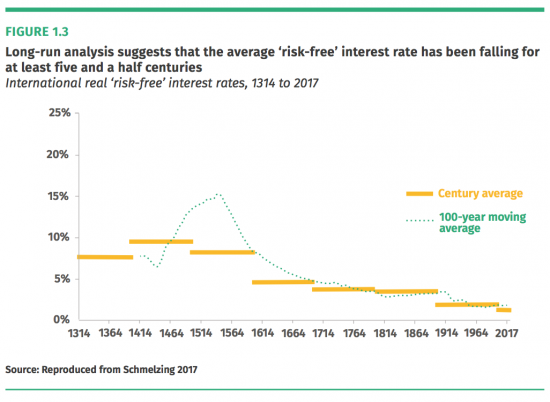

The IPPR paper explains the problems with monetary policy. It uses this graph to assist the explanation:

The reality is that interest is dying: rates are declining and there is no evidence that this is going to change. What that means is that there is no chance that monetary policy can now play the role it did in the economy in the past: the headroom that was required for it to do so cannot be recreated.

Nor is it desirable that it should be. The report notes that base rates of around 5% would be required now if monetary policy were to be effective in a future recession. But such rates would induce a recession. What this means that whatever merit monetary policy once had (and that's open to question) has gone and is not likely to be returning to the political scene for a very long time to come.

But in that case the assumption in the report that the Bank of England should continue to have a fundamental role in managing the economy is, in my opinion, just wrong. The influence here appears to be Simon Wren-Lewis. For the record I have nothing against Simon: he writes a lot of sense on occasion. Bill Mitchell's treatment of him is absurd, in my opinion, and unhelpful. But I do remain baffled by much of Simon's economic reasoning. Although, as the report notes, he wrote in 2009 recognising the power of a hegemonic consensus in economics that mandated an orthodoxy that was not necessarily helpful, and he has also acknowledged MMT (unlike many other economists) he remains committed to the two fundamental harmful ideas that underpin this IPPR report.

The first is Bank of England independence. Leaving aside the fact that the effective demise of monetary policy removes any fig leaf of cover for this policy that it once had, there are major reasons why this policy is wrong.

The first is that it is a sham. As I have written in the past, the Bank of England Act of 1998 makes it quite clear that a Chancellor can always take back control if they want to: no Governor would ever ignore that reality. The veneer of independence does then have a different role as it does not actually exist.

Second, that different role is to remove power from central government because, as the IPPR report says it is believed that:

[O]ne of the key observations of the UK's present macroeconomic framework is that elected Chancellors are prone to ‘deficit bias'. This insight was key to the design of Bank of England independence and the current macroeconomic assignment as a whole.

In other words, the Bank of England is meant to stop government spending, even when there is need, so that monetary stability is mainatianed for the sake of financial markets.

This, I suggest, is not the route to economic or social justice. Nor is it democratic. The belief that the Bank of England should, despite this, stay in charge that runs through the report is wrong, but is always there, to the extent that it is said that:

We propose that in such circumstances [a downturn] the MPC be given the power to ask the National Investment Bank to expand lending in the real economy — for example, either by expanding existing projects or bringing planned projects forward — at a volume estimated to equate to all or part of the interest rate cut that the MPC would otherwise have wished to make.

In other words, in this plan it would not be for government to decide if additional spending was required in the economy, but for the Bank of England.

I can see no justification for this. IPPR has to place its confidence in democracy and not in power elites. The whole policy of supposedly independent central banks is about giving power elites control. That is not what economic justice does. IPPR have this policy wrong.

Problem 2 - A fiscal rule

The IPPR report slavishly adopts the current Portes and Wren-Lewis fiscal rule that Labour made policy in 2016. This is amother serious mistake. There are two reasons.

First, we have no need for a fiscal rule. We have our own central bank. We have our own currency. As Gavyn Davies says in the FT this morning:

Any country with a conventional central bank can ultimately create all of the money it needs to remain technically solvent on domestic debt.

Second, the reality is that QE can prevent debt escalation. There is then no need for a fiscal rule.

Indeed, this is apparent in the formulation of the Portes and Wren-Lewis rule, as adopted by IPPR, which provides that:

[F]iscal rules should be allowed to be temporarily suspended at the request of the Bank of England when its MPC judges that monetary policy is constrained by the effective lower bound. This would free fiscal policy for discretionary demand management when monetary policy is less reliable.

As noted above, this will always be true now: interest rates will be at or so close to the effective lower bound in the UK for all foreseeable time to come meaning that, using the noted logic, there is no case for a fiscal rule. So why have one except to pretend that the government cannot spend and so to provide cover for austerity? I cannot see another reason. This then brings me to my core concern.

Problem 3 -picking the wrong priorities

My biggest problem wih the IPPR report is that it picks the wrong priorities. This is apparent from its suggested priority for the new Bank of England mandate that it proposes, where it says the priority should be unemployment and the level of nominal GDP. Apart from hinting at an unhealthy concern with the Phillips Curve, these priorities are just wrong.

Nominal GDP growth has not delivered economic justice. Indeed, the possibility that growth might cause harm in the future has to be acknowledged because of its environmental impact. But there are issues too with picking on unemployment.

This implies that any job will do. It won't. That's what we have now, and serious social and economic injustice exists as a consequence. It is not just jobs that we need. We need good jobs, with high productivity, requiring solid training, and so rising median wages.

The IPPR targets imply trickle down can relied upon to transform growth into wage increases. We now know that is not true. IPPR should not be supporting such a mandate in that case. The goal of economic policy, in which the Bank should have a secondary role, should be full employment with rising median pay. That is a mechanism to deliver social justice. The IPPR goals are not. They need to be revised.

Summary

IPPR is right to tackle macro. And they have got People's QE right. But social and economic justice requires that we break the hegemony that has created the injustice we are suffering. This report does not do that. As such it fails in its goal. I hope it might be revised.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

I agree with every word of your criticism of the IPPR report. It’s yet another example of wanting to hold on to the status quo no matter what ; as though if they finally admit that government spends and taxes a dam will burst and we’ll all be washed away into a deep pit filled with worthless Weimar Republic banknotes. And they call themselves progressives !

Not so very radical then is it ?

I’m curious as to why interests rates have been falling for five centuries and you say they are not likely to pick up.

In the short term I can see it would cause chaos and collapses, but I don’t see why that is a long term prospect. (Assuming a government were to adopt some sensible economic policies)

@Andy: I’m curious as to why interests rates have been falling for five centuries and you say they are not likely to pick up.

Good question. I am guessing transition from gold to fiat money + globalisation.

Plus better information reduces the risk premium

“Plus better information reduces the risk premium”

Aye, that’ll be why I couldn’t a loan when I needed one. !!

‘Fraid so

You and all who get offered loans at exorbitant rates

Charles Adams says:

“Problem 1: Completely agree, monetary policy is useless when interest rates are less that say 2%.”

When inflation was the big issue ‘they’ used to say that changes in the interest rates (although they produce instant hiccups in the FX markets and banking share prices) take about 18 months to show up in the real economy.

Plus of course, since it is reckoned that a 3%drop in interest rates is what is required to deal within impending recession a 2% rate rules that out without completely re writing the way banking works.

That’s not to say a banking sector working on negative rates is not possible. It’s just never been tried. Having said that, when the Base rate is below the rate of inflation that’s exactly where you are in real terms.

Lets not forget that historically low interest rates are essential to a monetarist, financialised, neo-liberal regime where rent-seeking via leveraged asset-price speculation is the main game.

Pre-GFC, lower rates were a preference and a priority. Post-GFC, near-zero rates (and QE) have been a necessity of survival to keep the main game alive. Now more that ever. We saw what happened to the Dow Jones and other main indexes earlier this year and that was on the merest rumour of rate rise.

So in answer to Andy’s question on a grand (500 year) timescale interest rates will rise again post-crisis, post GFC2 when the current regime collapses and the main game as we now know it is well and truly over.

At any rate I don’t think that we can put the current liquidity trap down to a natural (or unintended) flow-on from globalisation or the transition from gold standard to fiat money. It has been a deliberate, Greenspan-style, engineered process that has exhausted its potential and found itself permanently stuck at the zero lower-bound.

So you think we are heading for a 500 year inflexion point?

Are you sure?

No I just think that liquidity trap definitively signals the end of neo-liberalism; being that system where monetary policy was ascendant and fiscal policy repressed. When neo-liberalism goes the liquidity trap effectively goes with it and rates need no longer be glued to the zero lower bound.

I’m not exactly sure what will happen with interest rates after that but the variability of them will probably be greater (remembering, for example, that 3% is 6 times is greater than 0.5) Generally there will no specific reason to keep rates near zero.

The IPPR graph is interesting though. I see the medieval church’s views about usury in a whole new light.

To be clearer, historic change is afoot but beyond that interest rates could still remain low in historic terms without being paralysed like they are now.

This latest report and report series from the IPPR merely conforms to their normal pattern;

– pick a topic of current interest.

– splash a report out quickly.

– make sure that the introduction hints at radical approaches and solutions.

– ensure nothing of the sort is contained in any conclusions or recommendations.

It’s a shame but that’s what they do.

Problem 1: Completely agree, monetary policy is useless when interest rates are less that say 2%.

Problem 2: I think the purpose of a fiscal rule is to state your intentions to the world. I think this could be sensible as long as the rule is appropriate. Labour’s fiscal rule seems pretty much the same as the plan of the current government. I cannot understand why any one wants to eliminate the deficit as that means that all new money needs to be created via private sector debt where interest rates are higher and the forward look is too short term to meet the goals of infrastructure investment and long term sustainability. They try to make a distinction between current spend and investment but this is very artificial – e.g. your best investment might be to spend more on education which is current spend as an investment in the future.

The question is can we think of a good fiscal rule. I believe MMT would tell us that government spend should be regulated to maintain inflation at less than some preferred value.

Problem 3: again completely agree, I highlighted that GDP is the wrong metric here

https://braveneweurope.com/charles-adams-the-measurement-problem-in-political-economy-a-solution

and suggested that median disposable income would better but that still does not address the sustainability issue so there has to be a sustainability clause.

Thanks Charles

Charles,

I am so glad that you made the point about education etc. It is the first thing that popped into my head when I saw that part of the IPPR’s recommendations.

From the IPPR’s point of view they might answer by seeking to tax the rich (fairer tax) to fund “current spending”. From an MMT perspective that answer partly misses the point of what tax is for – which may be the IPPR’s problem (or one of them).

As to this question of yours:

“The question is can we think of a good fiscal rule. I believe MMT would tell us that government spend should be regulated to maintain inflation at less than some preferred value.”

Would that not simply be another Taylor Rule in effect but one that expands its scope from the central bank and into the realm of democratic government?

Come to think of it, looking back on that last comment it probably requires a clarification:

The Taylor Rule takes the given inflation target and imposes a formulaic rule where everything else (growth, employment etc.) has fit in with that target regardless.

What I am trying to say is that the appropriate rate of inflation might change with different (macroeconomic) circumstances and the way those variables relate to the rate of inflation might also change.

Neo-liberalism sought to replace the democratic conversation with with set rules and targets. I think the best rule is to have no set rules. I think that a leader or political party can state their intentions in terms of social goals or aspirations without subordinating those goals to some contrived, theoretical target.

I think sound judgement – or the rule of thumb – is the best rule

A rule that only applies to the central bank is a sham

This is a nicely argued post. Three additional points I think need mentioning.

Firstly, it’s pointless, for example, with a socialised healthcare system for a government to engage in capital spending programme on say building additional hospitals and then not ensuring government current spending is sufficient for them to operate, staffing, etc.

Secondly, as Stephanie Kelton and Randy Wray mention the so called Bernanke Great Moderation in inflation can be viewed as being heavily influenced by China’s developing economy along with China’s pegging of the Yuan to the American dollar and other currencies to achieve price point in global markets. Of course there’s also subsidising of Chinese industry by deficit spending through state banks writing off or rolling over bank loans to industry.

http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2018/01/answers-from-the-mmters.html

Finally, it would make an interesting topic to explore the IPPR graph in regard to the steady international fall of “risk-free” interest rates. What do they mean by such rates and why are these falling.

I wish I had the time….

This is only a hunch, but Marx thought the trend of profit was downwards and I suppose the question is : why should that not apply to money made from money . In a globalised world there is always the possibility that whatever your product is, if it is traded internationally, as money is, then you might be undercut . The GFC undoubtedly had an impact in this direction if the last ten years are anything to go by . It’s the race to the bottom by any other name.

Schofield,

In common, financial theories such as CAPM ( the Capital Asset Pricing Model) the risk-free rate is that at which there is notionally no risk. The return on government bonds (face value) is often used as a benchmark for the risk-free rate.

The point of the idea is that it provides a basis for comparison such that your investment that involves some risk should provide a rate of return that is higher than “the risk-free rate”.

Richard,

What we are seeing with IPPR’s recommendations is probably the first example co-opting PQE into the mainstream. That in itself is not bad, per se, but they are doing it in the worse possible way.

They are not taking the full idea in context as a productive, socially progressive, change of approach and normalising it. The fundamental change isn’t part of their story. Intentionally or not the IPPR are taking the core device of PQE out of context and adapting it as a means to rescue the current system. That was always a risk I suppose.

It happens in politics and culture as well as economics. A radical idea that seeks fundamental change is neutered, diluted and absorbed by its very nemisis. Capitalism, like fashion, can be very good at adapting. There are ways to fight that but one needs to know that its happening in order to do so. To that end I am glad that you have seen the error in this IPPR report.

I agree with your risk assessment

It is seen as an emergency aberration to be permitted by the BoE by exception

That is so wrong….

“It is seen as an emergency aberration to be permitted by the BoE by exception”

How often have you seen a temporary fix become a feature of life ?

Just making do ‘for the time being’ is a great way to overcome the fear of change.

It works with mission creep too.

But this policy needs to be embraced positively

“But this policy needs to be embraced positively”

I don’t disagree, but I sense somebody , if not actually shifting their ground perhaps ….shuffling a little (?)

Never forget the importance of ‘face’.

PS.

Marco is seeing the same shuffle. And I agree with both of you that it’s not we’d like to see. What Marco describes as “the full idea in context as a productive, socially progressive, change of approach and normalising it.”

But there’s no way get from where we are to that in one step. It just isn’t going to happen. What it does represent is an acceptance (I suspect) that QE works, has worked, in the sector of the economy it was applied to in a state of near panic, and that if applied to the underpinning real economy it just might put some semblance of a cushion under the air gap between for example company valuations and their current fantasy share prices. I don’t see any other way that GFC2 isn’t inevitable, sooner or later.

GFC2….the sequel

And at least as bad as the last one

Andy makes a fair point about the grudging path of change. As for this observation:

“I don’t see any other way that GFC2 isn’t inevitable, sooner or later”

GFC2 is inevitable. Which needn’t be a bad thing entirely.