Greece is in crisis. The crisis has many dimensions. It is a debt crisis. It is a banking crisis. It is a currency crisis. And now it is a tax crisis. It has been reported that Greece's tax revenues have fallen by a third in 2012[i]. In a country that was suffering a loss of maybe €19 billion a year as a result of a 27.5% shadow economy before the current crisis erupted[ii] this leaves the country's government with a chronic shortage of revenue.

The consequences of the Greek tax crisis

The consequences of this shortage of revenue are that the Greek government cannot now settle its short-term debts within the country[iii], let alone meet its external obligations. It is predicted that the entire structure of government in Greece might collapse very shortly as a consequence. This blog addresses the resulting issues. It is also available as a PDF.

The tax justice dimension to this crisis

To those who believe in tax justice this latest development in the Greek economic crisis is unsurprising. We think[iv] that there are five reasons to tax[v]. Tax is used to:

- Raise revenue;

- Reprice goods and services considered to be incorrectly priced by the market such as tobacco, alcohol, carbon emissions etc. and by providing tax reliefs e.g. for childcare;

- Redistribute income and wealth;

- Raise representation within the democratic process because it has been found that only when an electorate and a government are bound by the common interest of tax does democratic accountability really work[vi];

- Reorganise the economy through fiscal policy.

These are the 5 Rs of taxation.

What we also argue is that people will pay tax voluntarily when they perceive that a tax system that fulfils these goals is in place. The corollary is, of course, that tax will be withheld when there is no confidence in the willingness of those in power to fulfil these objectives. The people of Greece are withholding their tax revenues precisely because they no longer think that their government has the intention to fulfil their side of this bargain.

A government committed to repaying foreign debt created as a result of market failure is not dedicated to correcting market imperfections; it is exacerbating them.

A government that is taking funds from the very poorest in its community to sustain the banking community and its depositors - who are by definition amongst the better off - is committed to upward redistribution. In a democracy that is bound to fail.

A government committed to meeting the needs of foreign bankers is not committed to democracy: it has to ignore the democratic interests of its people at home to do that, as indeed has happened with the appointment of technocratic governments in Greece.

And any suggestion that Greece is somehow managing its own economy is of course just a myth when all it is seeking to do is repay external debt at the behest of its creditors and largely under their control.

The result is obvious; people are refusing to pay their tax to help a government make payments that they know are not in their interests and which are not justified by the social contract with their government that is the foundation of their democracy.

That social contract in Greece has failed precisely because four of the five reasons for taxing its people that are the foundation of tax justice in that country are being very deliberately ignored by its government in an attempt to meet the demands of external authorities. It is a failure that was as inevitable.

Who Greece is paying

In 2010 the IMF published a paper on financial interconnectedness[vii]. As they argued:

Countries are financially interconnected through the asset and liability management (ALM) strategies of their sovereigns, financial institutions, and corporations. This financial globalization has brought benefits as well as vulnerabilities. In particular, the speed with which illiquidity and losses in some markets can translate into global asset re-composition points to the risks of interconnectedness.

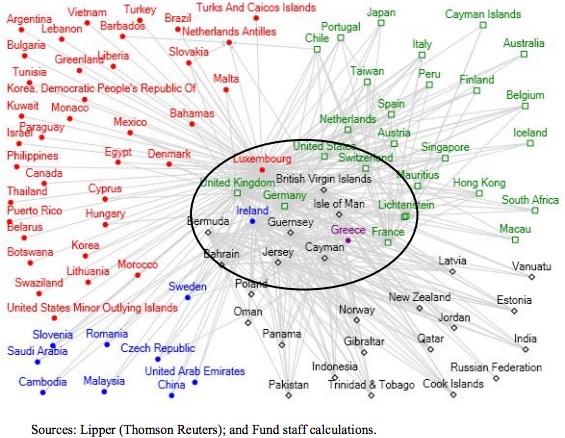

As the Fund then showed, in the case of Greece the interconnectedness looked like this:

As the Fund noted:

The obligations owing by Greece split into four clusters (i.e., countries that together form more of a closed system), centred around a set of core connections that are closely linked to Greece: (i) a red cluster of countries with access to funds domiciled in Luxembourg; (ii) a black cluster with access to funds domiciled in the offshore centres of British Virgin Islands, Jersey, Cayman, Guernsey, and the Isle of Man; (iii) a blue cluster with Ireland at the core; and (iv) a green cluster of the U.S. with several key European and other countries. Greece is interconnected with each of the central nodes of these clusters. This close interconnection across other core countries suggests why asset reallocations and flows might have been large systemically, with potentially significant impact on countries such as Ireland.

What is obvious as a result is that Greece is largely indebted via tax havens to a global financial system that behind the anonymity of the financial architecture it uses is demanding repayment from Greece at cost to the people of that country in what may well be a vain attempt to ensure that the offshore financial architecture of banking survives.

It is not clear how many in Greece will see it this way; their reactions may be more instinctive. There can however be little doubt that the harsh reaction[viii] of Fund managing director Christine Lagarde is informed by the understanding of that paper published by her own organisation.

It is of course simplistic to say that the crisis Greece faces is one that sets the offshore shadow banking elite against the people of a struggling democracy, but it also happens to be true.

The lesson to be learned from Greece

There are numerous lessons to be learned from this situation.

The first is that there is a tacit agreement, not imposed by law but by social consent to pay tax, even in a country like Greece with an undoubted history of above average tax evasion. This agreement can, and has, failed.

Secondly, the demands being made of Greece are dangerous. In this context[ix] the thesis of Harvard economist Dani Rodrik in his book ‘The Globalisation Paradox' is important[x]. He argues that there is a trilemma within the global political economy. As he puts it, there are three characteristics of which any given economy can only have two at any given time. The three sides of his trilemma are the nation-state, democratic politics and deep economic integration. Greece has tried deep economic integration, as the Fund diagram shows. But if that it is to be maintained then it can only be at cost to its status as a nation state or its democracy. Rodrik's point is that will be sacrificed if its obligations are to be met as planned by the IMF and others at present.

Third, as a matter of fact, even if its obligations were to be met the cost would be considerable: even if the pre-crisis Greek tax gap could be closed the tax raised would take 17 years to pay off Greek government debt. The cost of doing that is obvious: the tax gap in question was already 112% of Greece's annual health care budget. The chance of social progress if that debt is to be repaid is remote.

How to tackle the failure of tax justice in Greece

If the people of Greece refuse to pay tax to their government nothing that the IMF, European Commission or anyone else can impose can make them do so within the constraints of a democracy. Mass disobedience of this sort is an expression of democratic will.

The crisis in Greece is now, therefore, one where a decision has to be taken. Either Greek democracy and the right of Greece to be recognised as a nation state has to be respected or, alternatively democracy has to be stated to exist at a European and not national level (which is implausible since that would not be true of the rest of Europe) or Greek democracy has to be foregone to enforce payment to an integrated economic financial system.

Tax justice is premised on the belief that tax must be charged by democratically elected governments. It follows that in this case Greece and Greek democracy must come first at this moment and the rights of the financial system must come second.

If this is the case then what is now essential is that it be worked out how the international financial architecture can be reconciled with the paramount need to maintain a democratic Greek state. There are three ways to achieve this.

The first is debt waiver. It is very unlikely that this has gone far enough as yet whether or not Greece remains within the Euro.

The second is a commitment from the international community to ensure that the Greek government remains liquid and therefore able to meet its obligations to the Greek people as they fall due. Without that commitment the process of government will fail and all will lose.

The third commitment is to raise new sources of tax revenue to broaden the tax base, tackle the culture of tax abuse and give Greece a new start. There are at least four obvious ways of doing this, all intended to capture tax revenues that have very largely fallen outside the tax net to date.

New taxes for Greece

a. A withholding tax on interest payments

A withholding tax on the payment of interest to external lenders in existence at this time has to be permitted in the case of Greece and other embattled European economies. That interest being paid has its source in the Greek economy. Greece should be entitled to tax this income arising from within its economy at source, as should other countries in similar situations. The rate should be significant, but realistic. A 25 per cent withholding would seem appropriate. If that were to be done three things would follows. Firstly, the international community would show a commitment to paying Greek tax that would lend credibility to its demand that the Greek people do likewise. Second, very obviously the Greek government would have a new source of revenue. Thirdly, that combined commitment would allow those fighting to save democracy in Greece to command the legitimacy to reform the Greek taxation system to ensure the Greek tax gap was at least reduced whilst the commitment of the government of Greece to meet the needs of its people was maintained.

b. A European wide financial transactions tax

As the IMF data shows, Greece has suffered as a result of the creation of a financial architecture that is out of control and unaccountable. As a result it is seriously under taxed within each nation state. When that financial system operates in the spaces between nation states — as is commonplace for the this type of finance[xi] - it is largely untaxed. Financial transaction taxes are vital is this feral form of finance that seeks to exist beyond regulation is to be brought under control. The European Union has recognised this and has called for a financial transaction tax[xii]. Now the European Commission must deliver one to restore tax revenues within Greece and within the other member states impacted and threatened by the volatility this form of financing has created.

c. A land value tax

Land value taxation taxes the site value of property[xiii]. Determining that can be a little subjective since the value of the building placed upon the land is excluded from consideration, but it is not beyond the wit of any jurisdiction to determine this value, in bands if need be. Land value tax is then levied upon that site value of the property a person occupies. In a country like Greece there is considerable potential to such a tax. First, land is not portable. In that case the tax base clearly exists and it is hard to avoid the tax as a result. Secondly, if the owner of a property cannot be determined the property is taken in lieu of the tax. This tax is, therefore, enforceable. Thirdly, this tax can be made progressive with relative ease by applying differing tax rates to different valuation bands, ensuring that tax justice can be seen to be delivered. The extent to which a land value tax would replace other taxes could be the subject of debate: given the current state of the Greek tax system this tax might have a considerable role to play at present.

d. Taxing Greece's flight capital

No one knows how much Greek money is hidden in tax havens / secrecy jurisdictions. That is because those places do not tell, be definition. That is the problem for Greece and other countries where tax evasion has been an issue, the exodus of capital to tax havens has exacerbated current financial weaknesses, and the loss of resulting tax revenues threatens to undermine democracy. Greece could be tempted in this case to do deals with tax havens — such as the Rubik deals that Switzerland is now offering[xiv] — to recover tiny proportions of the sums they have lost. This would represent a serious error of judgement. Such deals are only on offer from Switzerland at present, only repay a tiny proportion of the tax lost and grant taxing rights to Switzerland in future — and those who have doubt about the commitment of Swiss banks to tax appropriately from behind a wall of secrecy that will remain impenetrable are doubtless justified in stating their concerns. Instead Greece has to demand, and the international community has to deliver, full automatic information exchange with regard to income earned by residents of one state on sums held in another state. Nothing less will do now to tackle the massive crisis for democracy that the free flow of capital without appropriate regulation or taxation being applied has created. This could happen in the first instance by the imposition of the new, and largely agreed, European Union Savings Tax Directive with those states dissenting being subject to tax withholding on all payments into their financial services entities as a corollary of their refusal to permit the disclosure of information on deposits held by those organisations. In this way Greece could begin to recover some of the tax it has lost through tax evasion.

Tax justice — a solution for Greece

What these proposals suggest is that tax justice is a solution for Greece. Indeed, it may be the only solution for Greece that ensures its democracy survives. And it is the only solution that, in or out of the Euro, ensures Greece might be able to pay its way — which is vital if considerable social cost and civic unrest is to be avoided not just in Greece, but throughout Europe.

[ii] http://www.socialistsanddemocrats.eu/gpes/media3/documents/3842_EN_richard_murphy_eu_tax_gap_en_120229.pdf

[v] The first four of these reasons to tax were created by Alex Cobham, then of Oxford University, now head of research at Save the Children. I added the fifth.

[vi] Arguments in support of this idea, which is especially important in a development context, have been best developed, I think, by Mick Moore of the Institute for Development Studies at the University of Sussex. His IDS working paper ‘How Does Taxation Affect the Quality of Governance?' develops the theme, amongst others. http://www2.ids.ac.uk/gdr/cfs/pdfs/Wp280.pdf

[viii] http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/may/25/payback-time-lagarde-greeks

[ix] My thanks to Duncan Weldon of the TUC for this insight

[xi] For a description of how this happens see http://www.secrecyjurisdictions.com/PDF/SecrecyWorld.pdf

[xii] See, for example http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5gBvM0YTzh0YZewJBwNZPlh1W1VGQ?docId=CNG.1e151374da51b67fa780f31d582cb3c9.6b1

[xiii] See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Land_value_tax as a start point

[xiv] For an idea of what these deals are about see http://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/business/Rubik_deals_run_into_trouble.html?cid=31923872

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

My Greek contacts tell me that part of the reason for the crash in tax revenues is the lack of a functioning government. They are waiting for the elections before they pay their taxes – it’s a tradition to withhold tax during an election period, apparently.

Maybe – but then the new government has to deliver

That’s what I’m focussing on

Although Greek debt may have arisen through those naughty Financial Elites now after two bailouts by the IMF / EU and the debt write off the bulk of Greece’s debt is owned by the EU / IMF…

In other words tax payers………when you cancel that debt or steal 25% of the interest payments then you are taking from other tax payers not the elite…..

Explain how it is “Tax Justice” to take money from tax payers who actually pay their tax due in a democratic Country and give it to people in a Country where they refuse to pay tax?

How does the expectation of the Greek people from their Government for social care overide the expectation of the European people that their tax is spent on them and not diverted to Greece?

Democracy in one Country does not overide democracy in another, see the German polls for their thoughts on giving more money to Greece…..Or do their votes not count?

Ah, the argument of the victorious parties at Versailles that led us to September 1939

The wise allow for forgiveness

either Richard can you clarify for the casual reader like me?

Is the money lent to the Greek government really TAXPAYER’S money? I suggest perhaps in the sense of the ultimate ownership but I believe it’ s not money paid by taxpayers and diverted from, say health or education. to be lent overseas. It is digitally created sums backed to a percentage by holdings of central or private banks-or have I got it wrong?

Though, I suppose if Greece, or any other country, were to default would the taxpayer be paying for a bailout of the banks?

You are exactly right

And it’s only been done to save bailing out the banks instead

Of course, in the end we might do both

Is it fair to surmise that the chances of a return to dictatorship for Greece is a possibility?

Likelihood?

The days of military dictatorship have gone. But the type of government that has developed since shares many characteristics with it: Incompetence, Arbitrariness, Amateurism, Secrecy, lack of regard for Fairness and Accountability to name but a few.

We should be careful with this kind of statement:

If the people of Greece refuse to pay tax to their government nothing that the IMF, European Commission or anyone else can impose can make them do so within the constraints of a democracy. Mass disobedience of this sort is an expression of democratic will.

While fully supportive of this statement when it benefits our social democratic aims, we run the risk of neoliberals using this type of feeling as well to validate their own reactionary policies against tax.

I’m not sure that follows

Note I refer to the democratic will

Unless they explicitly seek to repress that will, of course

I believe Richard’s point is very valid. It is very difficult to convince everyone to pay taxes when even MP’s in Greece do not pay tax for half their income as it is legally defined as ‘re-compense’.

The prevailing belief is that politicians use public resources at capricious will and personal benefit. Why should others do differently?

It is finally a legitimacy issue.

Greece as it is now is a recent development, less that a couple of hundred years. In antiquity it went through several phases before finding it self a satrap of Rome. Then it went through the Byzantine and later Ottoman Empires. We assume that it could and should exist as a nation state, but what happens if it has now embarked on a very different course? A people that give up paying taxes for their government will find themselves in another world. And, I suspect, a lot nastier.

Added item, have you seen this one from The Slog today? Wordy, as ever, but what do you make of it?

http://hat4uk.wordpress.com/2012/05/29/crash-2-why-has-the-treasury-revoked-debt-trading-sections-of-a-1939-act-without-telling-parliament/

Collapse of Euro imminent, by the look of it

Slightly off topic here Richard but I have just read that Christine Lagarde doesn’t pay a penny in taxes, anywhere. Apparently it is due to some UN charter regarding employees. So ‘kettle calling the pot black’ and ‘we’re obviously all in this together’. Expletives deleted!!

[…] Richard Murphy blogged it, with a nice short summary of what it means in a longer post entitled Greece and tax justice — the last hope for its democracy: “Greece is largely indebted via tax havens to a global financial system that behind the […]