I’ve been having a courteous debate with Tom Worstall over the last week on the incidence of financial transaction taxes (yes I know it sounds surprising, but it’s also been true). At the end of it the best Tim could say was:

For myself, before we decide to change the taxation system for the globe’s financial markets I would insist that we should only be making changes where we can predict both the effects and the magnitude of them.

He came to this position having failed to knock any holes in my logic on the potential incidence of a financial transaction tax on foreign currency as explained in Taxing Banks. I on the other hand have argued that sufficient data to predict the future and the consequence of all action is never available. In that case we use a priori logic, whatever relevant and reliable data we may have to test and a considerable quantity of judgement to decide what to do since the evidence will always be incomplete and the opportunity for error will, therefore always exist.

The difference in contention between me and Tim is not, however, the weight given to empirical data over logic: poor logic can never be resolved by good data. Good data can support logic or give rise to further questions. Therefore anyone of sound mind has to put sound logic ahead of data: to argue anything else is itself illogical.

Rather though the difference between Tim and me is something quite different: I argue that we have to make judgement. Tim is seeking to deny that although I am quite sure that he knows in doing so he is just using a rhetorical tool to object to change to a status quo which he desires and which I abhor — namely the exploitation of society by banks. I seriously doubt he or anyone could believe that action on taxation cannot take place unless it were possible to predict with the degree of reliability he seems to think essential the effect and magnitude of the change they might create. We’re unable to do that. So Tim is either seeking to deny the reality of the uncertainty inherent in the human condition or he is putting forward an argument that he knows to be false in the hope it will achieve his political aim. Not surprisingly we’ve agreed to differ on the outcome of our debate.

I did, however, then ask him to consider the issue of the tax incidence of corporation tax, which I discussed here. He said:

If, as Joe Stiglitz pointed out can happen, the incidence of corporation tax on the workers’ wages is higher than 100%, then cutting corporation tax will increase the workers’ wages by more than the cut in corporation tax. Even assuming that taxes on labour are raised to cover the lost revenue (that no other measures are taken, such as different methods or taxing returns to capital, or spending cuts) as we don’t think that the incidence of taxation upon labour is more than 100% on labour then labour will be better off by being taxed directly rather than indirectly.

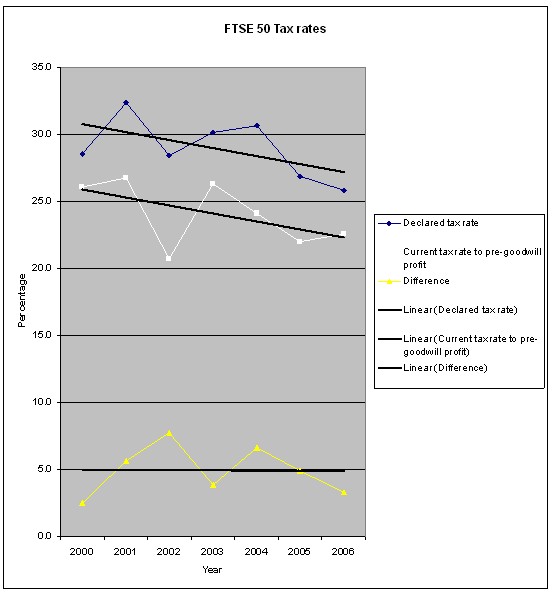

In other words, he thinks that the incidence argument suggests that as corporation tax falls labour rates should rise. Note this does not imply that this must be the case in individual companies: it should be so across the economy as a whole. In other words, if Tim is right as corporation tax rates fall then wages should rise. He is unambiguous about this. It’s an a priori argument which can be tested with data. This is data I prepared on trends in corporation tax in the UK from 2000 to 2006 based on detailed analysis of tax paid by the largest 50 UK companies in that period, published in the Missing Billions in 2008:

The effective rates of corporation tax in the UK fell during this period from 26.1% to 22.5%.

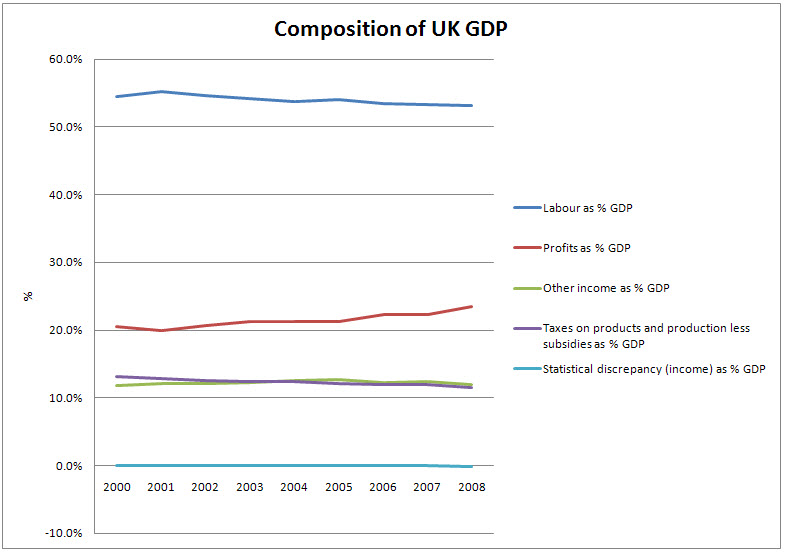

If Tim is right wages should have risen as a result. This graph is based on direct download of Office for National Statistics data and shows what actually happened:

From a high of 55.2% labour share of GDP in 2001 it fell to 53.2% in 2008. The return to capital, however, rose from 19.9% in 2001 to 23.5% in 2008.

I thin on this occasion the data is compelling and unambiguously supports the logic I have presented that corporation tax cuts reduce the return to labour and increase the return to capital. In other words they reallocate income from those who work for it to those who do not work for it: they reallocate income from the poorest to the wealthiest and they make society more unequal and the tax system more regressive as a result.

Of course, data is insufficient in itself to prove a case. The logic has to be right to. But those who honestly believe that the incidence of corporation tax is on labour are few and far between — and it is their work which has, by and large, lead to the crisis we’re now in. Those who do however think that companies do pay tax and that when they do so the incidence is on capital are widespread, and whilst herds aren’t always right on this occasion the logical flow in their argument is so obvious it is hard to contend with. It just helps that the facts support it.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

I think the data and analysis you present is partial. There are many considerations, to pick just 2:

1. The data is presented during a period of economic boom. Returns to capital are more variable than labour and as such during a boom it can be expected that returns to capital increase relative to labour. If you run the data forwards into 2009, it would be interesting to see the impact.

2. The UK is not a closed economic system, returns to capital are also impacted by international variables which have a much more muted impact on the labour market. A global boom will have a more direct impact returns to capital than labour.

Further, the extent to which tax on profits or corporate transactions increases the cost of capital, then it is likely that over the long term returns to capital will increase to reflect that increased cost. The increase in returns will arise from eliminating marginal investments that do not meet the higher cost of capital. In the short term it may also be driven through optimising profit through, among other things, wage restraint. Increases to the cost of capital in the UK would simply make other less “costly” jurisdictions more attractive to international capital flows.

Just because wages fell at the same time that rates of corporation tax fell does not prove a causal relationship any more than saying the following does:

“Whenever ice cream sales rise, so do shark attacks. Therefore eating ice cream makes you tastier for sharks.”

What if there is an underlying causation of both, or another factor that acts as a causal link between the two?

Didn’t the same period (1997-2007) also see an increase in employers’ National Insurance contributions?

If employment costs rise and revenues are constrained, then wages or staffing levels will be squeezed.

I was also under the impression that Corporation Tax was a tax on profits, not wages or income. It could be argued, therefore, that increasing Corporation Tax will reduce net profit, and hence also reduce dividends. This would encourage management to squeeze wage costs to maintain profitability (and their bonuses). So raising Corporation Tax could lead to slightly lower wages, or more likely lower staffing levels. I find it hard to argue the opposite though.

Lowering the rate of Corporation Tax will increase profits. Would employers voluntarily pass this windfall onto their workers? I doubt it. Their first duty is to shareholders. The windfall will therefore go in higher dividends and bonuses.

So, if Corporation Tax goes up, wages go down, but not by as much. But if Corporation Tax does down, wages stay the same.

As for the problem of knowing the unknowable, surely the most sensible approach is to phase in any change gradually. A new tax set at too high a rate could cause asymmetric shocks throughout the economy. Introducing any new tax at a very low level and then raising the tax rate year by year allows you to judge the scale of its impact. It then allows you to extrapolate based on initial data, and reverse or modify the policy if necessary.

That’s a very nice try Richard but I’m afraid that it’s not a win. Your assumption there is that whatever meachanism it is that produces that tax incidence upon labour of a corporation tax works over a 6 year time period. An assumption which suffers from three problems.

1) You’re much more of a Keynesian than I am but even I, neo/classisist that I am, don’t think that economies adjust immediately. Prices, in fact large parts of the economy, are sticky. We would not expect to see immediate movements. But this is a trivial point.

2) There’s a theoretical point as well. The claim is not that “lower corporation tax and wages will rise” it’s that “lower corporation tax and wages, ceteris paribus, will rise”. There is of course a lot more going on in an economy than simply corporation tax rates and the assumption is that it is the effect purely of corporation taxes which will change wage rates. Over this period of time there were of course other things going on in the economy.

3) The third is the important point though. You’re not thinking through the mechanism by which corporation tax rates affect wages. All of the economists who claim that there is a relationship (and this includes our Nobel Laureate, Joe Stiglitz, plus the entire field of those who have looked at the incidence of corporation tax) claim that the incidence occurs as a result of changes in capital investment.

Put very crudely the argument is this: There is a risk adjusted rate of return to capital. In an open economy, where capital is mobile, this will be the global risk adjusted rate. Taxation of returns to capital in one jurisdiction does not change that global risk adjusted rate. Thus, in a jurisdiction which taxes returns to capital, returns will be below that global rate by the amount of the tax.

Lower returns to capital will mean less capital invested: if you prefer, the substitution of labour for capital.

And we know what happens when labour has less capital added to it: labour is less productive. Less productive labour gets paid less.

This is the mechanism which is assumed (and I do repeat, this is assumed by all who study this particular tax). Taxation of returns to capital, in an open global market for capital, will lead to a more labour intensive, less capital intensive, economy than the absence of such taxation would lead to. Yes, average wages in an economy are determined by average productivity in an economy and a more labour intensive economy will have lower wages than a more capital intensive one.

No, we do not expect such changes to happen over an economy the size of the UK’s in a mere 6 years. Capital investment takes rather longer than that to change.

Finally, there have been more detailed attempts to look at exactly this point. Attempts, specifically, to hold the “ceteris paribus” contstraint constant, so that we can look solely at the effects of changes in corporate tax rates.

One of those is here:

http://www.voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/4363

The US provides a nice environment to look at such things. There are 50 states, all with different corporate tax regimes. The 50 states also face roughly the same macro-economic effects at any one time. Thus, changes in corporate tax rates are easier (although of course not perfectly) to study in isolation. Which is what that paper does.

Their conclusion does look robust. Higher corporation tax rates lead to lower worker incomes.

@Andrew

Except tax fell, which somewhat negates your argument, doesn’t it?

@Cantab83

Thank you for agreeing with me

Your logic as noted here is sound:

I was also under the impression that Corporation Tax was a tax on profits, not wages or income. It could be argued, therefore, that increasing Corporation Tax will reduce net profit, and hence also reduce dividends. This would encourage management to squeeze wage costs to maintain profitability (and their bonuses). So raising Corporation Tax could lead to slightly lower wages, or more likely lower staffing levels. I find it hard to argue the opposite though.

Lowering the rate of Corporation Tax will increase profits. Would employers voluntarily pass this windfall onto their workers? I doubt it. Their first duty is to shareholders. The windfall will therefore go in higher dividends and bonuses.

I am arguing with those, who entirely illogically, argue the reverse is true – when the data does not support their case

Richard

Tim

Ah, evidence answers all questions then, except when not in the way you want. Is that it?

Your argument is ludicrous. If tax and wage rate moves are so far apart, as you suggest, suggesting relational causality of the type you suggest is reaching far out into the realms of unprovable fantasy.

And as for quoting Hines in support – given his noted support for tax havens in the face of all the evidence as to the harm they cause, you really don’t think that’s going to cut the mustard do you?

Sorry Tim – but I used data to show your argument does not hold true and that the logical explanation – offered here by others – does hold true. Even then you cannot accept the evidence of your error.

Any sound thinking person will however agree that your hypothesis is wrong, the evidence does not support it and as such allegiance to the idea must e motivated by something else – which they’d reasonably presume is a desire to shift rewards from labour to capital.

I’ve expended enough time and effort on this now: the reality is that there is no evidence to support your claim, which is as far fetched as the assumptions on which Devereux and Hines have constructed it.

Game, the debate is closed. The reasonable person could draw their conclusion now, and I think they have that what ytou are arguing is utterly illogical.

Richard

@Richard Murphy

This debate, or its reasoning, now seems to be a bit muddled. If I try to summarise the positions of Richard and Tim, they appear to be these (please correct me if I have misunderstood you both).

Richard appears to be arguing that reducing Corporation Tax results in lower wages (as evidenced by the graph above).

I don’t disagree with this evidence, merely its causality. As I pointed out above, rises in National Insurance could be a cause of recent wage reductions in this country, or it could just be that there has been a general long-term squeeze on wages that has nothing to do with either Corporation Tax or NI, and is actually driven by other free-market factors: globalisation, outsourcing, reduced employment rights or reduced trade union power. In fact the common factor is probably globalisation. This forces down UK wages to prevent jobs moving overseas. It also forces down UK Corporation Tax to prevent companies from moving their HQ offshore.

Tim appears to be arguing that reducing Corporation Tax would result in higher wages. Is that your position Tim? If so I can see no evidence or causal reasoning to support it.

Firstly, I would question whether the situation in the USA actually supports Tim’s argument. If you look at the last three decades (I hope that time-scale is long enough for Tim), the standard of living of the average worker in the USA was 30% lower in real terms in 2006 (i.e. before the economic crash) than it was under President Jimmy Carter in 1979. Is that because of massive increases in Corporation Tax? I doubt it.

Reducing Corporation Tax increases company profits. So where is the evidence that increases in company profits always benefit the workers first? In my post above I demonstrate that it is the shareholders and the owners of capital who have the first call on any increase on profitability, not the workers.

There is, after all, the Iron Law of Wages: this states that wages always tend to subsistence level because competition between workers for the available jobs usually drives down wages. The only exceptions to this rule occur when labour is in short supply. That can be when there is full employment, or when the jobs concerned require specialist skills that are in short supply, or where professional bodies or trades unions can limit the number of new entrants into that sector of the job market. Corporate Tax just doesn’t come into it as far as I can see, or if it does it is of such secondary importance as to be irrelevant.

First comment was rejected for being impolite. I’ll try again:

“If you look at the last three decades (I hope that time-scale is long enough for Tim), the standard of living of the average worker in the USA was 30% lower in real terms in 2006 (i.e. before the economic crash) than it was under President Jimmy Carter in 1979.”

Could you please explain that? By what standards are you saying that “standard of living of the average worker” has declined over the past 30 years?

I’m willing to believe that the relative standard of living has declined, but not that the absolute standard has. So, care to show where you got this idea from?

@Tim Worstall

Tim, the statistic (perhaps I should use the term very loosely here as it was imprecisely defined anyway) quoted was one I heard on a prominent current affairs programme on TV just before the 2008 US election. So perhaps it was a bit unfair to quote it without putting it into context, or knowing exactly what measure of income it actually referred to was.

The general gist of the quote was, as far as I can remember it, that most average Americans were significantly worse off now than they were in 1979. The main reason offered was the loss of manufacturing jobs, that were then replaced by lower paid, less unionised, and less secure jobs in the service sector. It was not clear, though, whether this statistic referred to gross individual wages, household income, or disposable income.

The actual statistics that are precisely defined, though, are these. Over pretty much that same 30-year time scale median household income has risen only 10% in real terms (from about $46k to $50k). This equates to an average rise of only 0.3% per year. Yet at the same time the number of women in the workforce has increased dramatically. So some of the increase in household income could be driven by the increase in the number of workers in each household, and not by wages, although there is some debate here because the number of single adult households has also increased.

Then there are also the effects of increasing house prices and healthcare costs over the same period to consider. It is therefore not difficult to see (at least for me) why most Americans probably feel poorer now than thirty years ago.

@Cantab83

Many thanks for doing this

It is widely known and widely reported that the US middle class are becoming worse off, and the uncertainty and cost the market exposes them to is a major part of this

Tim will deny the relevance of what you say, of course: he will argue they are absolutely better off and so who cares that the relative gap between them and the elite that exploit them and to which they can increasingly never hope to b a part is growing?

Well I do. Because well being is not measured just in cash. It’s also a heavily relative thing

But that’s an issue that by-passes some

Richard

“The main reason offered was the loss of manufacturing jobs, that were then replaced by lower paid, less unionised, and less secure jobs in the service sector.”

I’m deeply unconvinced that manufacturing jobs pay more than service jobs: isn’t one of the points of this site that jobs in banking and finance are overpaid? Exactly the sorts of jobs that have replaced manufacturing?

Snark aside, a sift through the Bureau of Labor’s site will also show the same thing. Services are not lower paid than manufacturing.

As to median household income, you do really need to adjust for the fact that median household size has been decreasing in the US, just as it has everywhere else.

Just as an example (these aren’t the real numbers) If the average household in 1980 was 4 people and the average is now 3 then only genlty rising household incomes is a sign of very strongly rising standards of living.

And no, the US statistics on household income do not adjust for the changing size of households. We in the UK (in fact, just about everyone except the US) do. It’s a known failure of US poverty and income statistics.

Sorry, no cigar.

@Tim Worstall

Is there no abuse of ordinary people in pursuit of higher returns to capital that you will not deny Tim even in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary – none of which you refute?

And if there no logic that passes you by, such as the fact that the cost of living in smaller households is higher than in larger ones due to economies of scale and that the situation may therefore be worse in reality than the data suggests?

Your partisan nature, selective use of your intellect and contempt for ordinary people is staggering.

Richard

@Tim Worstall

Is Tim arguing that most service sector jobs are in investment banking? Or is he arguing that all service sector jobs are better paid than skilled engineering jobs?

I would love to see the evidence that those workers losing their jobs in the US car industry in the midwest are going on to work for Goldman Sachs. The fact is they are more likely to end up working for Starbucks, although I suppose even Goldman Sachs needs cleaners.

Sadly for Tim and his argument with regard to changes in the size of US households, the trend in median household income is replicated in that for individual income. For male workers the median income in real terms was unchanged from 1970 to 1990. For women it only rose in the late 1980s.

From 1970 to 2004 male median earnings only rose 8%, or 0.25% per year in real terms.

Then there is this interesting statistic regarding the ratio of average wages to the median wage.

Official figures from the US Government show that in the US the ratio of median wages to mean wages has dropped from 72% in 1990 to 67% in 2008. Or put another way, in 1990 the mean was 39% more than the median, and now it is virtually 50% more. That is a relative rise in inequality of 11%. This may seem like a small change, but given the nature of the two statistics it is actually pretty big. It would be interesting to know what the ratio was in 1978 or 1970.

By the way Richard, on the subject of wealth inequality, have you done any analysis of Vince Cable’s Mansion Tax? I have recently questioned why Labour is so reluctant to investigate this as a source of new tax to fund our structural budget deficit. Do you have any figures that could help out? A breakdown of house prices by their number or frequency would be useful. The US government publishes a similar breakdown of US wages by earnings band and frequency. Does the UK government or HMRC produce anything similar?

“Sadly for Tim and his argument with regard to changes in the size of US households, the trend in median household income is replicated in that for individual income.”

I do hope this gets through moderation as yesterday’s clarification did not.

You have to be very careful indeed using the US statistics. They are not calculated on the same basis as those for other countries.

For example, those US income figures are “total money income”. This leads to two distortions against the figures for anywhere else.

1) The vast majority of US efforts to alleviate poverty are not included. Total money income does not include the effects of the tax system. So the EITC (their equivalent of our tax credits) is not included. Nor are food stamps, health care for the poor or housing subisdies: all are benefits in kind and are not included.

2) A significant portion of the income received from working in the US is in the form of again benefits in kind. Notably, health care insurance. To look solely at money income ignores this point: if we look at total compensation then median compensation has been rising strongly over these years.

A good explanation of these changes just for the past decade is here:

http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/09/10/reader-response-falling-incomes/

For the longer period here:

http://mjperry.blogspot.com/2008/08/adjusted-for-household-size-real-income.html

When adjusted for household size, real median income per household member reached an all-time high of $19,546 in 2007 (see bottom chart above), 65.6% higher than the $11,820 income per household member in 1967, and more than 2 times the unadjusted increase per household of 29.6% reported above.

@Cantab83

I think Vince’s proposal was a little simplistic, but appropriate

In the Compass report “In Place of Cuts”, which I co-authored, we said in our list of proposals:

5 Increase the tax payable (higher multipliers)

for houses in Council Tax bands E through H

(while awaiting a thorough overhaul of

property valuation and local authority

taxation) raising a further £1.7 billion.

http://clients.squareeye.com/uploads/compass/documents/Compass%20in%20place%20of%20cuts%20WEB.pdf

See also this proposal I made for the TUC

http://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2009/11/15/a-tax-on-empty-houses/

Best regards

Richard

@Tim Worstall

I am simply amazed at your arguments

here you’re saying that because American health care is so staggeringly inefficient and costly and because employers provide the benefit for many employers at enormous and rising cost to both that Americans are better off

No they’re not. Note the first link your refer to says (I read it after writing the above):

“I think it’s fair to add health care to the two explanations I offered in my earlier post: household incomes have failed to rise over the last decade because economic growth has been slow, inequality has increased and health costs have risen.

Measured in a comprehensive way, compensation for the typical family appears to have risen more slowly over the last decade than at most other 10-year periods in the last 60 years — and perhaps more slowly than at any other point in the last 60 years.”

Why doesn;t that worry you?

Richard

The original statements have been:

1) Median household income hasn’t risen very much.

To which the answer is that median household size has fallen so median income per person has risen substantially.

2) Median individual money income seems not to have risen very much.

To which the answer is that median total compensation has.

These are simple corrections about how US statistics are calculated. Not knowing these things will give an inaccurate picture of how incomes and living standards have been changing.

@Tim Worstall

Tim, are you seriously suggesting that if social security payments were added to the official figures, the MEDIAN income would rise? That would mean that some people on or above the new median income level were living partly on welfare, wouldn’t it? If not, then the median level would be completely unaffected by the impact of social security payments.

Now I have always thought of the USA as the ideological home of free-market capitalism. Am I now expected to believe that it actually stands as one of the shining beacons of state interventionism and socialism with over 50% of the population getting government handouts, including some amongst the top 50% of the country’s wealthiest people? Wow!!! Now that is what I call wealth redistribution.

Oh, and even if this were true, it could still only result in larger than reported annual percentage increases in real median incomes if the real value of those benefits (or the number of people getting them) also increased with each passing year faster than wages. So, does this mean the USA is becoming even more socialist with an ever more generous benefits system?

“So, does this mean the USA is becoming even more socialist with an ever more generous benefits system?”

We come again to the fact that US statistics are reported in a different manner from those of other countries.

When the US measures the incomes of those “in poverty ” (ie, those below the poverty line) it measures market incomes plus direct cash transfers.

Everyone else measures poverty after the impact of the tax and benefit systems.

This means that (by the US system of measurement) poverty is overstated in the US. For they do not include in the incomes of the poor such things as the EITC (their version of our tax credits….and yes, we include tax credits when we calculate the incomes of the poor), Section 8 housing vouchers (think housing benefit) Medicaid (health care for the poor) and so on…food stamps is another example.

On the “social security” point, when discussing the US we have to be very careful to distinguish between “social secuirty” and Social Secutiry which is their version of the old age pension and disability benefits. The system as a whole of just that part they call Social Security?

Now, as to whether the US system is becoming more generous, why, yes, it is actually. For starting in the mid 70s there was a bipartisan move to go from direct cash welfare payments (usually known as TANF)to a system based upon benefits in kind and through the tax system: the EITC.

However, given the way that poverty is calculated in the US this doesn’t show up in the poverty rate. For pre mid 70s, most of the things done to alleviate poverty were included when we worked out how many were in poverty.

Now most of the things done to alleviate poverty are not included when we calculate poverty.

To translate this into UK terms, think how different the poverty rate would be if we calculated poverty before tax credits, before housing allowances, before the subsidy to social housing and so on. It would be a very big change from the rates currently reported.

My basic point here is quite simple. There are details of the way that US statistics are calculated which make them not directly comparable to those of other countries. And not directly comparable even over time for the US. And these details are well known in wonkish circles and make some of the comparisons used not really very accurate.

Much of what is done to alleviate poverty (and that amount has indeed been rising in recent decades, there were expansions of the EITC under Reagan, Clinton, Bush II) is not counted when calculating the poverty rate. Median household income is not adjusted for changes in household size. Median household income (and median individual income) is monetary income not total compensation: and a significant part of compensation in the US is in kind (health care insurance) not money.

Unravelling all of those effects isn’t simple. One who has tried is Tom Smeeding through the Luxembourg Income Study numbers. A very interesting result is that total incomes, adjusted for price differences (ie, using PPP etc) for the bottom 10% in the US are around and about the same (to within 1% of total income) as the incomes of the bottom 10% in either Sweden or Finland. The combination of the US welfare system plus the greater wealth of the country added together give the same standard of living as the much more redistributionary Nordic societies.

Which I think is an interesting result really…..