As The Guardian noted yesterday:

Rachel Reeves should refine her fiscal rules to prevent the need for emergency spending cuts, the International Monetary Fund has suggested in its annual review of the UK economy, as it upgraded its forecasts for UK growth this year.

Adding to the clamour from backbench Labour MPs incensed by the government's proposed welfare cuts, the Washington-based organisation said the chancellor should examine ways to avoid having to make short-term savings when there is a downturn in economic forecasts.

Let me explain this.

Reeves' targets relate to balancing events over a five-year period. In other words, events that might, or might not, happen are included in the calculation of what is possible to do now, even though the decision to act now does, of necessity, mean that future events are contingent on current behaviour.

Let me take an obvious example. The government could decide to restore the winter fuel allowance, remove the two-child benefit cap and unfreeze benefits. That is an entirely plausible course of action for it to take. In five years' time, it is almost certain as a result that:

- GDP will be higher, since the payments made will all recycle, almost immediately back into the economy.

- Children will be fitter.

- They will be better prepared for school, and eventually for work.

- There will be more parents available for work.

- There will be reduced demand for other government support services.

In other words, the current decision has a future consequence, but unless you decide those are the consequences of the current action, that current action is not possible, because the current action is dependent on that future consequence.

To put this another way, you have to decide what the multiplier effect of current decisions is when deciding to undertake them. And when deciding on that multiplier effect, you have to decide whether to appraise such impacts narrowly, looking solely at the impact on tax revenues, for example, or more broadly. The broader approach would allow for all the matters I note above, and what consequences they might have.

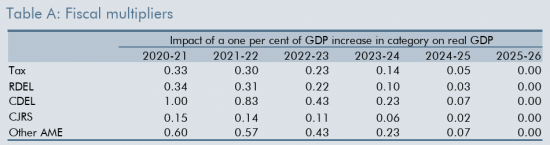

The Treasury is notoriously unwilling to ascribe appropriate multiplier effects to decisions made. Historically, they have always taken very narrow views. They have also used what most people think to be very low multiplier rates. These are those used by the Office for Budget Responsibility, with this data coming from 2020, which is the last time they appeared to refer to this issue in their reports:

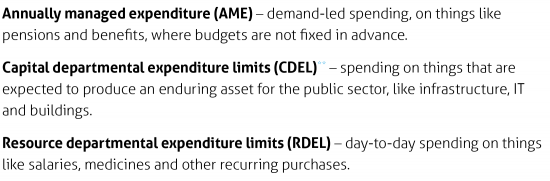

The jargon on the left is translated as follows (care of the Institute of Government's 2024 article on this issue):

In other words, the multipliers used in this area assume that, at most, the cash spent can create a return of £1.90 for every pound spent, over five years.

But isn't that enough to justify this spend, come what may?

So what is Reeves' objection to spending on relieving poverty when it appears that even using these extraordinarily unsophisticated assumptions, doing so pays? I am bemused.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

”In other words, the current decision has a future consequence, but unless you decide those are the consequences of the current action, that current action is not possible, because the current action is dependent on that future consequence.”

That was hard to get my head around! But I agree (I think).

It’s circular, in other words.

Interesting. The idea that increasing benefits has a multiplier effect as high as you suggest is hotly disputed. Fournier and Johansson found in 2017 for example that actually state pensions had a positive multiplier effect on GDP. Cutting subsidies had an even more profound effect on GDP. How do we establish who is right?

Research?

But, I stress, identifying the effect is very hard because of what is called ‘noise’ in the data

I heard some commentator from the Finance Industry on Radio 4 this morning talking utter tosh about how the bond market would be “spooked” if the Fiscal Rules are changed, and there would be dire consequences. As usual the interviewer let him get away with it. As you’ve said so many times, the real issue is political will and ideological framing. If the UK government chooses not to spend more on social welfare, it is not because the bond market prevents it – but because it is choosing not to. And that can really only be to promote an ideological position favouring small government and reduced public spending. All this from a Labour Chancellor. I suppose I should have got accustomed to it by now, but somehow it still beggars belief.

Richard, what do you reckon are the actual multiplier effects?

Higher

I have not done the research to suggest what they are.

Has anyone else?

Might the Chancellor and the Treasury be avoiding, or over minimising, a lateral, but valid, form of double entry book-keeping?

I am not sure I follow your question.

I think the answer is staring us in the face Richard

that is; That Reeves and those around her are abject idots.

Full stop.

While the original concept, and ideals, of a Labour Party was much needed and admired, I’m afraid this present Government falls far short of those targets. Indeed it seems to be blinded to what should be its main tasks, and that is to keep the population of the U.K safe and well. On so many fronts it is not only failing, but seems intent on making matters worse for the most vulnerable in our society. While I have never been a Labour voter, even I had some hope they would improve things for the least well off after many years of disastrous Tory rule. Not only am I sorely disappointed by their initial policies, but they seem intent on making matters even worse by continuing down the same cruel path, apparently in an attempt to outdo the even more evil Farage, and his cabal called Reform.

Reeves’s vacillation is entirely driven by perceived electoral prospects, driven by the private office of Starmer. There is nothing new in this. All parties govern on the basis of what is most likely to get them re-elected.

Oh come on Barnie, they surely can’t believe these policies are going to be popular?

Gordon Brown’s opinion piece in the Guardian today “ By delaying its child poverty plan, Labour has a chance to reverse 15 years of inequality” makes a cogent case for what the UK government should focus on to achieve beneficial multiplier effects. Will they?

Let’s hope they take on board the thoughts of an ex-PM and ex-Chancellor who has always had a strong moral compass.

But Brown is completely ignoring the deleterious effects on children in poverty today. No one would say – look Putin is attacking the south coast of England, let’s wait until the budget to decide if we can afford to protect ourselves!

Agreed

The language used by Reeves Starmer and co – almost precludes the possibility of positive dynamic effects of govt spending. ‘Fixing the foundations’ ‘balancing the books’ ‘making sure the sums add up’.

The fact that GDP has grown somewhat above expectations may be to do with the extra public spending last autumn – but they wont say so – ‘all public spending is just a cost’.

BBC obfuscates as usual – they didn’t even clearly say that even the conservative IMF has suggested loosening the fiscal rule.

It must be emotional logic.

Reeves’ cruel paymasters demand she shrink the government, whatever, and allow them free rein as Neoliberal Overlords.

Multiplier effects seem to be hard to estimate. Often they seem to be significantly underestimated. After the grand financial crash multiplier effects were estimated at less than one. This was, in part, rationale for austerity. It makes sense (if you believe the multipliers). With multipliers less than one government spending of £1 results in less than £1 growth in GDP (that’s the definition). So better for the government not to spend and let the private sector spend and create more growth. Hence austerity driven growth. That’s the neoliberal argument.

But austerity was wrong. It was a failure. It damaged the economy. Even the IMF, that bastion of left wing socialist thinking, eventually had to admit their estimate of multipliers was wrong and that they were significantly above one.

With a multiplier above one it makes sense for the government to spend. If, as a private individual, you knew your pay would increase the more you spent, you would spend. Likewise the government should spend.

But the problem is estimating fiscal multipliers. They are not independent of spending. Spend too much and the multiplier will decrease. So what to do?

In the past growth has been my higher, 3, 4, 5% rather than the pitiful 1.2% currently estimated for the UK. To me the sensible thing to do, in the absence of reliable estimates of multipliers, is to judiciously increase spending in areas where it would clearly have a benefit (and there’s a long list of these). Then see the effect on the economy. That’s the pragmatic approach.

But this, and previous, governments, seem terrified of spending. They appear to worry that it will “crash” the economy. As Mr Belloc put it, “Always keep ahold of nurse for fear of finding something worse”. What’s needed is a little courage, to spend some more, and a little (un)common sense in where to spend it. That is, I believe, why people voted Labour. But, sadly, we do seem to have a government of timid, incompetent, fools.

Sure Start has been found to have had at least a multiplier effect of 2, but, given they started in 1999 and ended around 2012, it has taken quite a long time to calculate that!

https://www.theguardian.com/education/2025/may/22/sure-start-centres-saved-uk-government-2-for-every-1-spent-study-finds

Sure Start was brilliant, and I believe it had hidden multiplier effects. It was a networking event for parents, bringing people from different socio-economic backgrounds together to exchange advice, support, and clothing. It was the economics of being seen. Of course, it had to go. That sort of benefit can’t be seen on a spreadsheet.

Equally significantly, those estimates suggest a relatively short payback period – less than 2 years.

If something was brought in this August, spending say £10bn/year more under that AME estimate, then by August 2029 (the latest date for the next election) then £40bn would have been spent.

By those estimates, it would raise GDP by £6b x4, £5.7b x3, £4.3b x2 + £2.3b = £52b meaning the GDP to national debt ratio (currently just over 100%) would be improved by such measures within the timescale of parliament.

Those figures also look like an under-estimate when it comes to supporting the poorest, because almost all of the money would be immediately spent domestically, boosting GDP directly by perhaps more like 0.9, and that domestic income may be further recycled before the end of the first year, so it would not surprise me if the impact on GDP was actually greater than 1 in the first year alone.

Unfortunately – but not surprisingly – things get worse by the hour as far a Labour is concerned, Richard. To add to what you say here we can now include the demise of the Nature Friendly Farming Fund – although the little gleam of positive is, not until 2026.

By God, Thatcher (the milk snatcher), must be laughing her socks off down in hell at the fact that Starmer’s Labour are even worse that her governments!

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/may/28/nature-friendly-farming-fund-to-be-slashed-uk-spending-review-defra

Another one is the scaling back of the Biodiversity Net Gain requirements for small-scale building projects. BNG compliance is a genuine cost for small builders, but it is not a disproportionately large one relative to overall development costs. The long-term environmental risks of relaxing these rules are significant, and there are better, more targeted ways to help small-scale builders. So it’s entirely possible to both accelerate small-scale housebuilding and enhance biodiversity. Farage effect again?

“So what is Reeves’ objection to spending on relieving poverty”……..

LINO wants poor people to stay poor – so they can blame them for being poor?

Previous blogs have accused LINO of being heartless/bastards etc – one thing for sure – they are consistent in their hatred for those less fortunate in society.

Stamp, stamp, stamp, the sound of the LINO boot stamping on the faces of the poor.

Ah, the IMF—the globe-trotting accountant who only ever seems to knock on your door when you’re halfway through your overdraft and trying to decide between beans or toast for dinner. This time, however, they’ve popped round with what passes for a gift in international financial diplomacy: a polite note suggesting Rachel Reeves might want to rethink her fiscal rules before she trips over them in a recession.

Translation: “Hi Rachel, we see you’re building a budget strategy on sandcastles. You might want to check the tide chart.”

Now, to the meat of the issue—or lentils, depending on your weekly shop. Reeves’ fiscal rules stretch over five years like a gym membership resolution: full of promise today, probably broken halfway through. But unlike an unused Peloton, austerity has real consequences. Real, hungry, cold consequences.

Let’s get this straight. The government could scrap the two-child benefit cap, thaw out frozen benefits, and bring back the winter fuel allowance like it’s a nostalgic reunion tour. Not only would this help people now, it would—as the article wisely notes—generate economic benefits that ripple through the system like a well-aimed pebble in a calm lake. Children healthier, parents freer to work, less pressure on public services. You know, a functioning society.

Yet the Treasury continues to treat economic multipliers like they’re mythical creatures—too generous to be real. Even their own (frankly miserly) assumptions say that for every pound spent, you can get up to £1.90 back over five years. That’s better than most stock tips, and certainly better than relying on trickle-down economics, which at this point is just a polite term for economic incontinence.

So why isn’t Reeves grabbing this opportunity like a shopper on Black Friday? Is it fear of being seen as “fiscally irresponsible”? Is it the ghosts of Chancellors past whispering “deficit!” like a budgetary Macbeth? Or is it just that peculiar Westminster tradition of mistaking prudence for paralysis?

The truth is, poverty is expensive. Cutting welfare doesn’t save money—it just shifts the bill to NHS waiting rooms, food banks, and exhausted teachers. Reeves has an opportunity here to be bold, to reframe spending not as a cost but an investment. After all, the IMF—even the IMF!—is giving her a nudge.

So come on, Rachel. Be the Chancellor who finally figures out that you can’t cut your way to prosperity any more than you can diet your way to a free lunch. Let’s invest in people—and not just in spreadsheets.

Thanks, and see tomorrow’s video.

I’ve been searching for a word for Reeves and I got there in the end.

More proof – as if it were needed – that Reeves is basically completely illiterate for the job of Chancellor.`

I mean, this is investment and the return is there. What more is there to say?

Does she want a private credit bubble instead?

What has changed then, since the Tories? Public investment is so under valued and remains so.

The Treasury needs a good clear out.

I don’t think there is any complex thought or analysis behind Reeves’ position – I think she has just drunk too much of the neoliberal Kool-Aid and it has eroded whatever critical faculties she might have had.