The mantra of the late 1990s was that markets always go up in the long run. It was wrong then, and it is wrong now.

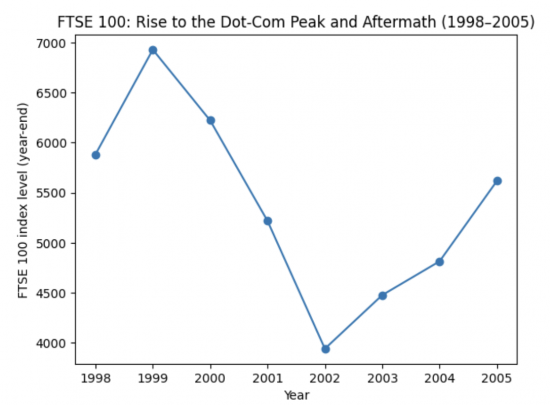

The FTSE 100 reached what was then its all-time high at the very end of 1999, during the height of the dot-com boom. What followed is a useful reminder of how fragile market confidence really is and why markets are a poor guide for economic policy.

The FTSE 100 closed on 30 December 1999 at around 6,930.

At the end of 1998, the index stood at roughly 5,880. In just twelve months, it rose by about 1,050 points, an increase of around 18 per cent.

This was not driven by a transformation in productive capacity, wages, or public investment. It was driven by:

- Speculative optimism.

- Easy credit.

- The belief that technology stocks had abolished risk, and

- The widespread assumption that markets were efficient and self-correcting.

None of those claims turned out to be true.

From the December 1999 peak, the FTSE 100 entered a prolonged decline.

By March 2003, the index had fallen to around 3,300.

That represents:

- A fall of around 3,600 points, and

- A loss of just over 50 per cent of market value from the peak.

This was not a brief correction. It was a grinding, multi-year collapse that wiped out paper wealth, pension values, and investor confidence. And crucially, it took more than a decade for the FTSE 100 to convincingly exceed its 1999 level again.

The chart noted above tracks the FTSE 100 from 1998 to 2005, using year-end levels. There are three very clear phases:

- The sharp rise into the 1999 peak,

- The steep collapse between 2000 and 2002, and

- The slow, hesitant recovery that followed.

Even by the end of 2005, the index was still well below its 1999 high.

This matters because it exposes some fundamental myths:

- First, markets are not reliable long-term allocators of capital. They swing between euphoria and panic, amplifying risk rather than managing it.

- Second, pension security cannot sensibly be built on the assumption that equity markets will always deliver steady growth. Millions of people retiring in the early 2000s discovered this the hard way, but as a society, we have still not learned the lesson, although business has, by closing defined benefit pension schemes and passing the risk onto employees.

- Third, governments that tie fiscal policy to “market confidence” are surrendering economic management to a system that repeatedly proves itself unstable.

- And finally, growth in asset prices is not the same thing as economic progress. The late-1990s boom left little lasting benefit for productivity, resilience, or social well-being, but its collapse imposed very real costs.

The lesson is simple. Markets are a tool, not a guide. When we mistake speculative price movements for economic success, we repeat the same errors again and again. And that is what we are doing now.

Tickets are now on sale for the Funding the Future live event in Cambridge on 28 February. Tickets and details are available here.

Comments

When commenting, please take note of this blog's comment policy, which is available here. Contravening this policy will result in comments being deleted before or after initial publication at the editor's sole discretion and without explanation being required or offered.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

As per – I agree. Looking @ the market (European – there is nowt in the UK) there is little that appeals – high PEs & a large number of (optimistic?) assumptions.

Big changes next year – Russia and the war (if Russia goes pop that will have impacts), China and Taiwan (if I was the Chinese I would “play nice & pretty please” – but they won’t), Trump (increasingly showing himself to be insane). & lastly an increasingly restive population in Europe. How will this impact markets? dunno, which is why for the most part I have departed them.

We ‘know’ a crash is coming, but we don’t know when. My worry is that any significant ‘correction’ will simply obliterate hundreds of thousands of ageing people who use “flexi-access drawdown” in dealing with their defined contribution pension pots in isolation and not in conjunction with, say, annuity income streams.

They will find out all about ‘sequence of returns risk’ and the lack of ‘mortality cross-subsidy’. And no-one can be blamed but themselves.

They will also need to mentally adjust their ‘portfolio returns’ for inflation, which very few do. Having been promised the earth by the investment firms and advisers, they might well end up with dust. Things can be done, but time is tight.

Much to agree with

I’m not sure that I agree with “And no-one can be blamed but themselves”…..if I employ a plumber or an electrician I don’t expect to be adopting the risk for the work that they carry out or be second guessing whether they are working in my best interests.

To hide behind ‘the value of your investment may go down and you may not get back what you put in’ seems vastly inadequate, it might just as well read ‘you’re on your own mate’!

If the ‘product sale’ was properly documented and the assessment of risk was matched to the recommended investment and if the client was uninterested in annuity income (which can be a perfectly valid choice) then a drawdown plan may well have been deemed suitable. However, if the markets take a tumble, and if the client understood this can happen (most do), then that is hard luck as they assumed the risks and costs of being in drawdown personally.

I do have clients that use drawdown successfully, but rarely in isolation – they have other pensions, etc., and a blended mix of retirement income streams is what should be targeted.

Interestingly, over the last few years the problematic drawdown cases that I have subsequently been asked about were not arranged by IFAs, but from ‘direct to consumer’ firms that provide ‘information’ and not regulated advice.

The small print doesn’t do anything for those of us with a little row of workplace pension pots and no means of getting advice. It is a lottery for most people, we don’t have the information, advice or options.

Saying buyer beware is unkind and problematic when the system is based so much on stock markets. Until Richard posted a piece the other day, I had no idea that I could ask for a pension to be held in cash. I had a small pot I took out and put in a bank account as the return after fees was under 1.7% for the previous financial year. So it is no longer a pension.

Anne, any non final-salary pension can be held in cash, and that’s really easy to do with virtually all pension providers. You can do a fund ‘switch’ usually free of charge. Cash is an apt asset to hold in the few years before taking your benefits from the various pots or you might even merge them all together which makes day-to-day administration easier (and, for some, this will be helpful for executors after April 2027 when unused pots can form part of an estate’s value for IHT purposes). There would only be a small ‘cost to change’, and this would be paid on an agreed basis from the pension fund. Many IFAs will look this – we are not all money grabbers on the make!

To be clear, this isn’t advice, just information.

Thanks Mark

I moved into the area of North West Derbyshire where I live now in 2000.

All I can say 25 years later is that everything that has made this lovely place harder to live in is to do with markets – the housing market, markets for food, raw materials, fuel – everything. But the there has also been a rolling back of the state as well which has not helped at all and austerity has worsened this.

This is no way to run modern life at all. The only way that this is perpetuated is through corruption and nothing else.

As we know, money does not have a constant value in terms of purchasing power. Although this is a given for anyone involved in finance, the person on the Clapham bus probably doesn’t think about it. The FTSE index can either be nominal or inflation adjusted. I cannot see on the chart any reference to inflation adjustment. Excuse me if I have missed something in the text, but I read it twice.

There is none: it refers to the index