Yesterday's poll on the household analogy produced some pretty clear results.

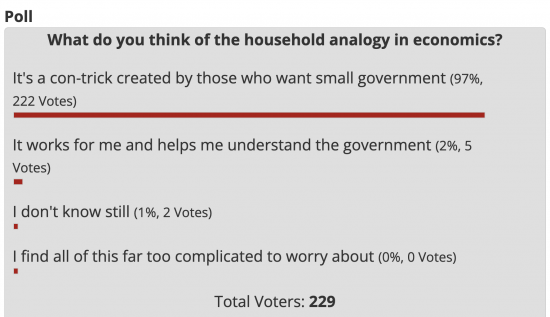

This was the voting on this blog:

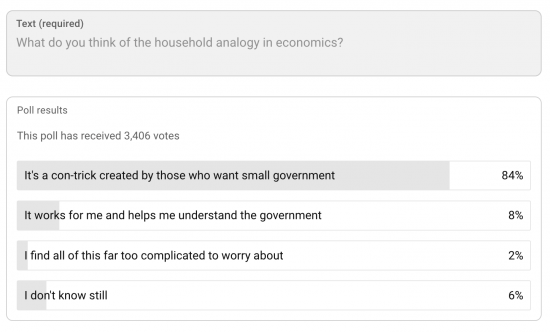

And this was the result on YouTube:

It seems that the argument against this nonsense works pretty well when people take the time to engage and think about it.

So, the question is, how do we get more people to engage with it? I wish I knew the answer to that.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

What we do is equip people with the arguments and examples and stories they can use to persuade others, so that whenever somebody says (for example) ‘the government has no money…’ people have ready, convincing responses – whether it’s in their families, friends, communities, or on social media, or (for a few) other media.

We should certainly be writing to MP’s and complaining to the media about their unthinking reliance on falsehoods. But we really do need people who are likely to be in a position of getting media coverage and have a concrete interest in promoting the truth – which means you can count out pretty much all the mainstream political parties.

But it is in the interest of the unions, and especially the Public Sector Unions, to call out the ‘household’ analogy on the basis of solid argument which is as widely shared as possible by their memberships. It’s what every resident doctor, nurse, paramedic, teacher, lecturer, railway worker, as well as every environmental campaigner, needs to know.

Much to agree with, but I also know that getting these messages into the media is very hard, as my own experience proves. It is much easier to get on the media if you talk the nonsense that the IEA promote than it is if you talk about economic justice, or simply the truth.

There is a weird cognitive dissonance at work. Most people if directly challenged will agree that the state is not like a household, for all the good reasons you could give.

But then they will immediately go back to talking about taxpayers money and fiscal rules and balancing the books and paying down the national debt so we don’t pass on an intolerable burden to our children.

Richard, these points are absolutely correct.

I’m wondering if you could actually do a post using the disconnect Andrew has raised here?

I could, but right now I do not know how.

I suppose the central problem is around belief systems. Identifying what it is that makes us hold on to the mistaken belief even when we see that the evidence shows us it’s wrong.

You are in my video production list, Geoff. I should warn you, there are over 50 videos on the list right now, so I can’t promise when this will happen, but I will most definitely think about it.

Thanks Richard.

Perhaps Edward de Bono and thinking around heuristics?

You mean on how to create alternatives?

His ideas about different ways of looking at things to generate creative solutions. And how we are prevented, and prevent ourselves, from thinking differently ‘. . . being right all the time acquires a huge importance in education, and there is this terror of being wrong. . . . The ego is so tied to being right that . . . you are reluctant to accept that you are ever wrong, because you are defending not the idea but your self-esteem. . . . this terror of being wrong means that people have enormous difficulties in changing ideas.’

(Po: Beyond Yes and No.)

Andrew- reading the comments on Youtube made me realise that, although people seem to have a sense that the orthodox narrative on Govt finance is a bit fishy, there are two very deeply-ingrained ideas. It’s understandable, but frustrating, that people think that “balancing the books” is important for Govts, because of their long and deep experience of managing their own budgets. People still equate “financial prudence” with virtue, and “spending” with “spendthrift”. They have little concept of the Multiplier effect.

The other ingrained dogma is the “spending causes inflation/hyperinflation” trope. The bogeymen of ill-understood Weimar and Zimbabwe still have a huge hold on the public imagination.

And how do you suggest those tropes are tackled?

Somebody needs to throw a brick through the Overton Window!

I can’t think how you could do it, but it would be interesting to find out how many people formed their opinion primarily from seeing/reading your post. If the majority already felt that way, then it is only (!) the msm and politicians who need convincing.

True..

Not for publication as it’s a bit to one side of this discussion, but I think you might be amused.

Waiting in a long queue at a pop-up wet fish counter this morning. In response to a comment, I attempted to explain to the lady in front that paying benefits was a good thing, and tried to explain trickle-up rather than trickle-down effects. The most I can say is that she was silenced. Probably just as well or she might have asked more difficult questions!

Thank you for this blog Richard!

M

Just making people think is the precursor to change, so that must’ve been interesting in itself. Thanks for telling me.

We’ve identified the MSM as the barrier to understanding, perhaps the only one. They attack anyone they perceive as to the left of ultra Conservative ideology, even tories who try to be reasonable. So, they will carry on attacking everyone except Reform. They (Reform) will be supported until they inevitably fail, only to be superceded by something further to the right. They do not give a jot as to what is actually true or not, along as it ideologically correct to them.

Behind the MSM stands wealth and all it stands for, with no regard for the wellbeing of other citizens.

Plenty of people are fighting this, including this blog.

We all ‘feel’ in our bones that something will happen to change the status quo, but we don’t know what that something will be.

It goes back to being brainwashed by school church parents and the BBC from birth.

When humans are fed with stories and ideas for years it takes a big light bulb moment or massive persuasion to convince our brains that there were (or still are) big faults in said stories and ideas.

It also helps to be a deep thinker with an open mind and not everyone is.

Philosopher Harry Frankfurt’s essay (1986) “On Bullshit” and later monograph of the same title (2005) explores the nature of bullshit and how it differs from lying – in that it aims to be persuasive and to give control, not to be truthful. Relevant here for how the “household analogy” is perpetuating “bullshitting”. It’s difficult to challenge as being incorrect, as it is not concerned with being correct!

Here’s a summary from Opera’s Aria AI –

“Here are the key points:

Distinction from Lying: Frankfurt argues that bullshitting is distinct from lying. While a liar is aware of the truth and deliberately misrepresents it, a bullshitter is indifferent to the truth. Their primary concern is the effectiveness of their communication for their own purposes.

Nature of Bullshit: The essay suggests that bullshit is more dangerous than lying because it undermines the very concept of truth. Bullshitters do not care about the truth, which can lead to a general erosion of trust in communication.

Cultural Relevance: Frankfurt’s insights are particularly relevant in today’s world, where misinformation and fake news proliferate. He highlights how the prevalence of bullshit can distort public discourse and affect societal values.

Philosophical Implications: The essay invites readers to reflect on the importance of truth in communication and the ethical responsibilities that come with it.

Overall, Frankfurt’s work serves as a critical examination of how language can be manipulated and the implications this has for society. It’s a thought-provoking read that encourages deeper consideration of our communication practices!”

The distinction is a good one.

People still clinging from the house analogy and the “taxpayers’ money” because these concepts include some sense of justice and prudence.

If gov can print money for free and give it away to its favourite voters then anything goes, I do not have to work hard to make money, I have to lobby government. This happens to an extent already with the different pressure groups (ie pensioners, ethanol farmers, unions). If I have connections with the gov then money scarcity rules do not apply to me.

I know tax is to control inflation, but who is responsible for inflation and why? Justice for some people also means pointing the finger to the culprit.

Successful (that make good profits) people feel that they are tax penalized for their success. This is a fundamental problem with money driven society. Successful people (businesses) get benefit from the progressive taxation, they just do not experience it as vividly as the direct taxation. When immediate experience is different from long term effects people have issues (heroin analogy).

People on benefits are seen as getting something undeservingly. This is because benefits system is not robust but patchwork, not because welfare state is seen as wrong per se.

Some people (working class by “mistake”) like inequality and they want the inequality to exist when they will fix the “mistake”.

An example I give is crime…middle class (or society in general) will have either to pay for benefits/community centres/proper rehab, or will have to pay for more alarms, higher fences, more police, more prisons. Some people I see feel that the first option is unfair and prefer to give their money to the second option. Same for universal health and many aspects of the organised society and welfare state. The reason behind this is as well a household analogy, projecting interpersonal justice and individual virtue to the society (masses / system).

These people are not always obnoxious, sometimes they are very charitable, but being charitable is part of the problem because they try to solve a systemic problem with individualistic virtue patches. 1,000,000 virtuous individuals can form an evil society, from the individuals to the society it is not a sum.

The problem is so complex that Richard is very right to point out that we need a different kind of values (politics) altogether, it is not something that is fixed with tweaks.