There has been discussion on pension fund management here over the last day or two.

My suggestions when making my comments were threefold:

- Risk is not the same as uncertainty.

- Uncertainty describes situations where outcomes are inherently unknowable, and these exist in defined benefit pension schemes, even in run-off.

- The realities of law, trust relationships and fiduciary duty have to be taken into account.

To put it another way:

- Risk refers to situations where outcomes can be assigned probabilities based on known distributions.

-

Uncertainty exists in scenarios where outcomes are not quantifiable due to a lack of reliable data or unprecedented events.

I really do not think this should be so hard to understand, but it appears that it is, even though this is very basic stuff, and the intellectual foundation of a lot of what Keynes did to upset neoclassical economics.

My contention is that there is uncertainty in the management of even closed, defined benefit pension funds. Again, why this is so hard to comprehend is very hard to work out.

What really scares me is how many of the claims being made by those seeking to criticise me are so profoundly reminiscent of the misplaced beliefs commonplace in the City of London before the global financial crisis of 2008 erupted.

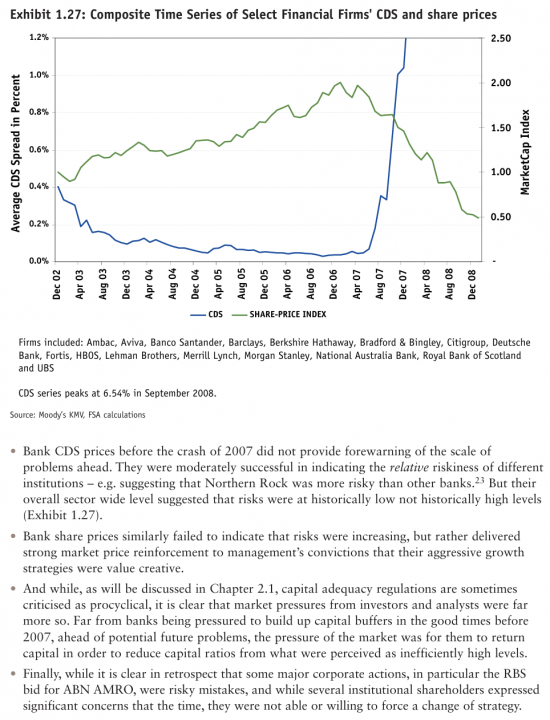

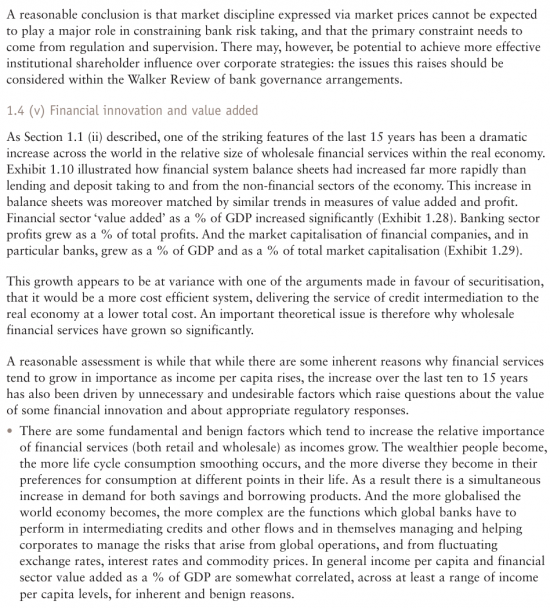

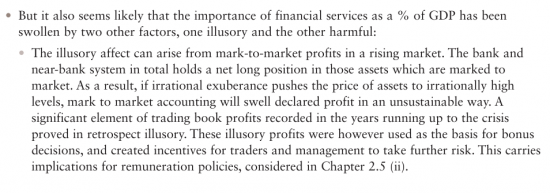

As was clear after the event, almost all the assumptions that markets made before that crash were inappropriate. The errors made were summarised in March 2009 in a report prepared by Adair Turner (Lord Turner), who was then working with the Financial Services Authority.

I have cited section 1.4 of his report to highlight this issue when teaching in the past, because I think it is such a good summary of what went wrong.

On Saturday night, when writing this, I used Chat GPT to summarise the key points, as follows:

A summary of Adair Turner's key discussion on the difference between risk and uncertainty in The Turner Review, particularly from section 1.4(iii): Misplaced reliance on sophisticated maths:

Turner's Key Points on Risk vs. Uncertainty

Distinction Between Risk and Uncertainty

-

Turner highlights a foundational critique of financial risk modelling: it treats the future as though it were governed by probabilistically predictable patterns derived from the past.

-

He argues that this approach is methodologically flawed when applied to financial markets, which are influenced by social and economic behaviour, not physical laws.

Risk refers to situations where the probability distribution of outcomes is known and can be mathematically modeled (e.g. dice rolls, insurance tables).

Uncertainty (or “Knightian uncertainty”) refers to situations where the distribution of possible outcomes is inherently unknowable or non-repeatable — especially relevant in finance where market behaviors are influenced by human psychology, feedback loops, and system-wide interactions.

Flaws in Financial Models

Turner critiques models such as Value at Risk (VaR) for assuming:

-

Past patterns can reliably forecast future events.

-

Events are independent and normally distributed.

-

Risks are largely idiosyncratic (firm-specific) rather than systemic.

In reality:

-

Distributions in markets may have fat tails — i.e. extreme events are more likely than predicted.

-

Risks are often systemic, with one institution's behaviour affecting others.

-

This mischaracterisation meant that models underestimated real-world risks just before the crisis struck.

Knightian Uncertainty and Policy Implications

-

Turner refers to Frank Knight's 1921 distinction between risk and uncertainty to suggest that not all financial risk can be reduced to numbers.

-

He asserts that the 2007–08 financial crisis exposed this fallacy: regulators and institutions faced not risk, but uncertainty.

-

Because of this, no model or regulation can fully eliminate financial crises.

-

There is a need for:

-

A macro-prudential regulatory approach (not just firm-level risk models).

-

A backstop mechanism (e.g., government intervention or “risk socialisation”) for times when uncertainty overwhelms the system.

-

Supporting Sources Turner Mentions:

-

Frank Knight – Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit (1921)

-

Adair Turner's own speech – Uncertainty and Risk: Reflections on a Turbulent Year (Cass Business School, 2008)

-

Benoit Mandelbrot – The Misbehaviour of Markets

-

Nassim Taleb – The Black Swan

✅ Conclusion:

Turner's core argument is that the financial crisis revealed the limits of treating uncertainty as risk. Future financial oversight must recognise this and rely less on mathematical models and more on judgment, resilience planning, and systemic safeguards.

In summary, it was the lack of understanding between risk and uncertainty that helped create the 2008 financial crisis, and the same issue is being seen now.

This is so important, I also offer the original section here (and you have to work hard now to find this report on the web). You only need to read this if you are going for a first:

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

I’ve been using ChatGPT myself this morning. I had an idea but I’m not an expert in pensions, so turned to AI. Here’s the outcome. The ideas about hybrid solutions at the end might be worth more exploration.

You said:

Pension funds are always a contentious issue in the UK, with concerns about opacity and sometimes dishonesty in the way they are managed. How viable do you think it would be if all workers received a pension paid from from public funds under terms akin to the Civil Service Pension scheme, based either on length of service and final salary, or length of service and average salary, with contributions (which would really be a form of tax) set at levels similar to a reputable Defined Benefit scheme in the public sector? Would this be affordable from the public sector point of view, and what would the effect be on the private investment sector?

ChatGPT said:

Your question gets to the heart of the political economy of pensions — a system that sits at the intersection of fiscal policy, social justice, and the architecture of capital markets. Let’s unpack your proposal step by step, focusing on viability, affordability, and wider economic effects.

✅ The Proposal in Brief

You’re essentially suggesting:

A universal public pension system, modeled on Defined Benefit (DB) public sector schemes such as the Civil Service Pension.

Benefits based on length of service and either final or career-average salary (CARE).

Contributions would be made by employers and employees but functionally resemble a dedicated tax.

The state becomes the guarantor of pension benefits, possibly reducing the role of private pension provision.

Affordability: Could the State Fund It?

Key Cost Considerations

Demographics: As with any DB scheme, longevity risk and aging demographics are a core challenge. However, the state already handles this risk via the basic State Pension — expanding it to a full DB structure increases the exposure.

Public Sector Comparisons: Existing public schemes (like the Civil Service Pension) have employer contributions in the region of 20–30% of salary (including notional employer contributions). Replicating this across the private sector would mean a massive increase in effective labour costs.

Transition Costs: Moving from a mix of DB/DC/private/state provision to a state-run DB model would incur heavy transition liabilities, especially in honoring accrued private pensions or unwinding current schemes.

Fiscal Capacity and MMT Lens

If you adopt a Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) lens, the real limit is not financial, but inflationary pressure and resource constraints. The government can always issue currency to meet obligations, but it must:

Manage inflation via taxation and resource allocation.

Ensure productivity and supply can absorb higher spending.

Under this frame, a national DB pension is feasible, but only if the economy has the real capacity (workers, goods, services) to support retirees in the future without driving inflation.

Impact on the Private Investment Sector

Investment Management Industry

A major shrinking of the private pension and asset management sector would be inevitable.

Defined Contribution (DC) schemes, which currently channel savings into private equity, bonds, and other assets, would become obsolete or peripheral.

This could lead to reduced inflows to capital markets, particularly equities and long-duration bonds — potentially lowering asset prices or changing ownership patterns.

Corporate Finance

Large pension funds today are major institutional investors. Removing them could:

Shift ownership and governance away from institutional investors to state-backed entities (or reduce discipline on corporate boards).

Alter the cost of capital — especially for companies that depend on pension fund investment.

Social and Economic Effects

Pros

Security: Reduces old-age poverty and insecurity. A strong DB pension encourages long-term planning and reduces reliance on housing wealth as a retirement fallback.

Equality: Helps level the playing field between public and private sector workers.

Simplicity: A single national scheme is easier to understand and manage, reducing administrative costs and mis-selling scandals.

Cons

Labour market rigidity: Tying pensions to length of service may discourage labour mobility unless designed flexibly (CARE schemes help here).

Intergenerational equity: Younger generations may bear disproportionate costs without corresponding benefits unless the scheme is carefully designed.

Moral hazard: Political pressure could lead to benefit overpromising or underfunding (as happened with many public DB schemes globally).

⚖️ Is It Viable?

Technically: Yes, especially if phased in over time and linked to average earnings (not final salary), and if economic capacity is managed prudently.

Politically: Very challenging. You would need:

Broad consensus to reform pensions as a public good rather than a private savings instrument.

Willingness to confront entrenched interests in the finance industry.

A strong case for trust in government long-term stewardship.

Possible Hybrid Models

If a full state-run DB system seems too radical, intermediate steps could include:

A mandatory public pension top-up (e.g. auto-enrolled into a national CARE scheme).

State-provided guarantees on minimum returns for private DC schemes.

A “public option” pension fund to compete with private providers (similar to Nest, but more generous and DB-based).

Summary

Aspect Assessment

Affordability Technically feasible with real economy constraints in mind; high upfront cost but offset by public good benefits.

Impact on Private Sector Substantial reduction in financial intermediation; disruption to asset management and capital markets.

Equity and Security Strongly improves retirement security and fairness.

Risks Political capture, sustainability pressures, intergenerational tensions.

Overall Viability Viable under certain fiscal and economic conditions, but politically sensitive and disruptive to private finance.

Fascinating, but I think there is one insurmountable issue:

You would need “A strong case for trust in government long-term stewardship.”.

Well, that’e the end of that idea!

You can probably trust a Government more than a private sector scheme to pay what is due, as they don’t have a fund to (mis)manage. Where trust falls over is in their tendency to keep watering the schemes down, so fortieths become sixtieths, final salary becomes average salary, and “contributions” keep edging upwards. So there would need to be some kind of legal framework to stop that. Other countries like Sweden, Canada and the Netherlands apparently have good Government schemes, so might be worth looking at. But I suspect the hybrid ideas might get more traction in the UK if the will was there to at least do something.

I thought one of the most interesting points in ChatGPT’s answer was how dependent the finance industry is on people making their contributions. To listen to those involved in the industry, you’d think it’s the other way round. Contributors need to get into collective bargaining somehow.

Defined Benefit schemes are typically loaded with government bonds during their final years. I’ve no problem with that as long as the defined benefits are covered, but what’s the risk of gilts defaulting.

But you are guessing, aren’t you?

Well, we did once have a state run defined benefit pension scheme – SERPS but the Thatcher Government abolished it

Another perhaps simplistic way of putting it is that it is better to be roughly right than exactly wrong. Economists and the bankers they advise try to convince us that with their all seeing knowledge and expertise and complex models, they can be trusted to be exactly right.

All the evidence points to the opposite. And they choose ignore resilience and redundancy.

Correct, Robin.

And entirely agreed.

The largest risk of a financial crisis is the risk that policy makers won’t adjust fiscal policy in a timely manner,

which is a very high risk indeed!