I noted in a video recently that if the Bank of England was setting interest rates now in accordance with long-term trends, then the real interest rate (i.e. the interest rate less the inflation rate) should be as close to zero as makes no difference.

The suggestion is based on a Bank of England staff working paper by Paul Schmelzing published in 2020. In it, he argued:

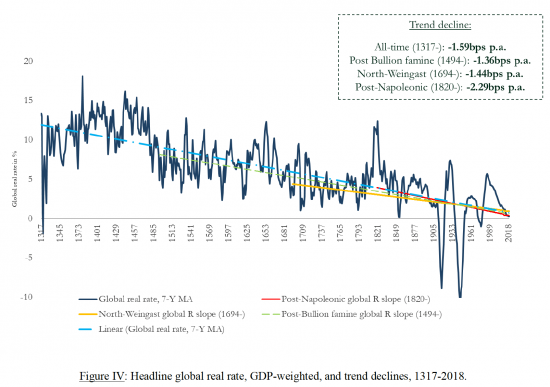

With recourse to archival, printed primary, and secondary sources, this paper reconstructs global real interest rates on an annual basis going back to the 14th century, covering 78% of advanced economy GDP over time. I show that across successive monetary and fiscal regimes, and a variety of asset classes, real interest rates have not been ‘stable', and that since the major monetary upheavals of the late middle ages, a trend decline between 0.6–1.6 basis points per annum has prevailed. A gradual increase in real negative‑yielding rates in advanced economies over the same horizon is identified, despite important temporary reversals such as the 17th Century Crisis. Against their long‑term context, currently depressed sovereign real rates are in fact converging ‘back to historical trend' — a trend that makes narratives about a ‘secular stagnation' environment entirely misleading, and suggests that — irrespective of particular monetary and fiscal responses — real rates could soon enter permanently negative territory.

The most relevant of the charts in the paper is, in my opinion, this one on long-term trends in real interest rates:

As the trend line in that chart shows, we have now reached the point where net real interest rates should be zero, and there is no excuse for them to be anything else. Essentially, the risk in money lending has gone in a system where the return of funds is guaranteed by the central bank. Nothing more than a return that maintains the value if the money is deposited is required in that case. After all, why else are government guarantees on bank deposits provided if it isn't to eliminate risk and so keep rates as low as possible?

So, why is the Bank of England trying to impose rates that are so out of line with long-term trends at present? I am sure Andrew Bailey might respond to requests for explanation written on the back of a £50 note. If you haven't seen one of them for a very long time, guesswork will have to do. My guess is that the reasons why we have rates so out of line are

- Bankers could not look the gift horse of inflation in the mouth without exploiting it.

- The City thinks the world is made up of bankers. This is good for bankers; ergo, they think it is good for everyone.

- The Monetary Policy Committee are indifferent to growth: long ago, they realised that British capitalism is not about creating value but is instead about extracting it from others, and high interest rates are a perfect example of that. In that case, successfully imposing high rates is a smart move in their book.

- The Bank of England is not accountable for its actions by deliberate neopolitical choice.

- There is no one in politics with the guts to stand and say this is wrong, with reasoning attached.

The system is rotten, in other words.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

Turning the equation on its head, might I suggest that we need to ask the question of why do we charge/offer interest and who should pay what?

Clearly especially at the moment the National Debt is a good way of redistributing income upwards, indeed it seems reading Piketty that it always has been, conversely we need to think about how we can offer savers something that maintains the value of at least a portion of their savings.

We can offer long term low or no interest rate credit to people like homebuyers and local authorities but more expensive credit for say buying cars

Let’s say that there is a collective Damascene conversation of the MPC to low interest rates – e.g. 1.5% or 1%. This feeds through to “normal” interest rates – so 2%? 2.5%? What happens to house prices? given that the current UK gov whilst long on rhetoric is short on action wrt house building. Would the low interest rates trigger yet another surge in house prices? I ask this cos it is clear that the gov needs all sorts of policieis in place to take advantage of low interest rates. There are none.

Credit controls are needed Mike.

I have suggested some sort of national ‘Citizens Mortgage’ that would cover all but the most expensive properties.

This would have various checks built into it including a price to earnings ratio.

Clearly banks COULD lend ‘on their own account’ but might have a hard time explaining why and controls might be needed to prevent this

Or (and?) tax on capital gains even on owner-occupied primary/sole residence; and perhaps a higher rate of sales tax (‘stamp duty’).

Some ecological economists have also proposed limits, or at least progressive to punitive taxation, on the per person size of residences.

Try what I suggest in the Taxing Wealth Report

I thought you had made a rare mistake yesterday in saying that the rates had been “monitored for 500 years by the B of E ” when it has only existed for 330 years. But it was a retrospective monitoring. Glad to see the Bank employs historians, They are very useful people!

Thanks for clarifying.

That one was not just for you, but mainly so.

Thank you

“Essentially, the risk in money lending has gone in a system where the return of funds is guaranteed by the central bank.”

This isn’t true is it. You are saying there is no default risk and the rate of interest on all loans made will be identical and the same as the gilt curve. Clearly this is not reality. Very recently Kemble, Harland & Wolff & Typhoo Tea are among a long list of companies that have defaulted on their debt and this is very much part of a very long list.

I was talking about cash deposits

If you are going to comment here please read what I have said first.

I have no problem with the idea that real interest rates should be much lower. However, appealing to a 500 year trend as a reason doesn’t make sense to me.

I think the recent (well recent on a 500 year view) trend is driven by aging populations. With a young population real rates must be positive to reward consumption postponed; as the population ages lack of credit demand would suggest negative real rates. Persistently negative real rates can deliver asset price bubbles but demography trumps everything – just look at Japan where a perfectly decent house is available in rural Japan for about £30,000 despite rock-bottom rates “forever”.

Longer term, it’s “all change” in 1971 as the dollar came of the gold standard; prior to that any interest rate had a credit component, after, it is a (credit) risk free rate. Indeed, one could say that credit risk is replaced by inflation (or uncertainty over future inflation) risk in the data. Personally, I think falling rates (1400 onwards) are all about rising confidence in the “state” and its ability to repay; a loan to Queen Victoria was a safer bet than lending to a Plantagenet king.

So, yes, rates should be lower but the 600 year chart is just a fascinating story.

They make sense if the trend fits the facts that prevail now

I am suggesting that is the case.

Surely it depends on whether you think it is right for interest rates to be used as an economic tool – while the economy is very slow to respond to rate changes it isn’t clear there are enough alternative levers.

If interest rates are to be used in this way then you would have to accept that base rates can stray a little up or down from the inflation rate. And also reflect the way published inflation is backward looking, the basis should surely be the best estimate of current inflation which may be higher or lower depending on trends.

Nevertheless, is there any good argument for current base rates being higher than around 3%?

[Note: I am relabelling myself “Jonathan B” after someone else with the first name Jonathan has recently been posting here – I am sure neither of us would want to have the other’s political views attributed to them].

As a recently retired person who previously had low income (charity sector) and no capital outside of my home, I used to wish for higher interest rates once my lump sum plopped into my account.

But as my capital is for rainy day use (future care needs, repairs & replacements & paying for things like health care when NHS disappears) and my current income exceeds my needs, all I really need from my savings is protection against inflation, ie: zero real interest rates.

The main “real terms” unavoidable changes at present in my personal finances as a pensioner, are the gradual increase in income tax, due to frozen personal allowances and the above-inflation increases in council tax and water rates.

Car & home insurance & food are also going up faster than inflation.

I have 2 v small pensions due to kick in 3 years to help inflation-proof my income.

Given the link between interest rates and housing costs for many (not me), ie: mortgages and rents, and the effect they have on increasing costs for SMEs, there seems to be every reason to want them down to real rates of zero.

(Unless you are a v greedy, v wealthy person with no moral compass, and wearing blinkers and headphones.)

You mention capital controls, which I vaguely remember from my youth. Please add them to the topic list, meanwhile, I will do some revision!

This is very slightly off topic but still to do with money the BoE etc.

The ex-MP Steve Baker has posted something. It is hard not to bust out laughing at what he says & the way he deforms reality, sometimes by omission. (example: “Whenever a bank makes a loan, it simultaneously creates a matching deposit in the borrower’s bank account, thereby creating new money.”……….& when the loan is repaid – what then?)

https://fightingforafreefuture.substack.com/p/bitcoin-gold-and-the-bank-of-england

Baker echos the bonkers stuff coming out of the USA and the Trumpists (gold bitcoin etc). Baker is supposed to be bright, perhaps he is, but he has never been able to think for himself.

Might it be that the Bank of England is wrongly labelled?

Might a more accurate label be the Bank for Rentiers?

🙂

I have nothing against ordinary high-street bankers – the likes of Captain Mainwaring and Sergeant Wilson (although I do think that high street banking and the basic processes that support it, such as payment systems, should be provided by the state as should any other essential infrastructure service), but providers of corporate casinos, private equity mongers, asset strippers etc. are just economic parasites and for them the appropriate collective noun is “a wunch”.