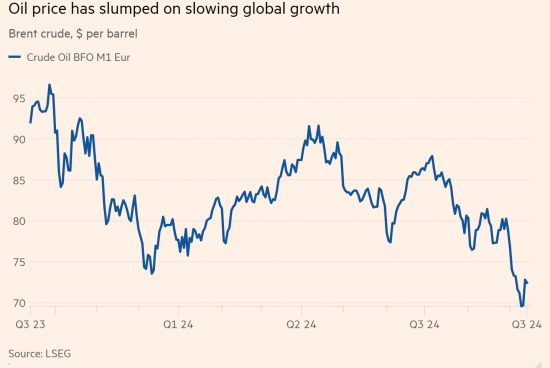

The FT has noted the steadily falling price of oil in an article published this morning:

There are three issues in play.

The first is that demand for oil is falling. Electric cars and high speed rail are tipping the balance against it.

Second, new supplies are more than capable of meeting any growth in demand now: there is, in effect, excess oil capacity in the world now.

Third, this means OPEC is losing its control of oil pricing.

What does this mean? That seems to be the important question.

First, it means the chance of an inflation recurrence is much diminished. The Bank of England should take note.

Second, it says action to tackle climate change is beginning to work. It has a massively long way to go, so let's not celebrate right now, but there is some progress.

Third, let's note the role of China in this. It is leading in electric car technology. Demand for oil in that country is falling.

Fourth, this reduces the incentive for further change with regard to oil consumption. Governments may need to consider whether to tax oil now.

Fifth, global stability might improve slightly, although water is going to be the cause of that stress now, come what may.

What is clear that long established assumptions are no longer valid. At some point the hegemony must break. That is when real change will happen.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

What you are saying about demand already falling is in contrast to what the IEA are saying which is:

Global oil demand will rise less than previously thought this year, led by weakness in China, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said on Thursday, bolstering its view that consumption is heading towards a plateau this decade.

World demand will rise by 900,000 barrels per day, the adviser to industrialised countries said in a monthly report, down 70,000 bpd or 7.2% from its previous forecast, which is at the lower end of the range the industry expects.

There is a wide split in 2024 demand growth forecasts, owing to differences over China and the pace of the energy transition to cleaner fuels.

In other words, demand is technically still rising, even in China, but much more slowly.

Which is what happens at tipping points

Sadly, global growth in oil is still projected up until 2030, and at between 1 and 3.5 % per annum

I suspect that OPEC will simply reduce supply, as they have always done in the past, to keep prices up, as they see fit…

Reportedly, we’re still heavily subsidising oil and gas – £13.6 billion a year, mostly in tax reductions.

The UK ranks 11th out of 11 OECD countries for transparency on fossil fuel funding.

That £13.6bn would tick a lot of boxes for Reeves…..

It is a reminder that in the long term (the term when Keynes, speaking as an economist, said we are all dead); in the longer term technology, not politics drives change. We overestimate the power of politics, and underestimate the power of technology to lead us; and of course the power of money. The two real drivers of our world. We find this very difficult to understand still less accept; because we think as conscious human minds we are responsible for both money and technology as human inventions, and therefore we are in control; but we are not.

“Every step and every movement of the multitude, even in what are termed enlightened ages, are made with equal blindness to the future; and nations stumble upon establishments, which are indeed the result of human action, but not the execution of any human design.” (Adam Ferguson, ‘An Essay on the History of Civil Society’, 1767)

Agreed

Let us hope so, but would it not be truly awful if a war with China was just a proxy war over saving oil?

As of today (17 Sep 2024) Britain’s energy comes from:

34.5% fossil fuels

21.7% renewables

26.5% other sources (nuclear, biomass)

16.9% interconnections (other countries)

Source: National Grid: Live

https://grid.iamkate.com/

It’s worth remembering that we have other energy demands —e.g., transport, industrial processes, non-electrical heating and cooking— in addition to the electricity grid. When these are included, the UK still depends on fossil fuels for more than three quarters of its needs (see, for example: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energy_in_the_United_Kingdom ), although oil now accounts for just under a third of this total.

I always remember being told by someone I valued as a thoughtful individual telling me that what really mattered as a major factor in human well-being was capital investment. Most of Britain’s amateurish politicians appear to have forgotten this needs to be well-balanced between public and private sector investment. Because they’ve allowed themselves to be corrupted they also fail to understand that the state can easily be a powerful funder of such capital investment.

I remember a conversation with a friend at the height of the Iraq war, which was roughly speaking ” Now we see the Oil Wars, wait until we see the Water Wars”.

A very significant component of the conflict in Palestine is control over water resources. And in particular Israeli control over water under the occupied territories. Which is to say that (at least in part) we already have conflict over access to water. As climate change leads to change in rainfall patterns, it will only get worse.

Agreed

This is the entire problem. Its the markets that decide oil and gas prices, not supply and demand. When energy prices, driven by rising oil and gas prices rose in the last quarter of 2021, it was, according to energy experts, driven by the markets essentially wanting to gouge the Asian market on the back of a tiny rise in demand.

In other words, events in Ukraine had bugger all to do with energy prices initially rising. It was simply down to the markets. Yes, fears over gas supply from Russia gave the energy companies an excuse to raise prices further, but that excuse soon fizzled out. Yet prices still kept rising.

As you rightly say, there is more fossil fuel coming out than we can actually use. The USA had a surplus on the back of their traditional sources, fracking is now adding even more. Elsewhere, new technologies mean fields from the middle east, to Russia, Asia and South America are producing a healthy amount of fuels.

So, what’s the answer? Why are prices so high when there’s so much coming out of the ground? As another poster said, cynically limit what’s coming out to keep prices high. Oh, and the markets pushing prices up to what ‘they’ want them to be.

Supply and demand? To hell with that, there’s money to be made.

It’ll be interesting to see if this trend continues – I am specifically thinking about the expected exploitation of Antarctica as the Antarctic Treaty will soon be up for review: I think in 2042 if memory serves. The UK has its claim (of course) to part of the Antarctic territories through its occupancy of the Falkland Islands and claimed soveriegnty of South Georgia & Sandwich Islands focused on the Weddell Sea (and surrounding land) that is estimated to contain around half a trillion barrels of oil as well as potential rare mineral mining sites, a very valuable set of natural resources for any country. The UK, Argentina and Chile have overlapping claims to this area. This oil reserve in the Weddell Sea was evaluated and confirmed by Russia (they have their own claim on Antarctic territory) who some have speculated might decide to get involved with this disputed claim. Demand for oil isn’t likely to affect the serach for minerals but should the 500bn+ barrels of oil no longer appear quite so lucrative – and all operations are extremely difficult (and therefore expensive) in such a hostile environment, the increasing international jockeying and tensions (Argentina and Britain remain very much at odds over this) may well subside as the value of the oil falls. Its probably worth remembering that both the US and Russia are major players in this too.

Another factor which will be starting to play into the longer term demand trends and may be effecting China already, is the fall in birth rates. The countries in the richer energy consuming countries are seeing birth rates , on average fall to about 1.6/1.5 per female. Such a low birth rate (2.1, is the replacement rate) results in a fall in generation size of about 50% in three generations. Put simply fewer people should mean less demand for energy.

China has seen actual falls in population for the last couple of years resulting in a significant fall in working age population. This will also be feeding into energy demand.

I have been arguing that the next tipping point, which very few seem to be looking at is rapid population decline over the next century. It would be very interesting to have your thoughts on how MMT can be used to manage this decline.

By the way I am of the opinion that the decline is a good thing for the sustainability of life on this very fragile world, so policies to increase birth rates are, in my opinion not an option.