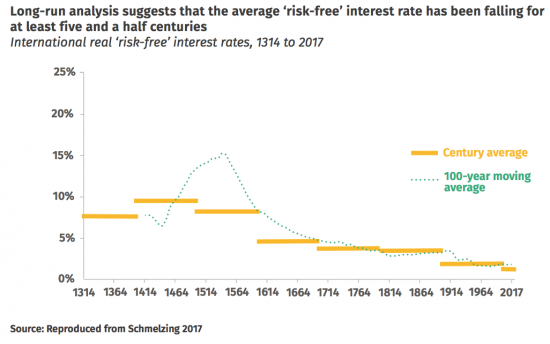

I have used this chart before, and I do so again without apology. It comes from an IPPR report, but that's irrelevant to the use that I'm making of it:

What, I suggest, is that this chart shows something quite staggering. I call it the death of interest. The trend is long-term and inexorable, in my opinion. The simple fact is that the so-called 'risk-free' interest rate is disappearing.

I stress, this does not mean that interest will not be charged in the future, but to understand this it has to be appreciated that the interest rate charged on most loans is made up of two components. One is the cost of money, and since for most banks the cost of money is little different to the 'risk-free' interest rate this charge is tending towards zero over time. That's precisely because, as modern monetary theory explains, there is no cost to creating money and as a consequence there is no cost to lending it, meaning that its price should, in fact, be nothing. That is a fundamental reason why, overall, interest rates remain low now, on average, when compared to long-term norms when different money creation arrangements prevailed.

The second component is not really an interest charge at all: it is a risk premium to cover the chance that the borrower will default upon their loan obligation, and leave the lender with a bad debt. This is, of course, why many loans still carry quite exceptional interest rates when official rates are almost non-existent.

I am not, then, suggesting that we will see the disappearance of interest in the economy: as long as default risk exists there will be interest charges, but that is not the point at issue here. All that disguises is the fact that the real, risk-free, interest rate is tending towards nothing and that means that, in effect, the entire mechanism of monetary policy is now redundant.

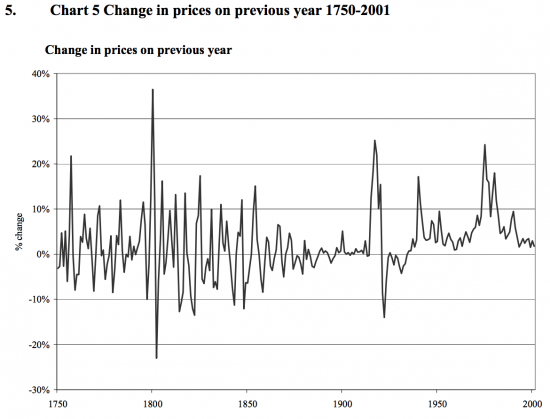

There is another reason for this redundancy: if interest rates decline so does inflationary risk. This is a chart of long-term inflation in the UK, from the House of Commons library:

The risk-free interest rate is declining in the UK and wholly unsurprisingly so too are oscillations in inflation rates, especially if war and the world crashing out of the gold standard and the UK leaving other exchange rate mechanisms (such as the ERM) are taken out of the trend, they being the only real explanation for significant inflation hikes since the 1860s.

I have already suggested today that monetary policy now seems to be a wholly irrelevant mechanism for economic policy control, but so too, I suggest is inflation targeting. The reason is common between two: if interest rates are tending toward zero, and I think they are, then inflation is inevitably going to tend in the same direction, external shocks apart, which can never be corrected by monetary policy.

The time to bury monetarism really has arrived. And in that case the day of the independent central bank is also over.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

I agree that our view of the central bank as a body that sets national interest rates in order to control inflation is now meaningless. Most dramatic shifts in inflation are now driven by international forces, such as oil price movements or currency fluctustions, which are completely unaffected by domestic interest rates.

In addition the Global market place is now so large that old models of capacity constraints no longer apply. If domestic demand for goods or services peaks then suppliers will simply source from around the world. With fully elastic supply, there is no rise in prices, because there is no excess demand. The same applies to wage rates. Workers can no longer drive up salaries since companies can choose to import immigrant workers, automate, or simply outsource work overseas. So we have an elastic Jobs market too.

However we need to take a hard look at how banks can control the flows of finance. Central banks gave akready been doing this on a massive scale with quantitative easing to prop up financial markets. But in a World where the supply of money itself has become highly elastic, the question of who gets access to capital becomes central.

At a nation level given that the cost of capital is mainly down to risk why is the government paying over the odds for private finance of public projects? The government is as clise to zero risk as you can get, yet still pays over the odds.

Meanwhile local communities and deprived minorities are starved if capital for cultural reasons, reinforcing huge inequalities. In the United States 80% if all start-up capital gives to just three states. How much potential is going to waste in our regions because of a centrist approach to lending? There is an overwhelming case, not only for a national investment bank, but also for a new local banking structure designed to fuel investment and innovation.

Investments in green energy provide an ideal entry point, as they are as close to zero risk as you can get in the lending business.

The increase in the yield on short term treasury bonds does not support what you say. This was covered in today’s FT

https://www.ft.com/content/705fdc4e-57b9-11e8-bdb7-f6677d2e1ce8

If you honestly think that rate rises are going to last, I guess that is your right. But I do not agree: the next move will be downward, if anything. And the US increases are deeply detrimental to world well-being and I think that they will also reverse, relatively quickly.

Not necessarily what I think but factually the risk free rate is trending higher.

I am discussing centuries of trend here

And I also question whether you are right: you are seeing differentials due to varying inflation rates

To call bank borrowing risk-free is misleading, as the banking crisis demonstrated. Bank borrowing is in effect being underwritten by central banks thus the low interest rates. In effect bank risk has been nationalised. Their profits on the other hand…

I am not sure that I follow you Peter. I am very clearly saying that there is a risk to bank lending, and that there is a charge for this.

If you are saying that there is a risk to bank borrowing from the Bank of England then I would agree: but this is not regulated through the interest rate, it has to instead be regulated through capital requirements. In that case interest rates remain irrelevant.

Makes sense to me.

And one conclusion has to be that since the government can ‘borrow’ at zero interest it has to be the sensible way to finance the basic needs of society.

To borrow through the markets is to court penury to no advantage.

For decades the government has been able to raise finance more cheaply than through the private sector. This is not news. That it can have effective zero cost is something of a novelty.

The entire premise of ‘Privatisation’ was essentially a lie to cover a lack of political will for elite financial gain. And my word! hasn’t it been a good ploy ? Four decades post Thatcher and Reagan the public still hasn’t spotted the deception and still keeps ‘cheerfully’ paying the bill.

I would have thought that a bank’s overheads, (it’s branches – if it has any – employees, overpaid CEO, computer systems and so on) would imply that creating loans has a cost.

To manage default risk: yes. I agree.

G Hewitt says:

“I would have thought that a bank’s overheads,…. would imply that creating loans has a cost.”

Clearly there are costs associated with providing a banking service, but I think you’ll find that the majority of businesses are still paying transaction charges. What we call ‘free banking’ for individual personal accounts is largely a fiction and government insistence on all its payments being to bank accounts (for benefits, pensions etc) is underwritten directly or indirectly by government. Add to this the inevitable ‘set-up charge’ for loans, mortgages credit card transfers etc. and much of this administration cost is pay as you go. Not forgetting of course humungous sums of money rattling around the system between ‘payday’ and the money being spent, in accounts yielding derisory interest.

Interest on capital is probably virtually unencumbered by admin overheads. And free to generate in effect by the grace of HMG/BofE.

Imagine the profit returns to the building industry if all materials and land for new-build housing estates were provided at government expense. I think that a fair analogy.

“You are not sure I am right” .. there is no opinion being offered. The link shoes charts with 3month T Bills and 2 year Treasury Bonds trending higher.

So there is can be no wrong as it is actual data.. no differentials, no anything else!!

Of course you are not right: not in a trend over hundreds of years

A bump here or there does not change that

Sorry, but let’s get real, shall we?

How about a bit of analysis on quality of data? I’m not a gambling man, but I’d wager the quality of data from 1323 can’t be relied on too much…

Actually, I suspect it’s pretty good

All inflation measures work on indices

The price of basic commodities is pretty well recorded over time

Tim says:

“How about a bit of analysis on quality of data? I’m not a gambling man, but I’d wager the quality of data from 1323 can’t be relied on too much…”

And I’d wager it’s more reliable than current government unemployment figures which are deliberately misleading (relative to recent historical figures). As indeed I suspect are a lot of other published figures.

In control engineering there is something called the Nyquist stability criteria which describes how stable a given system is – is it optimally damped

– the chart showing change in prices seems to suggest that over the period 1800 to the present – in effect three distinct periods – there has been increasingl;y better “damping” in the economy over each successive period so that if there is an upset (external shock) – price stability seems to recover more quickly.

An excellent description

Mike Parr says:

“….. there has been increasingl;y better “damping” in the economy over each successive period so that if there is an upset (external shock) — price stability seems to recover more quickly.”

So following the next financial calamity (which is widely anticipated to be going to be a lulu) it would be reasonable to expect the downward trend of interest rates to continue (?)

And from where rates are currently there is not very far to fall. Which of course would explain the orthodox urge to see rates ‘normalised’ so we won’t have to address the systemic flaws in the entire system, but can get away with another temporary sticking plaster.

On what has been a very long road to a wider acceptance of MMT, it seems to me (not an economist) that the points Richard has raised here might be very helpful if you can get them across to a bigger audience.

Fiscal policy, aka adjustment of government spend and taxation, is a political choice – not a choice for the BoE Governor to make!

Discuss …

Agreed