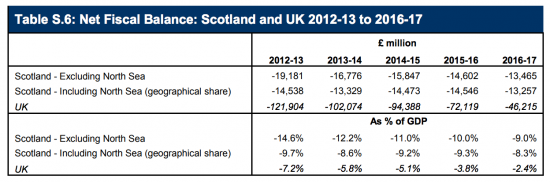

I have been continually bemused by the fact that GERS - Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland - and its equivalent data for Wales and Northern Ireland - says that Scotland runs a deficit so much larger in proportionate terms than that for the UK as a whole. The current GERS data is as follows:

Proportionately the Scottish deficit is suggested to be, after North Sea revenue is taken into account, 3.45 times that of the UK as a whole. The trend is meant to be growing, but that's broadly speaking the impact of oil revenue decline. The figure is, however, picked on by some commentators to show that Scotland is unable to meet its own costs and is subsidised by the rest of the UK.

I have been ruminating on this. What follows is speculation at present: think of it as an idea put out for peer review right now and not a final argument.

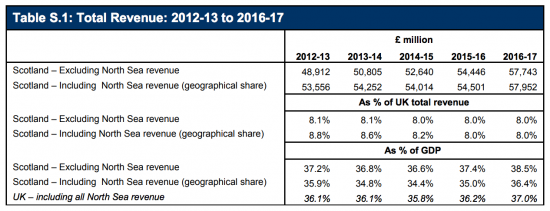

First, a few more facts. Start with revenues:

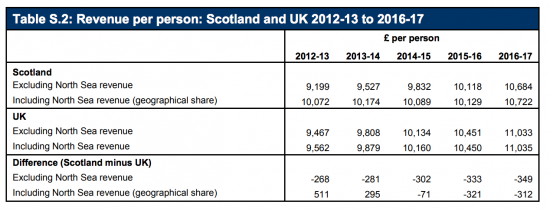

It will be noted how insignificant oil revenues now are. It will also be noted that it's suggested that Scotland collects about the same share as the UK as a whole, give or take North Sea oil and GDP. Per head though the figure is slightly different:

Until 2013 Scotland collected more per head than the rest of the UK, Now it collects less: this is an obvious reason why the scale of its deficit appears to be growing.

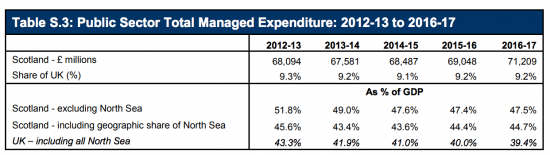

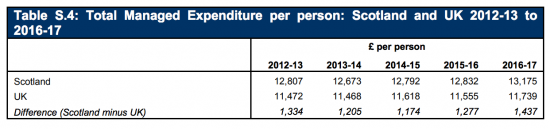

It is however said that the real problem is in spending. These are the totals:

And this is spending per head:

Revenues per head may look slightly adrift, but here things look really awry: it's always said Scotland outspends the rest of the UK as a result of what's called the Barnett Formula. Shoulders are shrugged as a consequence and the apparent deficit in Scotland is accepted as a fact. But I want to speculate for a moment on whether this is entirely appropriate.

Much, but not all of my criticism of GERS has focussed on the fact that almost all the significant revenue figures are estimates based on either data extrapolation of the whole of the UK or on relatively small samples for Scotland meaning that I think that there is doubt about whether all the major tax revenues are fairly stated. I have also on occasion questioned why it is appropriate to apportion some costs to Scotland. But when I was reading GERS this year another thought occurred to me on the expenditure side of the equation. This is the note in GERS that got me thinking:

Public sector expenditure is estimated on the basis of spending incurred for the benefit of residents of Scotland. That is, a particular public sector expenditure is apportioned to a region if the benefit of the expenditure is thought to accrue to residents of that region.

This is a different measure from total public expenditure in Scotland. For most expenditure, spending for or in Scotland will be similar. For example, the vast majority of health expenditure by NHS Scotland occurs in Scotland and is for patients resident in Scotland. Therefore, the in and for approaches should yield virtually identical assessments of expenditure. However, for expenditure where the final impact is more widespread, such as defence, an assessment of ‘who benefits' depends upon the nature of the benefit being assessed. Where there are differences between the for and in approaches, GERS estimates Scottish expenditure using a set of apportionment methodologies, refined over a number of years following consultation with and feedback from users.

The for approach considers the location of the recipients of services or transfers that government expenditure finances, irrespective of where the expenditure takes place. For example, with respect to defence expenditure, as the service provided is a national ‘public good', the for methodology operates on the premise that the entire UK population benefits from the provision of a national defence service. Accordingly, under the for methodology, national defence expenditure is apportioned across the UK on a population basis.

The methodology note on the GERS website provides a detailed discussion of the methodologies and datasets used to undertake this task.

The emphasis on for and in by use of italics is in the original.

Might I say now that I have read the GERS methodology notes with care? Might I add that I know they are accounting adjustments to both income and expenditure (many of which are the equal and opposite of each other)? Might I also add that right now I cannot see that they explain in any way the matter I refer to below? Nor, as far as I can see, does anything in the detailed methodology notes on expenditure and income. And then can I note the following statement in the GERS income methodology note:

These data are presented on an accruals basis ... The international standards for National Accounts and Government Finance Statistics use the accruals basis rather than a cash approach. This is because accruals accounting reflects a more accurate picture of when revenue is due and spending occurs than the more volatile alternative of cash, which, for example, records when bills are settled rather than when the expenditure occurs.

An accruals basis, according to the main GERS statement, means:

Accruals: the accounting convention whereby an expenditure or revenue is recorded at the time when it has been incurred or earned rather than when the money is paid or received.

Now I hate to be an accounting pedant here, but I am not sure I agree. Let me offer a third party view, found using Google on a web site called Accounting Coach. It says:

Under the accrual basis of accounting, expenses are matched with the related revenues and/or are reported when the expense occurs, not when the cash is paid. The result of accrual accounting is an income statement that better measures the profitability of a company during a specific time period.

As an accountant I will say straight away that this second version is what accruals really is, and not what GERS says it is. And this matters, and could explain why GERS appears to sell Scotland so short. That is because the GERS version of accruals accounting treats income and expenditure as independent variables even though it then goes on to compare them when computing a deficit. So in GERS income is treated on an accruals basis and so is spending in the strict sense that it is not cash flow that is declared in GERS but sums receivable and payable. So far, so good: in accounting terms this makes sense.

But accruals also requires that the expenses be those recorded to incur the income. Or, perhaps more accurately in government accounting terms, the income shoukd be that received as a result of the spend since, as a matter of fact, national income accounting shows that government spending is a part of GDP and is then a driver of tax revenue, and not the other way round.

This is where my new problem arises with GERS. I agree that a significant part of the spending in GERS - at least sixty per cent of it - is devolved spending managed by the Scottish government and unsurprisingly as a result almost entirely spent in Scotland.

And of course I agree that some of the spending by the UK government for the supposed benefit of Scotland is also spent in Scotland. There are defence establishments, for example, in the country.

But the point that some spending for the benefit of Scotland is not spent in Scotland would not need to be made if it was not true. I have perused the GERS data and the GERS data set and admit I cannot be sure I can determine the sum in question with complete accuracy at present: I stressed at the outset that this is not a finished piece of work. The best estimate appears to be that the sum in question is unlikely to exceed £10 billion, but I stress, this will need refining.

The point then is this: a significant sum is spent for but not in Scotland. The cost is recorded as Scottish. But because the version of accruals accounting in GERS is a distortion of what that accounting concept actually requires, which is that costs and revenues be matched, the tax paid as a result of that spend does not appear to be credited to the Scottish tax account. Instead it is credited where the activity takes place.

Take an example of spending on the civil service in London charged to Scotland in GERS. The cost is in GERS. But where is the revenue? That's in south east England.

If that is the case, and I think it is, then I would suggest that the accounting base used for GERS is misleading, and the distorted view of accruals accounting as defined for GERS might suggest that this is by design.

If GERS was to present a true picture of the Scottish income and spending arising as a result of activity for the government then not only can costs from the rest of the U.K. be attributed to Scotland but so too should the tax resulting from them be attributed as well.

Actually, it's rather more than a basic basis of attribution that is required. What we know, after all, is that government spending has what is called a multiplier effect. In other words the impact of the spend ripples out into the economy because, of course, the income recipient of that spending does in turn spend what they earn. And the recipient of that spend then spends, and so on. And if a lot of government spending for Scotland is actually spent outisde the country - and it may well be - the revenue side of GERS may be seriously deflated and have no real connection with spending side of GERS at all under the accounting convention adopted because not only is the first and direct stage of tax collected not attributed to Scotland but nor either is its multiplier imoact, which may be much larger.

I stress, I can't be sure as yet that this explains why the Scottish deficit (and come to that the Welsh deficit ) is so disproportionately stated. But I can say three things.

First, it needs to be confirmed whether the tax paid on spending for Scotland is credited to GERS. Incidentally, the adjustment the other way would be tiny.

Second, the sum in question needs to be calculated accurately, as does its multiplier effect.

Third, if the revenue in question is not credited then it is entirely reasonable to say that the accounting basis for GERS is flawed and that it is very likely to seriously overstate the Scottish deficit as a result. That would be because the reason why Scotland is so consistently reported to be dependent on the rest of the U.K. is at least in part because the rest of the U.K. takes tax revenue that should be credited to Scotland and would be if Scotland was really in charge of its own affairs.

I look forward to informed comment, please.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

As for welfare, it’s overwhelmingly pensions, isn’t it? And the UK state pension system is famously unfunded – the pension payments coming in aren’t ring-fenced and invested for pension use only, they’re treated as general government funds, right?

Scots do well, but more often than not by moving down south. With the differing levels of salaries between Scotland & England (and the different cost of living), I suspect the outgoing pension payments will be skewed far from per-capita parity, before even considering life expectancy.

Are you comparing one kilometre of the M1 to the single track road near my house?

I think that is exactly what is being done

Unionists have some pretty strange ideas

I am not sure they leave the well beaten track that often

Richard,

Thanks for this. Just so’s I understand this properly, or could gain further clarity.

If we take something like the Trident replacement, which is arguably a ‘benefit’ to the whole of the UK, we can assume that several Admirals and associated staff will be based in London? If that is right, then their personal multiplier effect will largely be contained in the SE of England. Because other organisations they would have to consult with, UK contractors US advisors, etc, would all find it ‘handy’ to have offices near them then that too is a multiplier effect. Hence the SE immunity to, well, anything at all really.

One could almost assume that the UK, absent the SE, is being unfairly treated in overall economic terms?

Yes to the last

Which is why all the region has mysteriously lose out

I really despair when some Scots & others exult over this “proof” that Scotland is a basket case. As many of us have pointed out, if that is so, then it doesn’t say much about 300 years of rule from Westminster.

But, it raises another point that those in other “regions” of the UK should be demanding answers to. How are “we” in the north (of England), or in Liverpool, or Cornwall or Wales or NI (thanks, Mrs M, for the recent bribe) doing? Where are our GERS? And what kind of government is it that has allowed the UK economy to become so unbalanced such that London & parts of the SE have become disproportionately wealthy while the rest have stagnated?

I have never understood why there has not been a revolution in Britain. (Well, I do actually, it’s because the aristocracy and then the oligarchy have conceded just enough to keep the peasants in check, backed up by force when required, while all the time retaining all the real levers of power)

If your assumption that the money spent FOR Scotland is allocated on a Gross basis ie including inome tax. 100 gross tax 30 net 70. Then you are absolutely correct. There needs to be a adjustment for the tax as follows. Credit scottish income 30 debit rUK 30 to take the revenue side of GERS up to the correct figure.

However and this is where it gets really messy and interesting. If say part of the Gross charge is for services that are purchased from a supplier, eg bombs to drop on some innocent party. So too does the tax on salaries of those workers in the bomb factory need to be creditied to Scotland. As you would be aware there is very little non wage component in a full supply chain so for all practical purposes close to the entire Gross expenditure allocation needs to be mirrored with a credit to revenue. Lets say 95% for arguments sake. That blows a very large hole in GERS and even this excludes the “multiplier effect” from the calculation.

This is why I argued that the multiplier had to be taken into account

I was looking at one dimension of GDP and you another

Remember there are three methods of estimation

You might consider looking at the balance of payments too.

These are published on a regional basis by HM Customs and Revenue on a quarterly basis for Scotland England Wales and NI https://www.uktradeinfo.com/Statistics/RTS/Pages/default.aspx

Scotland going back as far as records exist has a significant surplus and England has a deficit running to 100’s of billions annually. NI and Wales bump along undramatically.

HOWEVER

1. Oil appears to be credited to either England or to ‘unknown’ region for 4 or five technical reasons (and Scotland is shown as a net importer of petrochemicals from England with 23% of Scottish imports counted this way)

2. Whiskey exports are credited to London and the South East of England on the basis of VAT registration of companies like Diageo

3. Exports of Scottish gas or electricity are counted as exports from the English regions as that is where they leave the U.K., and supply of gas and electricity to the rest of the UK from Scotland is not recognised

Clearly the Scottish trade surplus is hugely understated, and the English deficit is actually more serious than it already looks.

These regional trade balances do not fairly represent exports to the world of an Independent Scotland, and its ability to support the economy

I have commented on this recently

And oil has been subject to a recent adjustment

Add to that all the Company Tax paid by companies that trade in Scotland.

For all the profits made by Tesco, Sainsbury’s, John Lewis, Dixons, Apple etc etc … in Scotland the tax paid is credited to London or South East of England because that’s where their office is registered.

Those taxes swell the income figures for that region but diminish the revenue for Scotland despite the tax being ‘earnt’ in Scotland.

An attempt at approprtionmnent is made

But let’s be clear, GERS has no confidence interval on it so it’s very rough and ready

So in summary, as I see it, the Scottish account is debited with a per capita share of the cost of running UK government departments such as the Foreign Office, DWP etc. However, as most of the activities for running these departments takes place outside Scotland, e.g. Whitehall, the economic benefits and the workforce taxes are not accredited to the Scotland account.

That’s not the entirety. It’s not just the cost of running these departments but what they spend and where as well.

Well done.

I love this bit: “Take an example of spending on the civil service in London charged to Scotland in GERS. The cost is in GERS. But where is the revenue? That’s in south east England.”

Most British people don’t know this but the “net contributor” / “net beneficiary” nonsense is a uniquely British phenomenon the origin of which can probably be attributed to the IFS. The rest of the world is aware that Fiscal figures alone are meaningless out-of-context.

Your contribution here has shown us that the fiscal figures used in such estimates are seriously dodgy as well.

I hope that’s the outcome

[…] For those who want more information, look at Richard Murphy’s blog, which, apart from a much more detailed explanation, also has a number of very interesting comments. http://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2017/08/25/gers-is-this-why-it-always-says-the-scottish-deficit-i… […]