There’s been a lot of discussion about the need for public sector cuts. Give or take the public sector employs about 5 million people. If, as is demanded, there should be public sector cuts of 10% then maybe 500,000 people will lose their jobs.

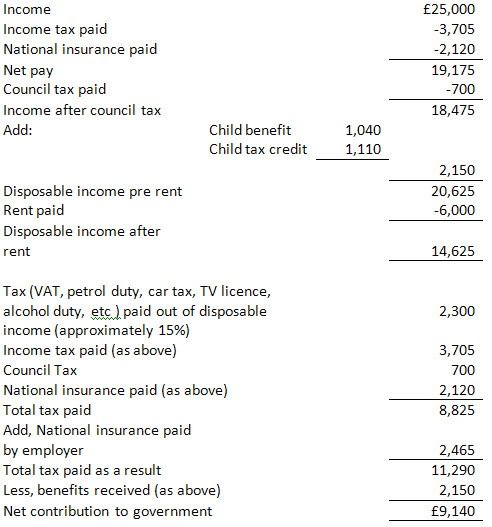

I have considered the consequence of this by doing a simple exercise. I have done a case study on the cost of a person earning £25,000 per annum who is a single parent with a child of school age, paying £500 a month in rent and £700 a year in council tax losing their job. The assumptions are slightly simplifying: benefits are harder to calculate in more complicated households. The rate of pay is slightly above mean and significantly above median UK pay. But £25,000 is a good, round number.

The total tax paid and benefits received by this person look like this:

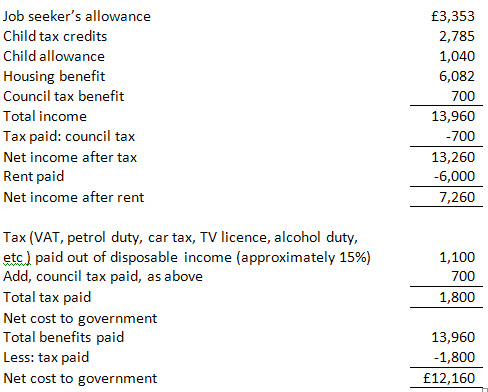

Now assume the same person was unemployed. They would get the following benefits:

Now assume the same person was unemployed. They would get the following benefits:

The total lost to the government if this person loses their job in the private sector is the addition of the total contribution lost plus the total cost paid. That is £21,300.

It could be argued that the cost is less in the public sector because tax deducted goes straight back to pay the employment cost. It so happens the net effect is the same. In that case the comparison with the private sector is maintained here.

The actual cost is higher though. The person in work has disposable income of about £14,625; the same person unemployed spends £7,260. That is a difference of £7,365. In other words they are twice as well off in work as out of work. But, most importantly, of that difference at least 65% (http://www.statistics.gov.uk/pdfdir/qna0609.pdf table D using 2008 figures) will support other people’s wages plus the taxes they spend on goods and services. Assuming these other people pay taxes at about the same overall rate as the person in the above exercise (and this is likely) that means about 36% of that difference will indirectly go in tax as well. That’s about £1,700. So now the benefit of keeping the person in work is £23,000 and they are only paid £25,000. Put it another way: 92% of the cost of cutting a £25,000 a year job when we have less than full employment is paid by the state.

In that case it is abundantly clear that paying to keep people in work pays — especially and even particularly if what they do has long term benefit that saves cost into the future. That cost saving — for instance from green efficiencies - has only to be £2,000 for it to be entirely worthwhile creating a job out of government spending to keep this person in work.

And that is before any account is taken of the social costs of being in employment, which are substantial in terms of reduced crime, improved educational outcome, better health, and more besides.

Now let’s reflect on the fact that in reality the average direct cost of employing an average public sector employee is less than this. Let’s make it around £21,000 — more like median pay — and then note that 500,000 at this pay rate will supposedly save £10.5 billion in the wage cost of the government. Putting these half a million people out of work will save us about £0.8 billion. That’s misery for 500,000 people and their dependents to save just £1,600 per job lost.

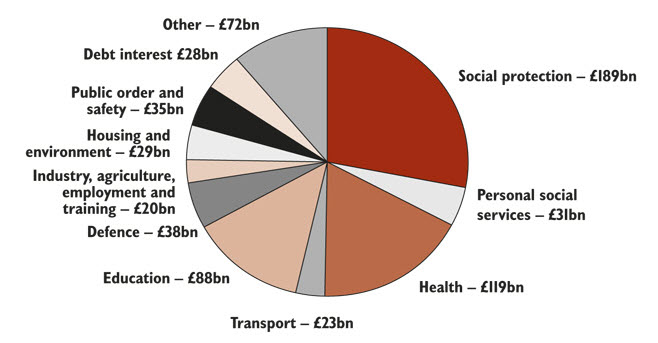

That though is not the end of it. Total government spending is £671 billion, split down like this:

So to cut spending by 10% £57 billion of extra cuts are required on top of sacking 500,000 people. These savings would need to be made up of:

So to cut spending by 10% £57 billion of extra cuts are required on top of sacking 500,000 people. These savings would need to be made up of:

1. Reduced benefits, which will result in reduced consumer spending, or

2. Reduced payments to private sector contractors to provide work to the government.

Either way there is reduced demand. £57 billion of reduced demand. Of which 65% approximately will go to labour. That’s £37 billion of labour cuts then. At £25,000 or so a head (approximately) that’s over 1.5 million more unemployed.

That, with the losses from the public sector adds more than 2 million to unemployment — making well over 4 million in all. Some consider this likely, I know.

But what is the effect on public spending? Maybe 92% of the cost of this cost in lost wages will fall on government either by benefits paid or lost revenue. That’s £34 billion. And that’s before we deal with the massive social and crime related costs of that level of unemployment and the collapse in our long term prospects.

So, to achieve total savings of maybe a net £4 billion in borrowing (£3 billion net from private sector cuts and about £1 billion net from public sector employee cuts) this policy would put 2 million people out of work.

Now I know all the problems of extrapolation in here, and I know that not everyone will get benefits in the way I have outlined above (but those that don’t will suffer even more extreme losses in income — compounding losses elsewhere) but frankly all analysis in this area is moving into the unknown, economically and statistically speaking. And losses to government may also be bigger than I suggest — after all out of the £57 billion of non-labour cost cuts required £20 billion will be lost profits and rents — and they could result in £6 billion of additional government tax losses, tipping the equation in the direction of any cuts in government spending creating actual cost for the government.

Which makes clear that the logic of cutting government spending now when we have no jobs for those we make unemployed makes no sense at all. It’s profoundly annoying to have to reinvent the whole Keynesian argument in this way — because that is exactly what I am doing — but needs must precisely because so many do not seem to understand this obvious fact.

Of course this situation will eventually change: private sector demand will pick up and employment with it. But right now there is no sign of that and to cut now would, I can confidently predict, produce something like the outcome I predict here. Put simply: cut spending and we’ll increase government debt. Perverse you might think — but true, and exactly what Keynes predicted.

What is more, the reverse is true. Increase spending now and the multiplier effect which compounds the impact of cuts in the above analysis goes into reverse: more jobs are created, revenue flows to government, benefit spending falls and government debt goes down with it.

The answer is simple: if we want to get out of the mess we’re in we spend. It’s the only way to reduce government debt at this stage in the economic cycle. It worked in the 30s. It will work now. Let’s do it.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Well done, Richard — this should go straight to The Guardian!

Brilliant Richard! in the process you singlehandedly contributed millions to the economy….think of all those cups of coffee at 80p/cup that the economists in Whitehall consumed whilst you did their job for them! It kept lots of people at work — coffee importers & instant coffee makers, lots of coffee distributors, van drivers petrol station people, highway patrol men busy, as well as glass jar manufacturers. Then there were the farmers that milked the cows & the sugar importers/manufacturers/distributers…and the folk in the water treatment plant, & those in the power stations generating the electricity to boil the kettle….and the lady who washed up the cups at the end of the day… and… 😆 😆 Seriously, a nice application of Murphy-Kensyon economics. 😛

1. our unemployed friend is receiving a council tax credit as a nullification of the council tax. Subtract £700 from real income and real tax, as all it does is inflate the state ‘income’ (read: receipts)

2. So too with the National Tax paid by the Employer. The employer is adjusting income to pay it, thus a reasonable comparison can only be made of the employer’s cost of maintaining that job in existence: employed-dude’s income AND tax should be £2460 higher or otherwise correct for the £2460 which as something NOT stated as income IS states as tax. Either way, the difference would look goosed.

However there are many ways to look at the statement “The only way to cut government debt is to increase government spending” which might be true by some calculation, but the only way to really cut government debt would be to reduce spending or raise taxes, because a larger government budget does not NECESSARILY save more private sector jobs from which taxes are derived to fund the “rayonnement” of publicly funded compassion.

As for the telegraphing effects on the consumption driven parts of the economy, the degree to which a reduction in unemployment benefits would have on it is not 1-for-1, either because part of it will not go through the conventional economy but rather underground, or not get spent, or be structually less due to government’s cost of collecting it to begin with and the attendant ‘fell off the back of the lorry’ problem that comes with government collection of taxes.

I’m not hostile to your scholarship here, I just don’t think it won’t lose every last one of its’ advantages due to the externalities associated with the fact that a process like this can only work if it’s running like a Swiss watch and nothing ever does.

However, I do think I know what you’re trying to incrementally do from a higher altatude, and that’s to try and laugh off the Laffer Curve without engaging it directly.

The two above responses are indicative of today’s ignorance of macroeconomics (and the poverty of its teaching); Laffer has not been taken seriously for years, even by neo-liberals. As for ‘Murphy-Kensyon’ economics … a sad case I fear.

The govt. is already in debt up to (and over) the ears. It will have to borrow even more to enable it to spend. And, on what it borrows, it has to pay an extortionate rate of interest because they are seen as a bad bet.

And – in the end – whatever is borrowed has to be repaid.

As to any appreciation of Laffer – Brown and co. probably now consider it to be the jollity with which they will slither off into generous taxpayer-funded retirement.

Mike

Did you read anything I wrote before you commented?

Richard

@Richard Murphy

Okay, owing to the trend, and assuming that the benefits of taxation are true, the question is where to stop? Do you not believe that there is a point of diminishing returns on the rate of taxation at all? While some perceive western European rates to be high for them, what would be too high for a western European?

Let’s say that rising taxes and enlarged central government budgets ALWAYS reduces unemployment – let’s just make that assumption for a second. You reach full effective employment through higher taxes, more people are paying more taxes, wages rise due to a shortage of workers until their product is uneconomic and Mr. Private Sector Producer locates equilibirium in that environment…. but when does taxation?

At what rate do you think you reach the point of diminishing returns? 75%? 80%? Coupled with the inflation created by high wages and curtailed at the same time by erasing that disposible income?

It’s a bubble waiting to happen, only much worse in that migher taxation is coupled with either cost or social programes that dissuade individuals from saving or investing.

Seriously – why will no advocate of statism say what rate of tax is structurally appropriate or too much? Have you ever notices that no-one brave enough to say that it must be higher can’t imagi9ne it being TOO high, or saying what it SHOULD be?

Nice illustration. However if we actually maximised long term value created out of government borrowings I would be a happy chap.

Where’s our Hoover Dam?

The tube needs finishing and some wind farms and replacement of our aged nuclear power stations wouldn’t go amiss. I would also like some new hospitals on our balance sheet; not rented on a bizarre PFI deal aka. lets pay a fortune in interest so we can account for it as an operating lease.

Its such a shame so much money was spent on systemically important banks! Well at least the big four should get some restructuring fees out of it. Perhaps the partners’ cleaners and nannies will benefit. Trickle-down myth anyone?

Joe

You really do miss the point

I’m not a statist

I am a democrat

It’s a remarkable system you really should explore some time that provides the checks and balances I think you are looking for

Richard

The example only looks at one side of the equation.

For every pound spent keeping somebody in a job, a pound will have to be taken from somebody else working in a different job. Because of those jobs being taxed more heavily, many of them well cease to be viable, meaning those too will need to be propped up to, further increasing the burden on others and so on ad nauseum.

All that approach does is harm productive businesses in order to prop up unproductive businesses, which in the long run can only result in higher unemployment.

Richard,

But on the subject of checks and balances, surely one thing that will stop the private sector from “bouncing back” is if people feel more secure and better paid (particularly when pension schemes are taken into account) in their jobs in the public sector. After all, would many public sector employees leave their job to join a new, start-up business.

So while I think it is right that, for example, unemployed builders should be paid by the State to insulate houses, and while it is also generally right that it is better for someone to be employed by the State than it is for them to be unemployed, there needs to be some balance so that State employment as a “safety net” does not actually become a glass ceiling that prevents people joining the private sector and thus effectively deepens the recession.

But I think where you lose credibility is in the view that you seem to have that a bigger public sector is always better. Because if it is a matter of checks and balances, if increased public spending deals with a downturn, surely in boomtime spending should be dropping? But you never seem to answer the question of when it is appropriate to lower public spending.

It’s so frustrating that, when you’ve taken the initiative by setting out what you believe – and clearly acknowledged your assumptions and the broad brush approach you’ve taken, none of the Laffer apologists – would they tell us if they’re in any immediate personal danger of losing their jobs or suffering financially? – can respond with more than a jibe that you haven’t seriously engaged with Laffer.

Quite apart from who’s position might be correct – and I’ve seen no more convincing argument than the one you’ve given us – the Laffer supporters really have to do more than regurgitate simplistic and unsupported assumptions if they want to win their, probably unwinnable, argument.

At the very least, you’ve made a case that demands an answer….and abuse isn’t that answer. But please don’t delete the abuse – the abusers are illustrating so clearly the poverty of their argument.

To Paul above:

I don’t doubt the good intentions of your comment, but you betray a profound ignorance of basic economics—or else a stubborn adherance to the principles of Thatcherite ‘handbag economics’. Under current conditions of potential deflation, goverment could print money to create extra jobs. And even if it borrows the money to create jobs—that money can be repaid later out of the extra growth.

George,

I’m not an economist but then, economics, like nutrition, isn’t a science. After all, to read this blog you’d think all we had to do to be increasingly wealthy is shut down the private sector, give everyone jobs in the public sector and print money so they all get paid loads. Somehow, my innate scepticism thinks that cannot be right but as you are understand economics I bow to your superior intellect.

I don’t think its unreasonable to ask whether, at some point, the public sector needs to shrink. I accept now is probably not the time. But the time never seems to be right to those who believe that most of the economy should be brought under state control – ah, I’ve answered my own question!

George,

The government could certainly create more jobs in the short term by borrowing money, but that will not create extra growth beyond the natural level once the corporate welfare has been withdrawn. At best, the government will have second guessed where the demand will be and the subsidised jobs will be able to continue unsupported. At worst, there will be no demand for the subsidised jobs, which will cause stagnation as redundancy steadily removes them while other jobs struggle to fight their way through. In either case, the extra tax to repay the debt will suppress activity.

If a government is insistent on trying to borrowing or inflate its way out of recession, it would make more sense to give the money to the public as a per capita dividend, so that whatever jobs are retained reflect genuine public demand and are therefore more likely to be viable after the recession.

Paul:

‘Somehow, my innate scepticism thinks that cannot be right but as you are understand economics I bow to your superior intellect.’ Come now Paul, that’s a very traditional put-down (are there two Pauls or only one?).

‘that will not create extra growth beyond the natural level’ … sounds like you believe there is something called the ‘natural rate of unemployment’… ‘the extra tax to repay the debt will suppress activity’ and do I hear echoes of the Barro-Ricardo hypothesis.

It all suggests you are simply spouting the sort of thing Patrick Minford at Liverpool would have taught in the 1980s and 90s. Yes, economics is ideological—problem is that we seem to be on opposite sides of the ideological divide! And of course, you’re quite entitled to your opinion; I have no problem with that as long as it’s backed by factual evidence. But these days, the neo-liberal case is looking rather weak.

George

Richard there are the wrong sums!

In a marginal blinkered sense perhaps the logic is appealing, but the flawed assumption is that the marginal case works at all scales. Clearly it doesn’t. After all, if no one actually worked in the UK (or if everyone worked in the public sector) there would be no taxes and no welfare benefits.

The more significant flaw is to assume labour is infinte when in fact it is a scarce resource. When the government employ labour they are denying that resource to other activity. In the market place the price mechanism will work to solve that problem, but the price mechanism does not apply to government spending. The marginal cost to government of the extra state employee is the tax foregone on that person working in the private sector, and the tax forgone for the lost productivity. So reduce the size of the state payroll and increase the tax take.

Most people would accept there is a balance, but it has tilted too far, and is exacerbated by the size of government borrowing.

George: “‘that will not create extra growth beyond the natural level’ … sounds like you believe there is something called the ‘natural rate of unemployment’”

Please. That’s a very sloppy attempt to link two separate concepts.

“‘the extra tax to repay the debt will suppress activity’ and do I hear echoes of the Barro-Ricardo hypothesis.”

I’m astonished that anyone would even try to disagree with the idea that taxing activity suppresses it. Alcohol, tobacco, fuel, etc. are all taxed heavily on the basis of the universally acknowledged principle that when you tax something, you discourage it. Are you really try to say that is false?

Why are they the wrong sums?

Labour is an infinite resource when there is unemployment. Don’t you get that?

I am staggered that anyone can be quite so blind as to not notice there is rising unemployment and can write the above.

Yet again – please leave the dogma behind – and open your eyes.

Do you necessarily suppress demand when you tax a good. Not necessarily. Taxing booze in the UK doesn’t seem to suppress demand much on a Saturday night in the Bigg Market (that’s in Newcastle, by the way!) More seriously, the demand for petrol seems not to be much restrained by the high level of tax thereon, much as many people might like to see petrol use suppressed a bit.

Paul

You would clearly like it to be thought that you’re an economist – but James has rumbled you

You assume that the demand curve has a consistent downward slope i.e. as price rises demand falls – hence the characteristic you describe

The reality is that this is just no true – upward sloping demand curves are entirely plausible – and exist

It is quite possible for demand to rise as price rises

And for there to be very limited, no or even negative price elasticities of demand

For more read http://www.debunking-economics.com/

But you’re wrong, as usual: of course there is a strong reason fro thinking taxing something need not necessarily suppress it, even if it often does

Richard

Richard, the only long term systemic unemployment we have is the underclass paid by this government not to work. But even with long term systemic unemployment labour is still finite

Alastair

You do believe in a perfect world where unemployment = zero always. Amazing!!!!

Tell that to 2.2 million unemployed and rising

Your stupidity (word wisely used) knows no bounds – or so it would seem

Would you mind noticing we do not have full employment right now and comment on the world as it is – not the world as you would lkike it to be

Then I’ll take you seriously

Richard

PS have tyou gone round telling people – probably some members of your family – they’re members of the underclass? How long was it before someone hit you? Did you wonder why?

Richard, I live in a very real world – would be happy to welcome you to it 🙄

My suspicion is that unemployment figures are actually suppressed, by the large numbers of exclusions. Also do we beleive that increasing student numbers are a symptom of

a) Any increasingly intelligent pool of young people (more than ever before) wanting to study.

or b) An increasing number of young people who can’t find work but whom the government does not want to categorise as unemployed.

I feel bad about querying the value of education in this way, and I know many will say that I am belittling young people’s acheivements. However I can’t pretend not to be sceptical. I note that apparently all this education is only paid for through high levels of debt imposed on the students.

Bluntly, I think we have a very high level of unemployment and it’s all worse than we think.

There is a mistake in the sums or at least a wrong assumption, Tax on unavoidable expenditure in case two would not stay at 15% it would jump to at least 25% of disposable income.

Tim

“Paul

You would clearly like it to be thought that you’re an economist”

No, I’m not an economist, just a person who happens to live in an offshore jurisdiction, wants a sustainable future and is genuinely interested in how we achieve that. If I ever gave the impression that I wanted to be though of as an economist I apologise.

I am not a libertarian, or an apologist for anything, just someone that wants to bequeath a better future to my kids – as I am sure you want to as well. It’s just question of how we do that – my kids are young (like yours) and I don’t want them to live in a world as materialistic as the current one. But I don’t want them to live in poverty either and I feel your views led that way, because I suspect, as a non-economist, that the private sector drives the economy. That’s all.

Paul

There are several Pauls here – 3 at least

You assumjed I was addressing you

I was not

If you used full names it would help

What is wrong with a little transparency?

Richard

James from Durham: “More seriously, the demand for petrol seems not to be much restrained by the high level of tax thereon, much as many people might like to see petrol use suppressed a bit.”

I think you’ll find it does James. When prices at the pump increase, demand falls. It might not be so dramatic that the roads become empty, but that doesn’t mean the effect isn’t there.

Also, try comparing the average price at the pump in the US with the price at the pump in the UK, then compare the average engine size and mpg of cars in those countries. Do you seriously want to claim that the price of fuel has no impact on the choice of car?

If, against the evidence, you’re going to insist that the law of supply and demand no longer applies, it’s going to take more than bare assertion to convince me.

Paul

I have referred you to evidence on this issue

Please refer to it – and stop berating other commentators when your own undertsanding is demonstrably wrong

The laws of supply and demand are not immutable – so your case is without foundation

Richard

Sorry Richard.

What is wrong with a little transparency? Well, in this case, I would lose my job if my full name was posted. Or else be asked to stop posting. So the current arrangement suits, with all its faults.

It is tricky to follow the conversation when so many participants are all called “Paul”. Paul Lockett of course is happy to give his full name and even a photo! I moved to a fuller title as soon as another James started commenting.

You appear to have demonstrated that welfare provisions are more generous than we can afford, and that the combination of tax and withdrawal of benefits creates a very high effective rate of tax on those just above the mean earnings level.

By your maths, someone with gross pay of £25,000 has a disposable income that is £7,365 higher than someone who is earning nothing. That is an effective tax-rate of over 70%. Not great reward for the effort involved. No wonder public-sector employees don’t cost us much more than the unemployed – but is that something to write home about? What you are saying is that we don’t reward people doing work much more highly than people doing nothing.

Your conclusions do not necessarily follow from this calculation. One might equally conclude that we need to rebalance our tax and welfare system so that effective and marginal rates of tax are lower and people are better rewarded for work.

[…] note my blog on the costs of cutting government spending has appeared on the Compass […]

[…] protected, consume healthcare and so on. All you do is cut one budget and add it to another. And, as I showed recently, that might give no real saving at all — indeed – it can add to government cost in many […]

Richard,

There appears to have been either a technical glitch or unintended offense given. I posted the following yesterday, and it showed at first as “awaiting moderation”, but now it has disappeared. If this was just a technical glitch, I take it you will have no objection to my reposting the comment. If it was a case of something within the comment being unfit to appear on your site, thus requiring the whole comment to be deleted, I would be grateful if you could let me know what it was, and what the moderation policy of your site is, in order that I can avoid this mistake again in the future. I am sure it would be a useful guide for others as well.

Original post:

You appear to have demonstrated that welfare provisions are more generous than we can afford, and that the combination of tax and withdrawal of benefits creates a very high effective rate of tax on those just above the mean earnings level.

By your maths, someone with gross pay of £25,000 has a disposable income that is £7,365 higher than someone who is earning nothing. That is an effective tax-rate of over 70%. Not great reward for the effort involved. No wonder public-sector employees don’t cost us much more than the unemployed – but is that something to write home about? What you are saying is that we don’t reward people doing work much more highly than people doing nothing.

Your conclusions do not necessarily follow from this calculation. One might equally conclude that we need to rebalance our tax and welfare system so that effective and marginal rates of tax are lower and people are better rewarded for work.

Richard

What you offered as evidence does not prove what you have claimed. I confined myself to responding to James as I found his tone to be far more civil, but as you have repeated your claim:

You said “You assume that the demand curve has a consistent downward slope i.e. as price rises demand falls – hence the characteristic you describe. The reality is that this is just no true – upward sloping demand curves are entirely plausible – and exist”

Yes, upward slopping demand curves are plausible, for luxury items or so called Giffen Goods, but they would have to be unusual exceptions to the general downwards slope of the demand curve. Just showing that they are plausibly isn’t enough to warrant an assertion that they exist in a given circumstance, such as:

“of course there is a strong reason fro thinking taxing something need not necessarily suppress it, even if it often does”

Not only has that strong reason not been given, but you’ve not specified which taxes you feel it applies to.

If you think that it applies to alcohol, tobacco or fuel, then you are arguing that the policy of discouraging the use of those goods by taxing them heavily is at best ineffective and at worst, it actually encourages their consumption. I don’t find that plausible.

If you think it applies to general business based taxes, you are contradicting many of your own claims about tax havens, because, if those taxes displayed an upward slopping demand curve, businesses would be deliberately moving to the jurisdictions with the highest tax rates.

If you’re still insistent that you can increase demand for a good by taxing it more heavily, I’d be intrigued to know which goods you think this applies to.

Paul

You clearly have not read Debunking Economics

The reality is that a demand curve can be both upward and downward sloping for one product, and can switch between the two

I agree, of course imposing a tax on a product usually reduces demand for it – but not always, and the exception is not always just for so called Giffen goods

My point was that you are relying on a model of economics that is just too simple to produce useful answers – largely because the assumptions on which it is built – such as rational behaviour by economic agents – are just not true

My point is that predicting response to tax is not as certain as you suggest – nothing more

Richard

I find the argument very unconvincing indeed. There seems to be a lack of clarity about costs versus transfers, economic costs versus accounting costs and similar. Much of the argument is predicated on the existence of a loony tax and welfare system.

If I understand it correctly, the argument says “The government pays £25,000/annum to keep the person in work and £23,000/annum to shed the worker. So the cost to the government of the job is just £2,000/annum. So if the public benefit is over £2000/annum, the public is getting a good deal!”

Firstly, what is the marginal economic cost of government funds? Some estimates put this as high as 200% of net revenue. Secondly, what is the private cost of employment to the worker? Thirdly what are the overheads of employment paid by the government? These factors substantially increase the overall cost of the worker. And what is the opportunity cost of keeping the worker in that job?

Much of the “cost” to government is self-inflicted through bizarre policy choices. The idea of paying people welfare in order not to work is pretty absurd, and at the heart of this problem. Accounting for not employing someone as a cost is really an artifact that disguises the economic reality.

The confusion over this example illustrates just how hard it is to disentangle financial and accounting mirage from economic reality. Having to add in the indirect taxation effects, costs of funds and Housing/Council Tax Benefits ensures that no satisfactory conclusion can be reached.

Is TRUK really saying that government decisions should be made on the basis of the financial analysis, rather than the economic reality? It seems so. But going down this route will accentuate the serious anomalies that have afflicted decision making for thirty years.

The best solution is to simplify the tax system by abolishing Income Tax, National Insurance, Jobseeker’s Allowance, Housing/Council Tax Benefit and VAT. Then you’d be able better to relate the pay to the financial (accounting) cost and the economic cost. Citizens’ Income and Land Value Tax would provide the tax base and welfare function regardless of employment levels. The mishmash of ad-hoc taxes and welfare payments wouldn’t obscure what should be a fairly simple analysis. And the “problem” of tax avoidance and evasion would largely evaporate.

Jobs seem to be treated in this article as an economic benefit, not a cost. All other things being equal (which they aren’t), shouldn’t we aspire to 0% employment? The vast majority of the population only go to work out of financial necessity. Working on the basis that 100% employment is a legitimate goal is perverse.

The problem of ballooning government debt should be solved by taxing unearned economic rents (especially LVT). Private and public spending on a baroque system of tax and welfare should be phased out ASAP, saving the labour of millions. The “problem” of aggregate demand shortfall should be solved through private spending of Citizens’ Income, not make-work paid for by production taxes. Is it that difficult to understand?

The main problem with your analysis is that you start from your answer and try to justify it. But your narrative is littered with flaws:

1. “It could be argued that the cost is less in the public sector because tax deducted goes straight back to pay the employment cost.”

Doh – the employment cost of a public sector worker comes out of government funds. The obvious saving to government funds is the net employment cost less the unemployment benefit. The lost indirect tax is harder to quantify as it depends on spending habits.

2. “In that case it is abundantly clear that paying to keep people in work pays — especially and even particularly if what they do has long term benefit that saves cost into the future. That cost saving — for instance from green efficiencies – has only to be £2,000 for it to be entirely worthwhile creating a job out of government spending to keep this person in work.”

Perhaps there is benefit in social cost terms, but “green efficiencies”? You are ignoring the funding cost of the increase in debt.

3. “And that is before any account is taken of the social costs of being in employment, which are substantial in terms of reduced crime, improved educational outcome, better health, and more besides.”

Social costs are difficult to quantify – but given that the “jobs for life culture” is no more, and labour is more mobile, there is a downward trend here. And don’t forget the social cost of long term welfare benefit dependency.

4. “Now let’s reflect on the fact that in reality the average direct cost of employing an average public sector employee is less than this.”

OR perhaps it is more – defined benefit pension schemes – the Health and Safety costs – longer holidays…

5. “Reduced benefits, which will result in reduced consumer spending”

Doh – this is about redistribution, but the spending will be the same

6. “Reduced payments to private sector contractors to provide work to the government”

And this sounds like an example of Brown double counting

7 “Either way there is reduced demand.”

As is this – its not reduced demand – its redistribution.

8. “Which makes clear that the logic of cutting government spending now when we have no jobs for those we make unemployed makes no sense at all. It’s profoundly annoying to have to reinvent the whole Keynesian argument in this way — because that is exactly what I am doing — but needs must precisely because so many do not seem to understand this obvious fact.”

Keynes had his time, and in his time the welfare state was emerging rather than endemic.

At the risk of being niaive, I have not heard anyone suggest that a major way of increasing the income to the government is the make more of an effort to actually collect the tax due to the – ie by clamping down on tax fraud.

Again, not my area of expertise but I remember once hearing that the government only actually collects around 60% of the tax due to them – in the mean time this investment in getting the additional tax in would likely create jobs in the HMRC (they could probably have their pick of a lot of very good but unemployed accountants and tax advisors at the moment)

I recognise that I may be way off mark here and overly simplistic – would anyone like to comment?

I do wonder if Alastair has ever read Keynes, or for that matter knows any economics. Pretty lightweight stuff I’m afraid—you’d ecertainly not get through my own course in macro 101!

Hi George

wouldn’t ever refer to Keynes as “pretty lightweight stuff”! can’t comment on your course – where do you teach it? Personally I found Adam Smith and David Ricardo more inspiring.

[…] already and in great depth. He’s a trained accountant, so you can read the well-explained maths here. But to simplify his thinking very quickly, consider it as […]

[…] I have shown it pays. […]

[…] does want to cut spending and throw us into deep recession and create at least 4 million unemployed as I have predicted — although that will not cut debt at all — as I have also […]

[…] Anything else will be an economic disaster. […]

[…] things follow from this observation. Firstly, spending pays for itself. As I have shown, this can almost be true in terms of taxation alone. But there is, of course, much more to it than […]

[…] out of work, that all these people will remain unemployed — at cost to the benefit system. And as I have shown here, Now let’s reflect on the fact that in reality the average direct cost of employing an average […]

[…] public sector workers redundant would, as I have previously suggested, put 1,500,000 private sector employees out of […]

[…] public sector workers redundant would, as I have previously suggested, put 1,500,000 private sector employees out of […]