The Labour government claims that it cannot afford to pay benefits for the elderly, children in poverty, and people with disabilities. That is nonsense. Simple economic analysis shows that these benefits pay for themselves.

This is the audio version:

This is the transcript:

Why is Rachel Reeves refusing to remove the two-child cap on benefit payments when, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility in the UK, doing so would actually significantly increase GDP on the basis of the spend that would be involved, and as a consequence, she would better meet her growth targets.

I ask the question because I genuinely do not understand what Rachel Reeves is doing when she is refusing to either restore the Winter Fuel Allowance for old age pensioners, or remove the two child benefit cap with regard to those who are now suffering it because they have three children or more, or generally unfreeze benefits, which is a policy that she's also pursuing.

The spend for achieving these goals would come to around £8 or £9 billion at the moment, although there is some debate as to the precise numbers involved, and I accept that the estimates will be a little inaccurate because they always are. But the point is, in total, this is less than 1% of government spending.

But more importantly than that, and more importantly from Rachel Reeve's perspective, because let's be honest, there is absolutely no evidence that Rachel Reeves thinks in the slightest bit about the hardship of pensioners who can't pay their fuel bills, or the hardship of children and their parents who can't afford to eat properly, or anybody else who might be on benefits come to that; if we just look at it from the economic perspective that apparently matters to her, then we are discussing fiscal multipliers and fiscal multipliers matter.

A multiplier effect records the amount by which the gross domestic product, the national income of a country, increases based upon an increase in government spending.

So, if you increase government spending by 1% and you increase gross domestic product by 1% as a result, you basically have a fiscal multiplier of one. 1% increase for 1% increase.

If you have a 1% increase in government spending, but you only get a 0.8% increase in GDP as a consequence, the fiscal multiplier is less than one. It's actually 0.8.

And if you spend 1% extra and you get a 2% increase in GDP, you've got a net positive effect of that spend and a multiplier of two.

Now, I won't go into the technicalities of multiplier effects more than that because it's going to be the subject of another video fairly soon in the future, but just understand that point at the moment.

The fact is that when the government spends money, it does not pour it into a black hole. Far from it. In fact. Somebody gets the money.

If you listen to many politicians, you wouldn't understand that. It is as if they do genuinely believe that every single pound of government spending is wasted with no further consequence for anyone whatsoever. But of course, that is simply untrue.

And the group in society who will spend every single penny that they receive from the government, and therefore inject it straight back into the economy, are those with the lowest levels of income. That obviously follows because we do know from government issued data that those with the lowest level of income have almost no savings at all, and therefore we can guarantee that if they get more income, they will spend it all because they need the things that they're going to buy and have suffered poverty because they have been denied them.

So, a pensioner who gets a £200 winter fuel allowance will spend it. They may not spend it all on winter fuel. They might spend it on buying Christmas presents for their grandchildren. It doesn't really matter.

Those who get an additional benefits payment because we remove the two-child cap may not spend it directly on the child. They might clear their rent arrears. They might spend it on having a warmer house, but they will indirectly improve the well-being of that child, and that does matter.

The point is, whatever we do in this category of spending, whatever is spent by the government goes via the recipient, the pensioner, the person on benefits, straight into the rest of the economy, because these people have what is called a very high marginal propensity to consume.

Basically, everything they get, they spend.

Now that matters because the higher, the marginal propensity to consume that somebody has, the bigger the multiplier effect is of giving them money to spend because the moment somebody starts saving out of the money they receive, you reduce the multiplier effect because the money is set aside and no longer fuels increased activity in the economy. Saving is dead money. So, as a consequence, for the government to spend money with the people who are going to spend it makes absolute economic sense.

Now, we do not know precisely what the multiplier effect in question is because the government don't tell us what assumptions they make about this multiplier effect.

But think about it. First of all, all that money that the recipients of these benefits get goes straight back into the economy, and as many of these benefits will not be subject to tax, it is 100% per cent of the money will go into the rest of the economy.

But the moment that somebody else receives it, first of all, they will pay over VAT, because much of this will go on consumption expenditure. And then they will receive the money into their business. And in that business, they will pay staff who will pay tax, and the business itself will pay other taxes, for example, corporation tax on the profit that it makes, and on, and on. Because once the business has paid money to its employees, they will then spend out of their net earnings, and the vast majority of people in the UK, at least 50%, have very few savings. Therefore, the majority of the people the business pays will also have a very high marginal propensity to consume, so the money will circulate again.

Either some of it goes back to the government, or it goes into the economy, and it goes into the economy, and it repeats and it repeats.

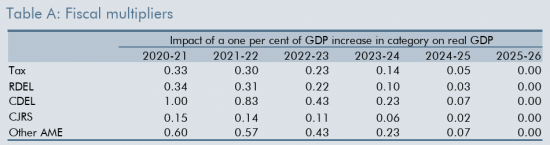

In fact, look at this chart.

This was produced by the government's Office for Budget Responsibility in November 2020, and it is the latest indication that I can find of the multiplier effects that the government uses with regard to each type of expenditure that it undertakes.

Now, the only thing that really matters here with regard to what we are discussing is the bottom line on that chart, which is 'Other AME'. And like everything to do with government finance, this is riddled with jargon. AME stands for 'annually managed expenditure' and that includes things like pensions and benefits, where budgets aren't fixed in advance because the level of claim does depend to some extent on the level of economic activity in the economy.

So this is what we are looking at when we talk about the multiplier effects on benefit payments. And as you'll see, the pattern extends over five years.

In other words, in the first year in which money is spent, the Office for Budget Responsibility thinks that for every pound spent out in the first year, after that pound is spent, GDP will increase by 60p.

In the second year, it'll increase by 57p, and then in the year after that, by 43p, and then in the year after that, by 23p, and finally, five years after the initial spend, there will still be a residual effect of 7p.

In fact, for every one pound spent in the first year, a total of £1.90 will be recovered.

In other words, this is a strong, positive multiplier effect. In fact, if the government spends a pound on increasing benefit payments, £1.90 will come back, albeit over time, but GDP will increase. The benefits will flow through to the economy, and the government will therefore be able to recover tax as a consequence, directly and indirectly, as a result of this spend.

Now in practice, this, I believe, is understated, and there are two reasons for saying that.

Firstly, that is because this is an aggregate multiplier and I suspect that the multiplier effect with regard to payments of benefits to those on low pay is much higher than this because those on low pay have such a high marginal propensity to consume that I would expect these figures to be anything up to 50% higher than this.

Secondly, we also know that everyone associated with the UK Treasury has always historically understated multiplier effects, and there's a lot of academic research to suggest that is the case. Even the International Monetary Fund did once upon a time criticise the UK government for forecasting with too low an estimated multiplier effect.

So, I very much doubt that the yield from payment in this case is £1.90. I would strongly suspect that it's over £3, in fact. And if that yield is £3, and the overall rate of taxation in the UK economy is over a third, which it is, then £3 of GDP growth multiplied by an aggregate tax rate of around 35% will mean that the government will collect back in tax more than it's spent on benefits in the first place.

So, spending on removing the two-child cap will actually pay for itself. That's my critical point. We don't need to be mean, because being mean actually reduces growth and reduces overall net government finances. Not only is it petty, because people are in need and poverty, and children are suffering, and that is something that any government, let alone a Labour government, should not tolerate, but actually spending in this area will increase government revenues in the long term.

My argument is, frankly, one that every government minister should know, every journalist should know, every single commentator should know, because if as is likely this multiplier effect is as big as three, and it won't be less than the 1.9 that the OBR is using in aggregate for such rates, then there is no excuse for not removing the two child benefits cap now.

Come on, Rachel Reeves, just do it.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

Could you add the chart please

Done

It’s also possible to estimate many non-financial returns to government – and often express these in financial terms too, enabling a more realistic cost-benefit analysis (social return on investment). For example, it’s known that lifting children out of poverty will have lifelong health benefits for them – but this means future government savings on the NHS, sick pay, etc. We can estimate these by looking at historical health differences across income levels. Children kept out of poverty also tend to be less demanding on other services, such as policing and justice, to have higher lifetime incomes (and tax payments), etc, etc…

I’m not an economist, but I do know a bad calculator when I see one—and Rachel Reeves appears to be using one last updated during the Ice Age.

How else to explain Labour’s refusal to scrap the two-child benefit cap, unfreeze basic welfare payments, or even decisively restore the Winter Fuel Allowance—policies that would not only lift people out of poverty but, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility, actually grow the economy?

Yes, Reeves has U-turned on the Winter Fuel Allowance, but let’s be honest: it’s the kind of U-turn that leaves the car still parked halfway over the line. After outrage from pensioner groups, internal party backlash, and the looming electoral threat of looking like austerity in drag, Keir Starmer was wheeled out to announce a climbdown. But the details? Vague. The delivery? Unconvincing. And the intention? Let’s say it felt less like moral conviction and more like panic with a press release.

This pattern is becoming clear. Labour—no longer the opposition, but the government-in-waiting—seems terrified of power. Or worse: they’ve mistaken responsibility for meanness. Reeves presents herself as a sensible steward of the economy, but her version of sensibility involves refusing to spend money on the people who need it most—even when doing so would stimulate growth, reduce inequality, and pay for itself.

What’s baffling is that this isn’t even some radical socialist dream. We’re talking about basic Keynesian economics. When you give money to those on the lowest incomes—whether through child benefits or winter fuel support—it doesn’t vanish into a black hole. It goes straight into the economy. These households don’t save. They can’t. They spend every penny—on food, heating, rent, kids’ shoes. That money then circulates: shops earn more, VAT is paid, wages go up, taxes come back to government. The fiscal multiplier effect is real, well-documented, and—according to the OBR—makes this kind of spending one of the most effective economic tools the government has.

And yet, Reeves and Labour are still acting like they’re waiting for a note from the headteacher at the Institute for Fiscal Studies before doing anything remotely redistributive.

Here’s a better way forward:

Scrap the two-child benefit cap – Start with a phased approach if you must, targeting low-income working families or households with disabled children. But for heaven’s sake, stop punishing children for being born third.

Deliver a clear and complete reinstatement of the Winter Fuel Allowance – Means-testing may sound clever, but in practice it penalises pensioners just above the line who still can’t afford to heat their homes. Keep it universal or at least transparent.

Unfreeze and properly index benefits – What kind of government brags about “growth” while letting inflation erode the incomes of the poorest?

Drop the fetish for ‘hard choices’ – Austerity isn’t moral, and it certainly isn’t good economics. Spending on those with the highest marginal propensity to consume is one of the least hard choices any government can make.

Ultimately, Labour needs to ask itself: does it want to be remembered as the party that won power, or the party that did something with it? Because right now, it feels like Reeves is so desperate to be seen as “credible” that she’s afraid of actually making a difference.

This country doesn’t need more fiscal navel-gazing. It needs a government that understands poverty isn’t a spreadsheet error—it’s a political choice. And if Labour won’t choose to fix it, what exactly are we voting them in for?

Come on, Rachel. You U-turned once. Now make it count.

“Why is Rachel Reeves refusing to remove the two-child cap on benefit payments”

Because she does not want to, is the brutal answer. All your arguments are correct and logical, but are meaningless to someone who is part of the British establishment.

Britain is set up as a hierarchical society, and has been for close to 1000 years. Reeves is part of that system and will not change it. It includes all the political parties, media, mainstream Journalists, NGOs, charities, etc. – the whole British system. The establishment needs the poor, the sick and disabled to keep those just above, in line. The idea of relieving poverty for anyone, goes against all they stand for.

Nothing significant, will change until that system of Government, is consigned to history

may I put my oar in and ask also for one other thing that has been forgotten, namely bring back a national Council Tax Benefit scheme.

Chart is missing

Added

I think we can all sense that this one can be pushed over the line. As well as the economic argument that you’ve made so powerfully, maybe it’s also time to start stressing the political benefits for the Government of removing the cap. Here are some thoughts.

Moral Leadership: Lifting the cap would help the government to be seen as compassionate, ethical, and guided by strong social values.

Core Base Engagement: It would unify Labour MPs and supporters, particularly those who feel strongly about ending austerity and tackling child poverty.

Centrist Appeal: The policy would resonate with middle-income and family-focused voters who value fairness and support for working families.

Economic Framing: Removing the cap can be framed as a long-term investment in children’s development, which supports economic growth and productivity.

Political Strategy: It would help Labour outflank rival parties — including the Greens, Lib Dems, and Reform UK — who have also pledged to scrap the cap. It also reduces the ability of opponents to criticise Labour for lacking substantive policy on poverty.

Media & NGO Support: The move would likely win strong praise from children’s charities, NGOs, faith groups, and socially focused think tanks. Much of the media, especially centre-left and public service outlets, would view it favourably.

International Reputation: Ending the cap would align the UK with international standards on children’s rights and social policy, helping to repair Britain’s global reputation on human development issues.

In an information rich society, it is hard to justify such ignorance on behalf of Reeves and her colleagues.

Indeed, they are just blinkered by ‘idiotology’.

You only have to think about how real money – coinage – gets circulated on a daily basis to understand that this is all about the journey of money in the real economy – from one person to another, to be used over and over again (paying some tax as well at each turn, until it is taxed out of existence – unless you are rich of course or it is saved and out of circulation of which there is not enough of that either). The same goes for electronic money too I wager.

To me, Reeves typifies the total lack of imagination in fiscal policy and state intervention and frankly this sort testicular material is really getting on my tits.

“In fact, look at this chart.”

The chart is not in my copy.

Great artical. I look forward to your regular contributors they make very good points.

Added now.

Apologies…

Your maths and your assumptions are correct.

You clearly “understand the numbers”.

But she doesn’t “just do it”.

Why?

As I have said elsewhere, because of a moral crisis at the heart of government, the only calculations being done are not short, medium or long term economic ones, but very short term psephological ones, and those calculations (about polls, headlines and election forecasts) are done by Morgan McSweeney in Downing St., not by Rachel Reeves in the Treasury.

Those calculations do not even remotely consider the welfare of suffering vulnerable people, or the stability of our society, because those making them are morally myopic, incapable of considering the welfare of others, blind and deaf to real need, or the logic of attending to it.

Morgan McSweeney juggles with one metric only, the relative standing at any single point in time, of Keir Starmer and Nigel Fa***e, of Labour (so called) and Reform UK.

Both McSweeney and Fa***e are economically illiterate and incompetent. But Fa***e is far more nimble politically than McSweeney, and will consistently outmanouevre Labour. Fa***e doesn’t need to worry about economics or logic, he can dodge to the left or the right, he can contradict himself, he will win every time, he IS “agile”, McSweeney just knows “agile” as a meaningless slogan, hung round the neck of the least agile PM we’ve had in decades.

3 signs of hope though…

1 – the economic truths are gradually making headway. KUTGW!

2 – McSweeney’s star is fading. Once SPADS become the story, they are finished. McSweeney is now the story.

3 – Reform are now governing (locally). Fa***e now has a party machine he has to manage. He couldn’t manage 5 MPs without chaos, and he certainly won’t cope with managing 600 chaotic councillors. He must be harried, challenged, questioned, exposed, without mercy, with the hard reality of local government, to expose him and his party gor the dangerous incompetent nasty windbags that they are. He will fall. Then, we have to have something better to put in his place. “Ah, there’s the rub” – but at least that is getting some attention now as well.

Please correct me if I’m wrong, but in regard to the W.F.P didn’t Starmer and Reeves say that they, “Would look at that payment and see if it could be restored to “more” pensioners”. Apart from the fact that both are imbecilic liars, is this another futile attempt by the Labour Party to try to head off Reform? It look very much to me like another fudge, that the original concept will never be restored, and that any payment will probably be means tested, if it ever happens.

It was more of the usual word salad.

Robert Reichs post on the reemergence of social darwinism… Leads me to think… No, it confirms my thinking that the UK is headed in exactly the same direction.

I have not read it as yet, but will do before the day is out

It’s funny how all this public spending allegedly ‘pays for itself’, yet historically all this public spending has led to bigger and bigger debt, not bigger and bigger revenues (and hence lower debt).

Your claims don’t seem to be supported by the evidence!

Oh dear, what complete drivel.

Growth has significantly increased private wealth, which people want to deposit with the government, which is exactly what treasury bonds represent. They are simply savings accounts for the growing wealth of some in the UK and elsewhere.

What you are saying doesn’t make sense.

If the treasury bonds were ‘simply’ savings accounts, then If the government didn’t spend the cash deposited, there would be mountains of cash to balance the bonds and hence no debt while If they do spend the cash ( which they obviously do) then according to you the government should be getting back even more than they spend in which case they should be sat on even bigger mountains of cash. Which they obviously are not.

Either way, there should be no government. Your theory doesn’t add up.

Go and have a look at the accounts of NS&I before you nmake crass comments here

Even understand how the national debt is calculated – and I suspect very few people ever try to do that – but I have.

There are piles of cash.

And how you reachy your conclusion is beyond comprehension. Are you stupid?

If the government as ‘piles of cash’, why does it need to borrow?

It certainly doesn’t have a £3bn pile of cash.

And why do you have to be rude to anyone who doesn’t agree with you? Mr Parr seems to be making the point that if all government spending results in more coming back to the government, it ought to be fabulously wealthy by now to the point where it certainly wouldn’t need to borrow at all. If that’s how you react to anyone who doesn’t simply accept everything you say as gospel, you’ll have to stick to monologues on your YouTube channel.

I am dismissive of trolls making stupid comments.

Actually, it has hundreds of billions in cash.

It doesn’t borrow. It takes deposits.

You say you ‘genuinely do not understand what Rachel Reeves is doing when she is refusing to either restore the Winter Fuel Allowance for old age pensioners, or remove the two child benefit cap’

As always you are being scrupulously fair-minded. We cannot know for certain what motivates Reeves and Starmer. Yet common sense tells us there are only two possibilities. a) The Labour leadership actually supports the rich. Covertly rather than overtly like the Tories and Reform who openly represent the rich and despise the poor. Reeves attitude to the poor suggests this is indeed a factor. Or b) the rich have the means to exert control over the Labour leadership.

We may reasonably conclude that the reality is a combination of a) and b). Should we not call this out rather than be accused of being ‘the good who do nothing’ when evil inevitably prevails?

I appreciate being accused of being fair.

I also think you may well be right.

“So, a pensioner who gets a £200 winter fuel allowance will spend it.”

True, but it does annoy me that these little “add-ons” exist.

Just pay a decent state pension. One that recognises what people actually need.

We pay the worst state pensions in Europe, and the “man of the people” Nigel Farage seems to have decided that the “Triple Lock”, isn’t sustainable, he will bring back the winter fuel payment if it will buy pensioner votes.

https://inews.co.uk/opinion/pensioners-farages-view-on-triple-lock-3717054

But there is a bigger crisis brewing.

I was reading yesterday about the growing number of retirees, millions of us, that missed out on the property bubble boom. The lifelong renters. Condemned to renting for the rest of their lives.

Private rents. Not really affordable for many. Will the state pension cover it? No. Even now, in many parts of the UK, rent for an average property is more than the monthly state pension. London is a nightmare. And as time, and further guaranteed rental inflation takes place, it will get worse.

What then?

Ticking time bomb time, and something else to add to the housing crisis. Regardless of what the idiots running the show are saying, it’s coming.

Accepted

Sean is absolutely right when he says:

“Nothing significant will change until that system of Government is consigned to history”

The deeper problem is that few recognise this. The way we have always done things is never challenged. The Treasury has been in the ascendant for about 900 years and we can see its habits in the spending negotiations now being leaked almost daily: a battle of wills that neither Starmer nor Reeves will admit is the wrong way to run a country.

When a nearby local authority amended its Council Tax Support Scheme a year or so ago they increased the maximum benefit from 85 to 100% of the Council Tax.

One of the reasons for doing this was that when they looked at the accounts of benefit recipients who were paying their Council Tax they found that a lot of them were having to use the discretionally assistance schemes for help with other bills.

In the same way families affected by the two child rule must be ending up needing help from elsewhere be it family, food banks etc or ending up with growing levels of debt

The expenses dont go away.

Winston Churchill famously stated, “There is no finer investment for any community than putting milk into babies.” The current crop of politicians seek to take it away

A good quote

Did he really say it?

I have read it too

I think when he was part of the pre-World War One Liberal govt. 1908 free school meals

Apparently Churchill did say:

“There is no finer investment for any community than putting milk into babies,” in a speech on March 21, 1943, according to CVCE.’

To be fair, sayings are often mis-attributed to Churchill. In a book written to advise GCSE History candidates the author advised them to enhance their answers by making up Churchillian quotes ‘because he said so much no examiner could be certain of their authenticity.’

🙂

Neoliberalism overlaps with an ubermensch belief system, where the fittest survive, and so not every child should be helped.

Reeves is a willing handmaiden. Starmer another beneficiary and enabler. The rich and the willing are the chosen ones, their wealth and power are the proof of their merit and superiority.

We should all be very concerned about the dark subtext of Neoliberal outputs, it uses a fantasy economic logic to create an ever growing list of disposables humans, poor children, the disabled, pensioners, Palestinian babies and so on.

Journalists don’t want to know this. They will never make reports based on the multiplier being a factor of economics because they sense that the establishment don’t want this known and that their pieces won’t be published and their careers will suffer. In this they are most probably right. Quite why the establishment are terrified of the reality of economics and the fiction of money (a necessary fiction and one which we probably need to agree upon – at least for the time being) is not always so clear. I suspect many people of this establishment don’t know why they are frightened either. But they probably have an instinct that their own ridiculously unfair purchasing power – in effect first dibs on all the good things of the earth would be impugned.

And so for the sake of cowering venal ignorance the whole world suffers.

No doubt the usual “spook the market” excuse would be trotted out. Even if true, it’d be a good argument for scrapping the ‘full funding rule’, which would appear to be stunting growth of both the economy and human children.

Let the BoE, not Treasury, issue the bonds, and only in quantities needed by the private sector as safe savings and collateral. But then it’d be absurd to call it “the national debt”, and the plutocrats aren’t about to surrender that weapon.

Richard,

Great blog. I really think the multiplier effect is very important in the public realm and people need education on it.

Good comments by all too.

Thanks

Unfortunately, the world was unexcited by it

The best videos we make rarely get the best audiences.

Richard

Richard,

Given that many people genuinely believe borrowing, taxes etc fund spending can we show where this money sits ie which accounts BoE/HMT/etc?

Many times in the past you have shared useful maps of flows to the BoE etc. Maybe you have it already but clearly some people will struggle with the multiplier effect of govt spending and national debt.

Just a thought.

See chapter 16.5 of the Taxing Wealth Report.

[…] Second, their reference to Keynesianism is an oblique hint at multiplier effects. As I explained last week: […]