As the FT has noted today in a free-to-access article, as many as one in 6 10 and 11-year-olds in the UK might now be obese.

As they also note, this is a British problem:

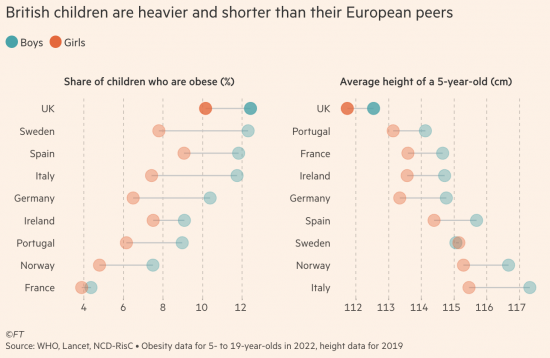

Our children are heavier and shorter than m,any of their European peers.

The explanation appears to be down to diet - and the propensity of ultra-processed food in it.

The proportion of ultra-processed food is a very clear marker for obesity, ill health, diabetes, metabolic disease and many other diseases linked to glucose-induced inflammation, including Alzheimer's. This, then, is an issue throughout life.

What should we do about it in that case? I suggest that the obvious goal is three-fold.

First, we need to appraise the scale of the problem.

Second, we need to decide how to tackle it.

Third, we need a metric for success that might work in the short-term when the problem is long-term in nature.

Others are more expert than I am on the second issue. I will not intrude there, but I will at stages one and three.

Collecting data on this issue is really easy. Our supermarkets have it. They know:

- What they sell

- How ultra-processed it is

- Where they sell it

- And, who they sell it to via data in loyalty card schemes.

So, all we need is a law that requires them to share this readily available information, and all the data that is required to appraise the scale of this problem would be available. That data would need appraisal, but once it exists, that's the easy bit. The problem is always about getting the right data. That problem I have solved.

That then suggests the required metric for appraisal of progress. Quite simply, the proportion of ultra-processed food that is sold must be reduced. Targets can be set. Progress can very easily be appraised. This really would not be difficult. People would be better off, as would society be, as would the NHS be in the longer-term as we would live healthier lives.

There is, almost certainly, no change that could have a greater impact on demand for NHS services than reducing the consumption of ultra-processed food. I have suggested how to set up a system to appraise this. Now, others need to agree on:

- What to tax

- How to change packaging

- How to change advertising

- How to compensate those who might need more money, space and other resources to manage non-processed food

- How to provide universal free school meals

- And other related programmes.

Would that really be that hard? I suggest not. I even suggest it could be self-funding for those who think such things matter (even though they don't).

What are the objections?

And why would a politician say no?

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

There are links to this blog's glossary in the above post that explain technical terms used in it. Follow them for more explanations.

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Buy me a coffee!

Buy me a coffee!

I’ve often thought supermarkets should be making more data anva to their customers. They could provide monthly summaries about

ultra processed foods, number of calories and environmental impact of our purchases. If they identified the top ten most harmful purchases, maybe suggested a less harmful alternative, consumers would be able to make better choices.

Agreed

First the problem is how to get round the Personally Identifiable data issue, generally by aggregation, but national or regional aggregation hide the problem. My feeling is we could use no political ( i.e. not established spatial groupings, like wards, counties, or regions) instead using tessalated shapes based on the loyalty cards registered postcode. By aggregating to these areas the whole population is covered but personal identification is difficult, further security could be made by following the Census rules for publication.

That geographic distribution of food purchase could then be combined with census data for the population demographic detail, demonstrating both the size and location of the need. This given funding local solutions to the particular problems could be identified, tried and if working enhanced and copied elsewhere, though they might not work, as local history and culture are crucial.

Don’t expect rapid change, but when it does it can be locally dramatic.

But it’s dependant on trusting letting local leaders to emerge, something current central political leaders are terrified of happening!

Yes,

Why not educate people into eating better and healthier then, as more people go for those options, lowering the price through economy of scale.

Supermarkets ought to support a “just transition” to healthy eating.

I quite like this:

“What school lunches look like around the world” (2020)

https://www.amieducation.com/news/what-school-lunches-look-like-around-the-world

“15 School Lunches From Around The World” (2021)

https://medium.com/yaylunch/15-school-lunches-from-around-the-world-22ed3d14e613

Look at America’s school meal, 2 notable things jump out.

i, The US school meal is predominantly carbohydrate (bad: at its highest carbs should constitute 40-50pc of the calories in a balanced meal) – where’s the amino-acid ‘protein’ and fat that growing children need,

ii, it includes MILK (for the much-needed fat and protein). No Thatcher milk snatching there then?

ALSO the US has publicly funded ‘n’ run post offices, mail, rail, water as well as school-provided MILK. Foreign country – Mrs T, John Major, Vince Cable, et al obviously didn’t manage to persuade the US to “Chicago school” themselves.

We don’t need carbs.

We are addicted to them. I admit I can’t give them up.

MMMM, maybe true Richard, but not practical for many people or society. Carbs are actually a highly efficient food source – it’s just that most people consume far too much of them far too often. I was carb-free for about 3-4 months and mostly found it very beneficial, but several (animal and human) studies have shown extremely negative effects at both a cellular (ATP) level and metabolic, physical energy level from total carb avoidance over 6 months.

The Irish (joke) reply to the person asking for directions, “I wouldn’t start from here” might be relevant. People should gradually and controllably reduce their carb intake and – as some keto diet enthusiasts already claim – you might be able (eventually) to totally reduce your carb intake to nothing at low/no cost. Me, I wouldn’t want to – many valuable nutrients can be obtained from unprocessed carbohydrates.

I think low carb is wise

I doubt I could be keto

My wife thrives on it, though

Richard

Thank you for posting this.

My first response is to offer that there does exist a huge data set on this nutrition / eating habiits subject and it is held by trustworthy scientists (with a minor commercial aspect).

https://zoe.com/our-studies

My second point is the really hard one, getting people to see an existing threat and make changes to their dietary & other coexistent habits to preemptively avoid difficulty or tragedy ahead.

Climate trajedies & covid pandemic already show how inflexible people can be to avoiding threats, we ignore them as low priorities, even though experts show us clearly that huge consequences will likely happen from not making changes.

But many medias make the mindless rants of the lowest minds into the prominent voices most heard!

Add to that the lobbying lusts of multinationals with their client politicians guarding their wealth streams, you then have a recipe for painful consequences that hurt many.

When will real experts be properly respected?

I do not think the Zoe data is reliable. The subscribers are very unrepresentative of society as a whole. It’s a start, but not good enough, I would suggest, and may understate the problem.

And the answer to the second question is the government has to start doing this. It only respects bankers right now. That is not the same.

There is one big mistake the writer made and that is the need to compensate those who consume processed foods none processed foods are more expensive.

What is necessary is to teach the population how to cook food not how to reheat.

I have not made that mistake. I discuss it, often, making clear this policy could be self funding from NHS savings.

Good, extensive thought-piece Richard. “And why would a politician say no?”

In opposition, Wes Streeting SEEMED to say many right things A positive step forward as Shadow Health Secretary commits to stricter regulations on the food industry, but it’s a smoke/mirrors job of the highest order: Streeting might be hinting that he’d flex governmental muscle by alluding to control and command through the ‘R’ word, regulation, BUT he made sure that the food conglomerates didn’t panick by using a plethora of phrases like “collaborative ventures/initiatives/investigations”, etc.

I’m horrified to be informed by people who work in the food industry, or, more often, with the health effects of UPF that UK regulators, particularly the FSA, are being very Lilly-livered on UPF – unlike their US counterpart – by which I mean far too much of this report addresses definitions, methodology and interaction with the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) to ” conduct research on ultra-processed foods”

It might be the culture as much as the reprobatic (?) nature of some politicians that’s making the UK a world-leader in UPF-caused obesity.

https://www.food.gov.uk/safety-hygiene/ultra-processed-foods

Um – “preponderance” (sorry) of ultra processed food in our diet?

Curse, in my opinion. This is imposed.

There is less inequality between boys and girls in the UK, so there is that.

I find it hard to believe that Swedish girls are as tall as Swedish boys by aged 5 and think there must be a data or measurement problem.

Why?

In all the other countries 5 year old girls are 1cm or more shorter than boys.

There are no examples of countries where the difference is 0.5cm or less, and Sweden pops up with girls very slightly taller than boys.

This is called an outlier in the data and one should be wary of trusting such.

So? Are you dismissing the whole thing fur that?

What is your point?

A well known example of bad data is that obesity rates in the UK almost halve between aged 15 and aged 16 when the adult measure of BMI takes over from the previous height and weight tables used to calculate child obesity.

And yet the graphs used by the FT state “5 to 19” year olds. Legally people are not regarded as children for the last two years of that range. And as I said, in the UK, the way obesity is measured changes for the two years before that.

We should not base public policy on data like this.

Ok, what data should we use, and is it available.

What would the gain be?

No, Mr Delphine I was not straw manning. I confess that I may well have had some difficulty understanding your point, but I would suggest that taking four short, ill-drafted comments to explain what you meant to the only two readers moved to respond, I think is a fair explanation of the underlying problem.

Mr Delphine,

I confess I am sceptical of your reliance on BMI. I shall not labour the point, but present this excerpt from the TC Chan Scool of Public Health, Harvard University in December, 2022, arguing there is growing concern that:

“BMI—a formula that uses height and weight to measure body fat—is a ‘flawed, crude, archaic and overrated proxy for health.” Those opposed to its continued use argue that it was developed based on white males and has little validity for other racial and ethnic groups, and that it is sometimes used to deny certain people joint replacements and other surgeries. Experts have also pointed out that BMI fails to take into account factors such as how much fat versus muscle a patient has, the distribution of fat in their body (typically, fat around the waist increases disease risk more than fat in other places), and their metabolic health.

……. [Bryn] Austin and … Tracy Richmond of Harvard Medical School [have] noted that, “in many of the instances in which BMI is assessed in medical settings, the information is not pertinent to medical decision making and often not even used. Thus, BMI assessment may be causing risk (e.g. loss of trust, delayed care) while providing minimal to no benefit. This raises a reasonable question: What purpose is served by continued collection of these data even as the very practice of BMI assessment itself negatively affects healthcare access and quality of care?”.

I do not have medical expertise, but I do know that people in the field have suggested waist measurement is far more important than BMI (a good pointer for older people eho have put on weight, is their comparative, typical waist measurement when younger adults). I leave you to defend your case.

Your case is well founded, John.

I wasn’t being reliant on BMI John. Straw manning is what you just did. I was pointing out an outlier in the data from the FT, and then followed up by pointing out inconsistencies in the UK data due to the switch in measurement protocol from aged 15 to 16.

If someone wants to rely on it for personal use,they can go ahead, but we should not use it to inform public policy.

Your last paragraph supports my point, for which I thank you.

I have three points to make.

Pedantry is rarely helpful.

Dismissing evidence on the basis of nit-picking usually reveals another agenda.

Public policy is always based on judgement. If Tunis nit, it is always bad, and is probably hiding its agenda.

I did a minor rant on LinkedIn yesterday about the growing habit for “food” manufacturers to use artificial sweeteners in place of sugars. In the example I gave, Sainsbury’s standard diet lemonade contains them -unsurprisingly- but shockingly so does the non-diet version.

I suspect this is so they can make the RAG boxes on the front of the bottle look more appealing, rather than avoiding the sugar tax as I initially thought.

It is an example of how people driven by profit are working their way around the metrics and staying one micrometer to the right side of legal, while not being as transparent as consumers need.

So to your stage three and identifying the right metric; we have to consider the escape routes that “food” manufacturers might use, be ready to observe them finding ones we’ve missed, and close them down quickly.

Robert Lustig points to Scandinavian studies which show that ‘sweetness’ primes the body to get ready to metabolize the incoming sugar rush, and it makes no difference whether the sweetness is natural or artificial in origin. However, if there is no following sugar rush, appetite is stimulated so that the released insulin has something to do. In short, artificial sweeteners are just as bad, if not worse.

It’s encouraging to see healthy school meals being served, thanks mostly to Jamie Oliver’s campaign.

The highly successful sugar tax may provide a template for tackling the growing scourge of ultra-processed foods. We know from bitter experience that no “voluntary codes” will make the slightest difference to the food manufacturers. They will continue to churn out these unhealthy foods for the simple reason that they are highly profitable, so the government needs to act to make them a lot less profitable and ignore the predictable “nanny state” whinging from the usual suspects on the libertarian right.

They did voluntarily restrain salt.

But I think there no chance they will replicate that with sugar.

They were willing to restrain salt as salt producers are not a wealthy well organised lobby.

The same happened with CFC’s and Lead in Petrol, old technology no longer patented, obviously harmful.

There were clearly opportunities in replacing them

Funnily enough the same scientist was involved in creating both but hey ho………..

Thanks Richard UPF is a real curse on our society

I think some foods should just be banned from being made in a UPF way when there are other “old school ways” of creating them

For example many store-bought versions of ice cream are filled with gums, emulsifiers, and other additives. These not only prevent the dessert from turning into a puddle too quickly but also allow for a wider distribution, a longer shelf life, and a reduced reliance on pricier natural ingredients like genuine full-fat dairy.

Another easy target would be a ban on all seed oils and seed additives these really are prevalent think vegetable oils, supermarket bread, and lots of cereals.

lastly you ask “What are the objections?

And why would a politician say no?”

The giant corporations that produce the UPF’s would lose money

and the giant Pharmacutical corporations that bung wes Streeting and his ilk want to sell us the cures to these foods.

and the politicians that are bribed by those corporations with legal donations and promises of future employment wont like it, it is after all what they went into politics for

I read a very interesting article on cooking oils which may be related to our poor diets in the UK. Palm oils come out pretty badly and are in a lot of ultra processed foods:

https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg26435160-100-the-complete-guide-to-cooking-oils-and-how-they-affect-your-health/

It also got me thinking about the way we prepare food, and the popularity of air fryers – how does air fried food compared to the healthiest and least healthy cooking oils?

Could subsidies on fresh vegetables to bring the price closer, or lower, than UPFs be worth exploring?

Until recently these oils were praised

Could that be manufactured praise, quite literally?

Indeed, seed oils (vegetable oil) may not be the healthy option we once thought it was.

“How seed oils took over our diet and what it means for our health” by Nina Teicholz (December 12, 2024)

https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/3259080/seed-oils-took-over-diet

Nina is a not a reliable person. Seed oils better than butter and lard, but best to avoid both

Completely wrong.

Butter and lard arte fine – we need those fats.

We do not need seed oils.

Richard, this is a great practical initiative….

Looking at the charts, I was struck by the data from France. The narrow gap between boys and girls is itself interesting, let alone their position at the bottom of the obesity chart. Since I’ve been here I have made some broader observations about French food culture, which I thought I’d share here. I do stress that these are just street observations, although I am used to working with data, have lived in many parts of the world, and am fairly observant.

1. The classic ‘French diet’ is quite different to that in both the Anglo-Saxon and Mediterranean countries, with big emphasis on rich, fatty animal/dairy based items – lots of cheese, cream, butter and potted meats, pates and sausage. Veg is fresh, seasonal, and far more varied than in the UK.

2. Supermarkets sell – FOOD! Even the big chains have large veg sections, with individual and well stocked fish counters, cheese counters, and meat counters. Chocolate and biscuits are creeping forward but crisps and snacks are shelved at the back adjacent to the wine. All supermarkets have a significant ‘Bio’ section and there are at least two large chains of organic supermarket, one of which is a co-operative.

3. Every village has its weekly food market and they don’t sell snacks. There is usually a sizeable proportion of local and small scale producers. Likewise every village has its boulangerie, open pretty much every morning (I gather this dates back to Napoleonic regulation and the desire to avoid bread riots).

4. Although high-value food is rich, it is bounded by cultural norms and served in small quantities – piling a plate with meat, cream, cheese etc is seen as decadent Anglo-Saxon self-indulgence, contrary to French self-respect and chic. Patisserie is highly ornate, luscious, and clearly a designated part of a meal rather than a snack. Helping oneself to the centre end of the wedge of lush creamy cheese is a cardinal sin.

5. ‘Frenchness’ is associated with self-discipline and socially conventional behaviour in public. I get the impression that Le Snacking is frowned upon, especially with regard to well brought up French children. French adults are notably slimmer than their British counterparts and I have never seen anyone eat in the street.

6. Everything closes for two hours in the middle of the day for the main meal (arg). Lunch is eaten en famille, but fortunately I think the alcohol content has been curtailed since the ‘sixties. I’m not living with children so I’m not sure what the school lunch situation is – maybe someone might enlighten me?

5. I have noticed an intruiging number of very petit/e people, slim and around the 5ft/1.5 height mark. Most I would say over 50 and living in more rural areas. I am tempted to link this to extreme food scarcity during the Occupation when it was all shipped off to Germany (but other views would be interesting). Very few individuals are old enough to have been directly affected even as children, especially as rationing was not a thing and did not extend post war and I’m guessing that most food was produced locally at that time so would have been more widely available in the immediate aftermath (again, I’m speculating and open to enlightenment should anyone know better). This all points to an epi-genetic or at least some intergenerational effect, which I suspect is both physical and cultural.

6.The food ecosystem clearly extends outwards into the political sphere – the specific appeals of the far Right especially with regard to regulation (which I’m sensing is as much to do with rule-making and control of commercial supply chains from the centre vs the displacement of rural power bases, than with any abstract political ideology); the collective power of farmers and their willingness to ‘tractor-up’ and take direct action; the greater mainstreaming of green/eco initiatives; effective grassroots organisation by all sides through local rural networks in villages/communes/markets; the association of good food with French national pride and identity.

I do stress that these are simply local off-the-cuff observations, and I’d welcome greater elaboration. But it’s a debate worth having and examples from elsewhere can lead to new ways of doing things. Just don’t get me started on Japan …

Thanks

Fantastic observations and thoughts, Joanna. Re your point ‘2’ and my experience with supermarket vegies, two thoughts:

– ever since the over-orchestrated coronavirus ’emergency’, the freshness or shelf life of ostensibly ‘fresh’ vegetables has decreased/reduced noticeably. Only if I pay top whack for me carrots and buy them at Waitrose do they not become pliable (literally, they can be doubled-over on themselves, which shouldn’t be possible with carrots) within 5 days. Sainsbury’s unbagged carrots are bad for this, and all supermarkets I use (Aldi, Sainsbury’s, Waitrose) for polythene-bagged carrots rarely last longer than 5 days and develop a thick black colour on their surface. What’s going on – could they be irradiating them and forgetting to tell us, I bet that wouldn’t happen in France?

– prices: Across the last 15 years, my carrots have increased from c 08 – 12p per kilo to (currently) 69 -95p per kilo (organic is more). Is, as I suspect, there maybe a particularly aggressive Futures market for root vegetables, or are the major supermarkets just acting like cartels? (As with milk, I bet farmers are not seeing much of this retail increase). Surprisingly the pandemic disruption, energy price increase and reported labour shortages since we left the EU haven’t worsened the rates of increase since 2020. Do you know, Richard, is there a futures market at play on root vegetables in the UK?

That reads like a rant? I understand if you choose not to submit it Richard, but supermarket ethics and vegetables are causing me a lot of agitation recently …

Rant permitted….

Richard – the paragraph breaks seem to have disappeared from my post! I will attempt to re-submit it 🙂

They were there

They just look as though they are lost

Thank you for this. A notable addition to your valuable observations and analysis is in the relationship between poverty/deprivation and childhood obesity.

Please see a table of this in the report here – https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2022-part-2/childrens-overweight-and-obesity

So many strong ideas … but perhaps some tendency to bow to the strength of food manufacturers.

As you write, Richard: What to tax?

You have pointed us to the annual costs of UPF to the UK in terms of health and social care and the impact on the economy and productivity (£260 billion), as detailed by Professor Tim Jackson.

(https://www.independent.co.uk/business/unhealthy-food-is-costing-uk-more-than-ps260bn-per-year-report-says-b2648284.html).

It appears to be way past time for the public to be demanding that private profits can no longer be paid for from the public purse. The UPF pressure engine is just starting to rev up.

But another pressure engine along the same lines – privatisation of water – is running at higher speed.

(https://www.theguardian.com/business/2024/oct/16/water-industry-public-ownership-citizens-assembly-labour-bill)

The main problem is that there is no consensus that UPF as a category has a meaningful impact on health. All data comparing UPF with processed foods are from observational studies which rely on data that does usually not allow to identify UPF reliably. This is one reason why neither the UK nor the US nor the Nordic countries advise against UPF consumption.

The difficulty in estimating intake means that even for supermarkets, it would be virtually impossible to distinguish between NOVA 3 and NOVA 4. Would – for example – chicory root extract make a good UPF? Would high speed mixing make bread UPF?

Regarding the intake of children: due to the difficulties of estimating UPF intake, UK bread is usually assumed to be always UPF – so a homemade sandwich as packed lunch will always be classed as UPF. Likewise fish fingers, even if they are generally considered to be a healthy and sustainable source of fish.

There is a wealth of data for nutrient composition and its effect on health. Why should we change this approach to something popular but without much evidence?

A reply to this comment will be posted on the blog.

I moved to Nordic region over 30 years ago. The running joke here is how to spot a Brit on the beach on summer holidays. They are always short, fat and a pale white colour. Two days later they are burnt bright red. Sums up the terminal decline the UK seems to be heading for…

1806, Britain’s naval blockade cuts France off from its sugarcane supply.

Sugar became scarce. Prices soared.

And riots erupted. Not over bread, but sugar.

I kid you not.

[…] This post was written in response to a comment on this blogin response to a comment on this blog. […]