This paper was published last week:

The paper has the following abstract:

This paper constitutes a first detailed institutional analysis of the UK Government's expenditure, revenue collection and debt issuance processes. We find, first, that the UK Government creates new money and purchasing power when it undertakes expenditure, rather than spending being financed by taxation from, or debt issuance to, the private sector. The spending process is initiated by the government drawing on a sovereign line of credit from the core legal and accounting structure known as the Consolidated Fund (CF). Under directions from the UK finance ministry, the Bank of England debits the CF's account at the Bank and credits other accounts at the Bank held by government entities; a practice mandated in law. This creates new public deposits which are used to settle spending by government departments into the economy via the commercial banking sector. Parliament, rather than the Treasury or central bank, is the sole authority under which expenditures from the Consolidated Fund arise. Revenue collection, including taxation, involves the reverse process, crediting the CF's account at the Bank. With regard to debt issuance, under the current conditions of excess reserve liquidity, the function of debt issuance is best understood as a way of providing safe assets and a reliable source of collateral to the non-bank private sector, insofar as these are not withdrawn by the state via quantitative easing by the Bank of England. The findings support neo-chartalist accounts of the workings of sovereign currency-issuing nations and provide additional institutional detail regarding the apex of the monetary hierarchy in the UK case. The findings also suggest recent debates in the UK around monetary financing and central bank independence need to be reconsidered given the central role of the Consolidated Fund.

The paper is, in essence, a reworking of a paper published by some of these authors last year for the Gower Initiative on Modern Money, with less double entry.

The merit of the paper is that it works through the legal mechanics of government spending in the UK in detail and show that unambiguously spending has to come before tax or borrowing. It is as simple as that.

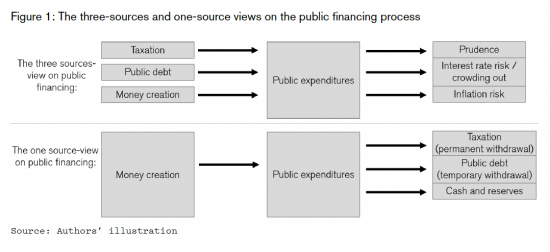

As a result the authors draw this successful diagram:

They reject the top model as they say this simply does not happen in the UK and promote the bottom model, which they show is exactly what does happen, even on a daily basis in the UK.

Other diagrams in the paper are not as successful, in my opinion, but this is the key idea, and one that will be entirely familiar to readers here.

As the authors conclude:

At the heart of the government spending mechanism is the Common Fund. This is best understood as a line of sovereign credit that the government, via permission from Parliament, draws on, backed solely by the ability to raise taxes in the future. When spending occurs, Exchequer credits are allocated to the Government Banking Service and shifted on to the Bank of England's balance sheet as public deposits. This, in turn, creates deposits at the commercial bank accounts of government departments, thereby enabling spending. The process is legally mandated and cannot be challenged by the central bank or any other government department. We find the one-source view on public spending (Figure 1) reflects institutional reality, where all spending is financed by money creation.

They continue:

The primary economic function of government debt issuance, in the context of the ‘floor' reserve management system that the UK has today, is to support the desire of the non-bank financial sector for a secure store value and source of collateral. However, the BoE's purchases of gilts withdraws the bonds back on to a public sector balance sheet and thus partly neutralises this function. This inconsistency among the DMO and the BoE in terms of government debt dynamics suggests that the UK monetary system could be simplified.

Their last word is:

Ultimately, from an institutional and economic perspective, there is a magic money tree, though it should be understood as a legislative money tree represented by the CF with recourse to Parliament. The true limits on the Government's spending power are the productive capacity of the UK economy, the political will of Government and the consent of Parliament.

I suggest this is a paper worth reading.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Wonderful – let’s make sure it gets sent to all our MPs.

I love that second diagram.

Thank you Richard!

It’s a great paper, but a shame that it will remain ignored by most economists and the media.

The earlier Gower paper (tome) has informed the economic policies of the Breakthrough Party (minifesto coming soon)

Only in principle, Richard. There have been times during this period when the currency was tied to gold, one way or another. But certainly since 1971, there has been a magic money tree without qualification. Even when it has been the case with no impediments, the Treasury has fought it tooth and nail. They are, effectively, misers.

No, there was a magic money tree before that

The golds standard was simply there in an attempt to stip it being used

That’s something very different from what you are suggesting

I think we need to acknowledge a long and deep war about the nature of Government money and who should benefit from it.

This war has been about who will get this money and who won’t and who will profit from it and who will be profited from instead.

For far too long, the rich, corporations and lately criminals have been able to benefit from this war and have been winning.

It does not have to be this way and that is the story that we must keep telling.

So it is a war about a resource – like many wars – the resource being money and the money resource being coveted by a few major bad actors in the economy.

And there is also a concerted conspiracy in my view to keep people knowing the truth about sovereign money that can only be described as anti-democratic and monopolistic.

MMT, Money for Nothing and Your Tweets for Free, The Debt Delusion etc.,- all these are efforts to re-democratise money as a resource for all and answering the simple question that Richard once asked:

‘Why is it that we can’t have the money we need?’

All we are asking for surely is a fair distribution of this resource.

I heard Stephanie Kelton speak a wonderful phrase this week:

“A [government] deficit is always good for someone. The question is who.”

Hi Richard,

I’m struggling to understand the CF. What it is and how it operates. The language of the authors is a bit too techincal for me, though I’ve got a ‘sort of’ idea from figure 1. Can you do a plain English version? [Assume I’m a six year old]

Martin

I will work on it….

An invaluable starting point is here:

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1018479/CCS0921300720-001_HMT_Consolidated_Fund_CF_Web_Accessible.pdf

Published through HMSO, 2021 (HC630)

Thank you

Thank You.

I’ll have a look at this, but I fear my knowledge of economic language won’t be up to it. However, if you don’t try, you won’t learn.

Martin

It is worth noting that UCL say this about the CF (and related instruments of financial policy):

“The UK Government maintains several core accounting structures known as the ‘Central Funds’ (Figure 2, top left box). These sit apart from any specific government department and represent the legal entities from which all government expenditure arises, from which all government securities are issued, and to which most government revenue is ultimately surrendered. The Central Funds comprise the Consolidated Fund (CF), the National Loans Fund (NLF), the Contingencies Fund (CCF) and the Exchange Equalisation Account (EEA) (not shown).6 They each provide an accounting framework for distinct aspects of the Government’s financial activities. Despite their central importance to government accounting, the functioning of the Central Funds are not widely known or understood by the general public and rarely, if ever, mentioned by economic or media commentators.” (p.9)

JSW, It’s rarely understood by these who should – accountants. Especially these who did Economics degrees! Last week nearly got into a fight with two experts from one of the big 4, who had zero interest in understanding that such an account event exists (CF) – they insist that only taxes pay for government spend and the rest is borrowed… the MMT is their easy put down … I have promised them a further education when we meet again – so this paper is an absolute godsend. If they are receptive I’ll try sending them to this site to take it up with experts

Keep us informed

The new money created belongs to ‘The People’ and should be allocated democratically and not privately. And allocated where it does most good for ‘The People’.

It is systemic coercion to keep wages down. Money rationing (1984 style) is the to keep the plebs down.

Lower rates for insiders.

UBI removes payday loans and other dodgy private credit schemes.

The money extended by these loans is new money but with private mysteriously collecting a profit?

Banks can be scripted away.

Nationalise the banks.

#newmoney

Well, well: progress. This will take some time to read and consider. My first brief scan suggests some progress, with acknowledgement even of the importance of the ‘hierarchy of money’, and of Minsky and Mehrling (p.5). There are, however “buts”; such as, only two or three references to the dealers ( ‘intermediaries’ or ‘primary dealers’), or of their profits, that I at least quickly found (p,7-8, p.14, p.17). Hmm. So far there appears to me focus on ‘money creation’, but insufficient focus on the peculiarly incestuous nature of the money-distibution system; with commercial banks and dealers being able to use their special access and privileges in the system to act as a money siphon that directs money creation into the hands of the financial sector, where it is accessible to the general public only at several removes from issuance, not as money but as (riskier, less universally transferable) credit, available from financial institutions or their customers (no crisp, new, intermediary-free notes or coins, fresh from the printer, or old notes still circulating free in the digital age). The starkness of the effects of a system in which the sovereign creator of money only provides money through its central bank,in turn through protocols designed exclusively for the profit-seeking ministrations of intermediaries (commercial banks, dealers and privilieged financial institutions), and not open-access, directly to the final user of money – the general public; a predicament that is merely heavily underlined by the effects on ordinary people produced by austerity, and the ‘cost-of-living-crisis’ over now many years, with serious effects. Notice that in the post-Crash solution of making the central bank ‘dealer of last resort’, this has merely strengthened the insiders grip on the system, as a system that is by and for specially privileged, financial sector insiders.

I suspect Parliament’s role as described in the paper is theoretical (economists’ penchant for hopeful abstraction), and has therefore been somewhat exaggerated; since it is blatantly obvious few MPs understand the basic principles.

I read it more generously

It is a partial view, but an important one

I am coming round to your more “generous” view, overall of the paper; my first reading perhaps overlooked the acknowledgement of current arrangements which, “raise questions around the economic efficiency of these operations given the involvement of financial intermediaries (the primary dealers — mainly commercial and investment banks), which profit from handling transactions involving the emission of new government bonds and market-making for the wider financial sector. Of the Government’s £413 billion debt issuance between March 2020 and July 2021, 99.5% was matched by BoE gilt purchases (van Lerven et al. 2021), which implies significant windfall profits for the private intermediaries involved” (p.14). Nevertheless I still do not think this was developed sufficiently; notably because of the real consequences in a ‘cost of living crisis’, ‘of what seems to me an insidious closed banking and dealing system operated by the BofE and Treasury, of privileged insiders that exludes the general public, notably in the digital post-covid age, with much less use of the free (uncaptured) circulation of money (through notes and coin); and which may obstruct Government efforts to ensure money circulates sufficiently among the less well off.

I am however much heartened by an argument from which conclusions flow that are well summarised in this statement, which strikes at conventional wisdom: “theory does not accord with the institutional reality in the UK. In fact, the UK Government is fundamental to the sterling monetary system, including the creation and issuance of monetary instruments and guarantees that underpin the entire public- private monetary framework” (p.19). These institutional realities include the fact that “the UK Government is not exposed to the alleged risks of ‘running out of money’, defaulting on debt obligations, the sentiments of bond markets or a need to reduce levels of government debt below those demanded by the economy. Instead, the functioning of the Exchequer, in particular the daily accounting cycle and trading activities, was developed with the maintenance of monetary policy in mind. Under the current ‘floor regime’, where there is excess liquidity in the market, it would appear the issuance of government debt serves mainly to support secure store-of-value and source-of-collateral functions for the private sector” (p.17). Which may be summed in this neat peroration: “Whatever reforms do or do not take place, it should be made clear that the UK Government spends by issuing new money, destroys money when it taxes, and issues debt securities to provide non-banks with a safe store of value and to affect interest rates in financial markets. Doing so is necessary to improve public discourse and discussion in economic policy and research communities, and would enhance political accountability and democratic scrutiny of macroeconomic policy” (p.20).

Oh, and they rather cut the feet from the Bank ‘independence’ conventional wisdom (Para.5.2, pp.17-19): “The BoE is never independent in the sense that it can decide not to facilitate public expenditure.” (p.19). Ouch!

Thanks

Definite progress.

I’m afraid people will read “backed solely by the ability to raise taxes in the future” and think ‘Ah-ha, so it is tax payers’ money and we do have to pay it back!’

Then they should read a bit more of it

The ability to raise taxes is actually the demonstrable proof that the issuer of the currency is sovereign. It is the stamp of irrefutable authority; and that is absolutely fundamental, and never noticed because it is so big it envelopes anderstanding and thus remains hidden from general view.

Agreed

Like so many, I am trying to get my head around MMT. However, I am approaching this from a background of little or no formal knowledge in this area. The diagram is very helpful, and I shall work my way through the paper.

One question. My understanding, is that governments can ask for as much money for whatever reason to be printed. So my simple view of tax is that it is a lever of control over the amount of cash in the system. It takes it out of circulation permanently?

How does the taxation of wealth fit in? In my rather communitarian political brain, having people with such disparate life experiences is not good. However, those of a more conservative view will tell us we need to invest (and indeed we do) and that the riches of some provide this investment. So, I would tax the rich on the grounds of a fairer society. Is there an MMT reason why such extreme wealth isn’t good for the economy?

Thanks for asking

As I explained in The Joy of Tax there are six reasons to tax:

1) To ratify the value of the currency: this means that by demanding payment of tax in the currency it has to be used for transactions in a jurisdiction;

2) To reclaim the money the government has spent into the economy in fulfilment of its democratic mandate;

3) To redistribute income and wealth;

4) To reprice goods and services;

5) To raise democratic representation – people who pay tax vote;

6) To reorganise the economy i.e. fiscal policy.

When tax does not fund spending – and it does not – it is liberated to do other tasks in the economy – and tackling inequality is one of them

And the reason why extreme wealth is harmful is not exclusive to MMT. Leaving aside the social division, the fact is tat6 the wealthy do not spend all they have and those on lower incomes do. So to boost wealth generally you have to put spending power into the hands of those who will spend and not those who will not