As I have noted previously on this blog, the Corporate Accountability Network, which I direct, is publishing a series of Audit Briefings that discuss the need for audit reform in the UK. The background to this series is noted here.

In a previous briefing, I addressed the question of what accounts are. Amongst the explanations I offered was the suggestion that:

The purpose of accounting is to provide the stakeholders of a reporting entity with financial statements that include relevant, reliable and sufficient information which allow them to make informed decisions.

The obvious follow-up question, in that case, is who are the stakeholders? I address this in a new Audit Briefing, now published.

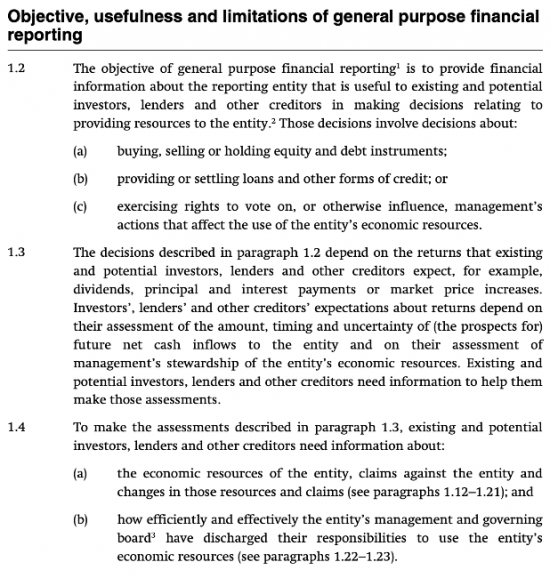

The problem that we face is that international and UK regulators do not agree on who the stakeholders of accounts are. The International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation says in its Conceptual Framework:

Their para 1.4 makes clear who they think the stakeholders of accounts are, and everyone else, they say later in that Framework, are of incidental concern.

The UK's Financial Reporting Council says:

As a result they define a broader range of users, without making clear who they mean. What they do leave is the position unresolved.

The Corporate Accountability Network thinks that this is unacceptable. As a result, the Corporate Accountability Network defines the stakeholders of accounts as being from at least six groups, some of whom will themselves encompass a range of interests:

1. Those who provide capital to the company

This group includes the company's shareholders. It also includes those who provide it with loan capital as well as banks, hire purchase, factoring and leasing companies and those who provide credit card facilities. We believe that these two groups have overlapping but sometimes dissimilar issues in which they are interested when it comes to appraising the activities of any entity. Whilst they constitute one stakeholder group we highlight their differing interests in a separate Audit Briefing on their information needs.

2. Those who trade with the company

Most obviously this group includes those who sell to the company who are at risk that they may not be paid if, as is commonplace, those goods or services are supplied on trade credit terms with payment being made some time after delivery.

This stakeholder group does, however, also include an entity's customers. They too can be creditors of the company, either because of deposits paid or because of guarantees offered which the company has an obligation to fulfil.

All those who trade with a company have a right to know the risk that they face from doing so.

3. Employees of the company.

Employees are almost always at risk for their unpaid wages since very few employees are paid in advance. As a result this risk is suffered by almost every employee of every company except on the day that they are paid. But employees also face other risks because of their employment. Some pay is deferred, for example. Bonuses fall into this category. And there are also pension obligations to consider, many of which are deferred over many years. All companies have a duty to account to their employees as a result.

4. Regulators

Companies are, by definition, always subject to regulation. Their very nature as legal constructs requires this, but so too does the fact that they usually exist to trade and that activity usually has associated with it many legal obligations which a wide variety of regulators might seek to enforce.

Regulators are always at risk because of the existence of limited companies. Some companies may be formed so that those setting them up can avoid those obligations to society as imposed by regulators that they might have personally if they were to trade in their own names. Those incorporating for this reason know that they will have either no or very limited personal risk arising if they use a company instead. The very essence of the company does, as a result, pose a threat to regulators.

Regulators are also at risk because when they find fault at a company the chance always exists that any penalty that they impose might be evaded by a limited company simply ceasing to trade. In this way regulators can suffer a loss which at least in part creates a risk to their overall credibility as enforcers of the law. As such regulators need to be able to identify generic risk within companies as well as the specific risks that they might be established to address.

5. Tax authorities

Tax authorities are at risk from the existence of all companies.

Some of this risk might be mitigated if the tax rates due on the profits of companies were the same as those owing by individuals undertaking similar transactions in their own names. This, however, is rarely the case, with the bias now being heavily in favour of companies. That means that many companies are specifically created to avoid tax. That gives a tax authority a very good reason to be interested in them.

In addition, the ability of companies to cease trading leaving tax liabilities owing without any possibility of recourse to the owners of the company, who may have gained from this outcome, means that limited liability companies are always a threat to the revenues of tax authorities and that is before the ability of some to manipulate limited companies to mitigate their tax liabilities e.g. by relocating profit to locations where little or no profit is payable, is taken into account.

All these factors make tax authorities stakeholders who face a high degree of risk from the activities of limited companies who have a very significant reason to be interested in the financial statements that they produce.

6. Civil society

Civil society in all its many forms may suffer a loss from the existence of a company. That company may pollute the atmosphere. It may corrupt the political environment. It could disrupt communities by its divisive activities. It may discriminate. It could promote activities that undermine communities. It may sell harmful products. And it might not disclose any of these activities when they occur, leaving a legacy that persists long after it has ceased to exist, with its owners taking their profits long before the consequences of the actions that gave rise to them were appreciated. These are very real and to the company unaccountable costs which civil society needs information on if it is to appropriately appraise them.

If accounting met the needs of these groups within society it would fulfil its social purpose. At present, we suggest it does not.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

I remember the trouble that Blair and New Labour got into over the ‘stakeholder economy’.

Looking back now, the party was slapped down by the Establishment and their bankers. It looks more and more obvious to me that there is a view that favours narrow ownership of everything by the monied few. If you are not in that wealth bracket, according to those who are, you simply don’t exist and have no rights.

It’s pure rentier thinking isn’t it? This is issue shines a light on a very dark world.

The Rentiers are in still in charge – enabled by Thatcher, and they never really went away.