I was having a discussion yesterday on the weaknesses in the financial reporting of tax by some of the UK's largest companies. The idea put to me was that these companies reported such unreliable figures for their tax owing that the only figure that could be relied upon to indicate the tax contribution that they might make is that for tax paid included in their cash flow statement.

I had to suggest to my correspondent that this situation is not new, although as far as I am aware I am one of the very few people to have actually studied it, and I last did so as long ago as 2006. In that year I published two reports on corporate tax. One was my first ever look at corporate tax gaps. The other was a review of corporate tax reporting. Both reports looked at the top 50 companies in the FTSE as it then was. Both coveted the years 2000 to 2004, inclusive. In other words, this was the pre International Financial Reporting Standard period when, if anything, UK tax reporting was better than it has been since IFRS was introduced.

One of the tests that I did in the second report was simple. I explained it like this:

Accounting is a logical subject. Certain rules can, therefore, be expected to apply to accounting disclosure. If they do not then it is reasonable to ask why that is the case. One such simple arithmetical rule is that if the opening balance of corporation tax due has the current tax charge added to it, and the amount of tax actually paid in the year is then taken off the resulting figure, then the balance remaining should be the tax due at the end of the year. This equation can be expressed like this:

Do they add up Final copy

The figure (Y) is shown in brackets since it is a deduction.

As I then noted:

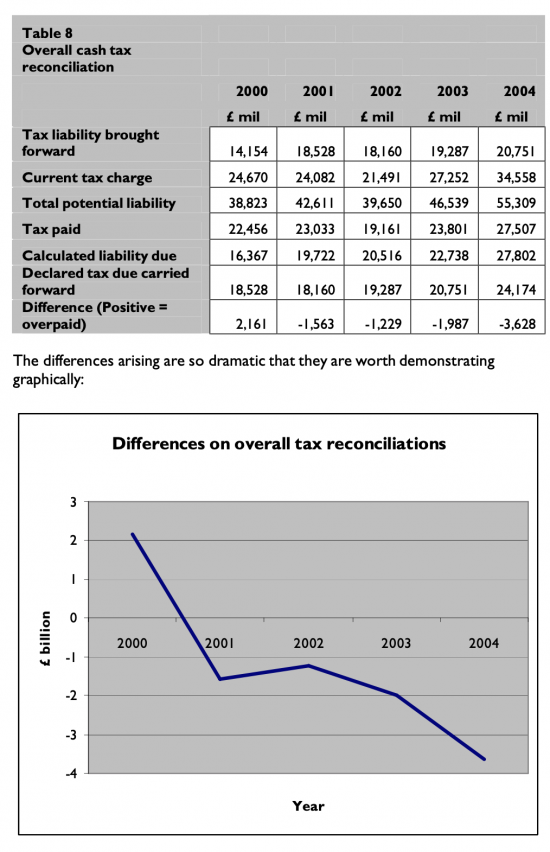

In practice the logic that has been tested does not work. Based on aggregate data the overall tax reconciliations for the period are as follows:

As I noted:

In 2000 too much tax was apparently paid. Since then in every year, and with an increasing tendency, tax has been underpaid.

It is noteworthy that the issue is not an isolated problem:

- In just five sets of accounts (2.1%) does the equation balance without seeking reconciliation from these other sources (BAA manage the feat three times, Marks & Spencer once and Associated British Foods once).

- In only 36 out of 238 sets of accounts (15%) is the difference less than £10 million.

- In 149 sets of accounts (62.6% of the sample) the difference is more than 5% of the current tax charge.

That, I thought to be material. My commentary was as follows:

It should be said that there are possible reconciling items. These include tax charges recorded in the Statement of Total Recognised Gains and Losses. Over the five year period, however, these amount to just £322 million. Net tax charges included in exceptional items have an almost equal and opposite effect. In other words, these two factors, which are the only location where tax charges should be recorded if not in the profit and loss account, cannot explain even a small part of the difference.

Another possible explanation is that the missing payments were in fact made by associated companies whose share of profits and tax are included in the accounts of these groups. But that cannot explain the positive charge in 2000, giving rise to doubt as to the validity of this explanation. Nor does it explain the fact that many companies have both positive and negative variances fluctuating (but rarely cancelling out) between years.

The other possibility is that foreign exchange re-translation may explain non payment, but the scale of the missing payments suggests that if that were the case, disclosure would be needed, firstly because the resulting gain or loss would not be tax allowable since it relates to a non tax-deductible provision, and secondly because it is material to the understanding of the tax charge in itself.

Whichever of these explanations might be true, or if there is another cause, they all contribute to an underlying concern that adjustments can be made to declared tax liabilities which are not passing through the taxation charge within the profit and loss account. This creates doubt about the accuracy of the declarations made, and uncertainty as to the amount of tax actually paid.

During this period over £6.2 billion of current tax charges included in profit and loss accounts of the UK's fifty largest companies appear not to have been paid. This is over 5% of the total tax paid and is, therefore material to an understanding of tax within these companies.

Only improved accounting disclosure can overcome this deficiency in the accounts of these companies, and this has to be a key issue all the companies covered by this survey need to address.

What is clear is that in the intervening years this problem has not gone away.

If anyone wants to look at the issue by doing some leg work on research with me (I have no funding for this) it would be fascinating to bring this up to date. Training could be given. But what is clear is that this basic test of credibility is one that accounts still fail, and that is not good enough.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Have you factored in the probability that the tax paid amount could relate to the previous year?

We know that

So we test over time…but the differences never resolve