This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. I thought it worth sharing:

Who is more powerful — states or corporations?

Milan Babic, University of Amsterdam; Eelke Heemskerk, University of Amsterdam, and Jan Fichtner, University of Amsterdam

Who holds the power in international politics? Most people would probably say it's the largest states in the global system. The current landscape of international relations seems to affirm this intuition: new Russian geopolitics, “America First” and Chinese state-led global expansion, among others, seem to put state power back in charge after decades of globalisation.

Yet multinationals like Apple and Starbucks still wield phenomenal power. They oversee huge supply chains, sell products all over the world, and help mould international politics to their interests. In some respects, multinationals have governments at their beck and call — witness their consistent success at dodging tax payments. So when it comes to international politics, are states really calling the shots?

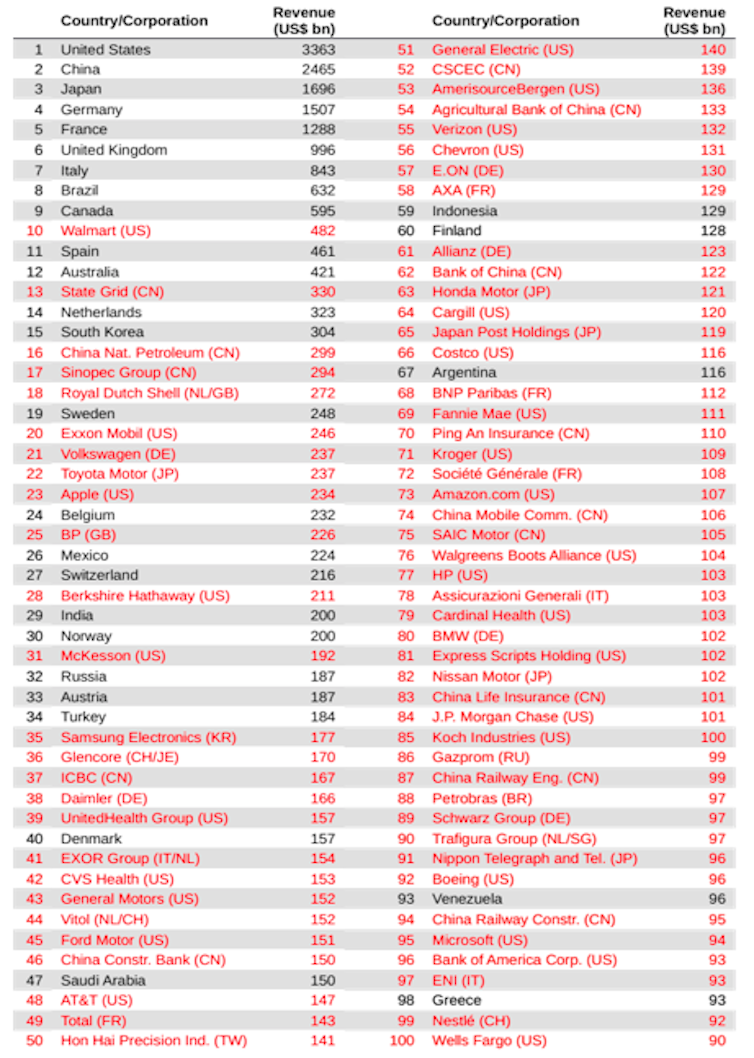

We compare states and corporations based on how deep their pockets are. The following table ranks the 100 largest corporations and countries on the basis of their revenues in 2016. Revenues in the case of states is mainly collected taxes.

States occupy the top rankings, with the US first followed by China and Japan (the eurozone ranks first with more than US$5,600 billion if we treat it as a single political entity). But plenty of corporations are on par with some of the largest economies in the world: Walmart exceeds Spain and Australia, for example. Of the top 100 revenue generators, our ranking shows 71 are corporations.

Authors' calculation based on Forbes Fortune Global 500 list 2017 and CIA World Factbook 2017.

Notice also that the top ranked corporations follow the same nationality-order as states: America's Walmart is followed by three Chinese firms. There are already 14 Chinese firms in the top 100, though the US has 27.

Our comparison is necessarily crude, but suggests that besides the very largest states, the economic power of corporations and states is essentially on par. This prompted us to try and rethink corporate power in international politics in a recent paper. We argued that globalisation has brought about a global structure in which state power is not the exclusive governing principle anymore.

Just think about the private and public power of global giants like Google or Apple. When Donald Trump recently met Apple chief executive Tim Cook to discuss how a trade war with China would affect Apple's interests, it demonstrated that the leading multinationals are political actors, not bystanders.

There always existed big and powerful global corporations — the Dutch East India Company dominated European trade in the 1600s and 1700s, for instance. But global corporations' current power position vis-Ã -vis other actors is unprecedented in terms of sheer size and volume.

How global power works

State power did not disappear with globalisation, but it transformed. It now competes with corporations for influence and political power. States use corporations and vice versa, as the following two examples illustrate: offshore finance and transnational state-owned enterprises.

To start with offshore finance, global corporations use different jurisdictions to avoid being taxed or regulated in their home country. Lost taxes due to profit shifting could be as high as US$500 billion globally. When states position themselves as tax havens, they undermine the ability of “onshore” states to tax corporations and wealthy individuals — a cornerstone of state power.

Besides tax havens, numerous EU governments have become notorious for offering “sweetheart deals” that reduce the tax burden for specific multinationals to an astonishing extent. Also, our CORPNET research group at the University of Amsterdam recently identified five countries who play an important additional role in facilitating tax avoidance: the UK, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Ireland and Singapore. Each enables multinationals to shift investments at minimum cost between tax havens and onshore states.

Turning to our second example, states have grown as global corporate owners in recent years. They now control almost one quarter of the Fortune Global 500. By investing in state-owned enterprises beyond their borders, states gain strategic leverage vis-Ã -vis other states or actors — Russia's gas pipeline holdings via Gazprom in eastern Europe are a good example. This has led some observers to diagnose a potential transformation of the liberal world order through “state capitalism”.

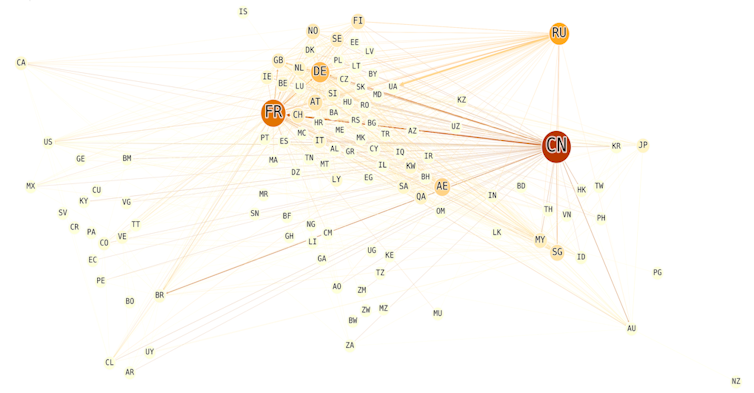

The below diagram shows the aggregated numbers of transnational state-owned enterprises or TSOEs owned by each country. The nodes represent states as owners: the bigger and darker a node, the more companies it owns outside its borders (click on the picture if you want to make it bigger).

https://www.bvdinfo.com/nl-nl/our-products/company-information/international-products/orbis

Notice the paramount position of China (CN), which controls over 1,000 TSOEs, including the likes of Sinopec and ICBC China. Countries like France (FR) and Germany (DE) are also prominent owners, but their connections to China highlight that they are targets of TSOE investment, too.

It starts to become apparent that international relations are anything but a one-sided story of either state or corporate power. Globalisation has changed the rules of the game, empowering corporations but bringing back state power through new transnational state-corporate relations. International relations has become a giant three-dimensional chess game with states and corporations as intertwined actors.

This transformation of the global environment is probably here to stay and even accelerate. Washington recently blocked the large Chinese telecommunications manufacturer ZTE from access to critical American suppliers, for example. It did this to gain advantage in trade negotiations with Beijing. The Chinese Sovereign Wealth Fund then withdrew its longstanding investment in the American Blackstone Group following Trump's push for economic sanctions on China.

![]() We live in an era where the interplay between state and corporate power shapes the reality of international relations more than ever. In combination with the current nationalist and protectionist backlash in large parts of the world, this may yet lead to a revival of global rivalries: states using corporations to achieve geopolitical goals in an increasingly hostile environment, and powerful corporations perhaps using more aggressive strategies to extract profits in response. If this is where we're heading, it could have a lasting impact on the world order.

We live in an era where the interplay between state and corporate power shapes the reality of international relations more than ever. In combination with the current nationalist and protectionist backlash in large parts of the world, this may yet lead to a revival of global rivalries: states using corporations to achieve geopolitical goals in an increasingly hostile environment, and powerful corporations perhaps using more aggressive strategies to extract profits in response. If this is where we're heading, it could have a lasting impact on the world order.

Milan Babic, Doctoral Researcher, University of Amsterdam; Eelke Heemskerk, Associate Professor Political Science, University of Amsterdam, and Jan Fichtner, Postdoctoral Researcher in Political Science, University of Amsterdam

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Sovereign currency issuing, law and war making states have more and an entirely different form of power than do corporations. This is why corporations always seek to lobby and influence governments both in their main host country and in other nations in which they operate and why they’re prepared to spend so much money, time and effort doing so.

It seems the authors of this report do not grasp the reality of money if they are using tax-revenue vs profit to compare the power of states vs corporations. A currency issuing state can outspend any corporation in the currency it issues but not only that – it can lay claim to any and all assets belonging to the corporation that exist within its area if jurisdiction and alter laws that affect corporations as per the democratic will (or despot’s will in tyrannical regimes).

Yes a large corporation backed by a powerful sovereign state will have success in bullying a small sovereign nation but this ability ultimately derives from the disparity in power between the host nation and the weaker nation targeted for exploitation.

Also it should be understood that the large corporation only became so precisely because of the backing it secured from its large and powerful host nation. If the people of that powerful nation choose to exercise their democratic power effectively they can opt to have their foreign policy and their corporations treat weaker nations fairly and compassionately. The fact we do not says more about us as people than it does about the nature of either state or corporate power.

I am hoping to work with the authors at some time

You can be sure I would raise such issues

It’s slightly trickier than that with multinationals. If states wanted to crack down on multinationals step 1 would require capital controls unless they just wanted to target the facilities located in their borders. Of course I would be all for capital controls, debt denominated in foreign currency is just neocolonialism.

Additionally I wish they used state outlays rather than ‘revenue’ because of MMT. It might even make more sense to do that for corporations, though possibly not for the banks. It’s notable how low down the banks are when it is obvious they have much more power than many of the other things ahead of them, not sure how I would adjust for that.

Banks may not have as much power as you think

Or rather, you are not looking in the right place for the banks. Almost all those multinationals have their own banks in their structures and many in fact make much of their money from finance. The fact is most of them do not now need conventional banks to do so. The shadow banking system hangs over this list.

I also was surprised to see just how far we get down the list before a recognisable bank appears.

“Banks may not have as much power as you think”, says Richard.

And then goes on to explain that ‘banking’ does not show itself in its true colours.

Contributors have already commented on (to them) glaring opportunities for inaccuracy and imprecision in the table results, but it is nonetheless an interesting list and the detail is of little consequence since many of the organisations and governments seek to obfuscate their true position.

As to the OP question: ‘Who is more powerful — states or corporations?’

I guess the answer is ‘wait and see’. Corporate interests seem to have several goals in the net in the first half. And the spectators are more interested in watching a contest at Wimbledon on their iphones. Perhaps at some stage the protagonists will agree to change ends ….. but maybe not before the spectators turn their attention back to the game and insist……?

It might have an influence on the result if the referee and linesman were to return to the field rather than be quaffing champers and nibbles in the sponsors boxes. (See previous post re Kingman review !)

This is a timely article.

“This transformation of the global environment is probably here to stay and even accelerate.”

But what is the nature of this ‘transformation. I would merely observe what seems to me a slight lacuna in the argument presented. It begins by noticing the rise of corporate power, but then turns towards a more nuanced analysis of state power expressed through corporate power. This turn is strikingly represented in the ‘nodes diagram’. Sometimes, I suspect this state direction of corporate power will typically be skilfully disguised under the term ‘soft power’. Britain began using such a vehicle over a century ago: the Anglo-Persian Oil Company. It is now called BP, and I recommend examination of its history and origins as perhaps the first major public-private venture; but primarily as a product of British ‘reason of state’.

It is much more difficult for us to disinentangle the incestuous relationship between corporate and state power than perhaps is vaguely implied in the article; perhaps especially in the West, where it does not reconcile with superficial conventional constitutional-political wisdom.

I haven’t received the daily email for a week Richard. Thought you were on holiday or something! Have you not been sending it out? Have I been purged?

I will have this checked

Richard

check for possible error – government accounts exclude double counting whereas corporations don’t.

total power is arguably not the most useful measure. the point about corporations is surely they have captured elites. Their operation through tax havens is via a very discrete but specific method (and for a long time not well known method)- the elites in tax havens, accounting firms etc. are a small group of people.

Comment on ZTE is incorrect. ZTE is a genuine national security issue and had arisen long before Trump’s entry into government and commencement of his trade policy. His dropping of the sanctions on ZTE was as part of trade negotiations but Congress imposed a legislative block.

Richard, I have also stopped receiving your daily posts.

Regards, John

I have been looking into the Vietnam War recently. I think corporate influence is all over that war – pre-dating globalisation – the so-called military-industrial complex that Eisenhower identified.

Private American corporations certainly saw US presence in South Vietnam as a means of selling more products in the South. When the Vietnam war ended, the South’s economy collapsed as the West pulled out – such was how deeply American business become part of South-Vietnamese life.

But also public corporations too managed by the Government are involved – the US Army for example could be seen as public corporation of sorts and was always asking for more troops, more weapons to prosecute even though the politicians knew that they could never win the war (the so-called military

American tobacco companies seem to have a presence wherever the US is operating overtly or covertly around the world. Look at South America.

And look what happened in Iraq. Halliburton and Co.

So state sponsoring and legitimisation of public and private corporations is part of the problem. We must not lose focus on how many of today’s politicians might have started their careers in business and are actually there to pursue their previous interests but now within the apparatus of democracy. This remains one of the biggest problems with modern democracy for me. By all means look at the corporations but also look at where they find favour with the State.

For me, I would much rather the State be more powerful. You can vote the State out if it is not doing its job. The State can also have more broader accountability thrust upon it than corporations – whose investors must, by law, come first and whom are the only real people corporations seem to be responsible to. The laws that underpin such thinking totally undermine and render useless any idea of ‘corporate responsibility’ and must be repealed as part of any rebuilding of society.

PS – Sorry about the poorly written contribution above but I hope that it still makes sense.

It does