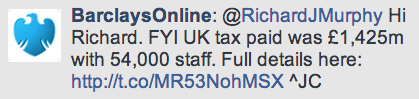

I wrote yesterday about Barclays' country-by-country report and what could be gleaned from it. The Guardian referred to that work in this morning's paper. Barclays did not like what I had to say, tweeting:

That's just nonsense, for reasons I had already explained in my blog on the issue.

Others have asked that the fuss is all about and who cares that Barclays is not paying tax in the UK as their overall tax rate is 28.9%, which is more than the UK rate, to which my answer is that it is good that the USA, Germany, South Africa and India may get the tax they think to be owing, but I would like the UK to do so as well, but it is very clear that tax havens are preventing us doing that.

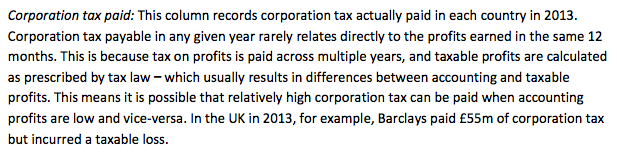

However, such commentary also makes clear why there are problems with this data and such a limited form of country-by-country reporting. The biggest weakness by far in this data is an issue on which I warned the EU when they proposed this formal disclosure, and of which I warmed the UK government when they planned the detailed requirements for publication. This is that whilst current-year profits are required to be disclosed, the figure for corporation tax is that actually settled in cash during the course of the year, and there is little accounting relationship between the two. As Barclays themselves say:

This confusion could, of course, have been readily resolved by Barclays. They did on this occasion voluntarily publish information from their accounts for most of the countries in which they operate. They could, very easily and at no cost to themselves, have published information from those same accounts on the current-year tax liability that they thought might arise as a consequence of those profits being recorded. They chose not to do so. Instead they have published what they admit to be misleading, and mismatched, information on the amount of tax paid during the course of the year.

Now, I know that this is what the EU requested, but that was because they remain in the mindset of the extractive industries, where payment information has proved to be vital, whereas with regard to other multinational corporations the comparison between declared liability and tax paid is at least as significant. But, rather than address this issue, which they could have done, Barclays has, I stress voluntarily, published information which they know does not give a fair representation of their tax liability during 2013 even though that is what the document that they have produced claims to provide.

As a consequence, the first thing that we have learned is that if companies wish to avoid confusion arising then they need to voluntarily publish information on their tax liabilities arising during the year for which profits declared. I stress in this regard that when I refer to tax liabilities, I mean their current tax liabilities because that is what they expect to actually pay, and not to their deferred tax liabilities, which might never be paid.

Secondly, whilst Barclays have usefully, and appropriately, reconciled the information that they have published to the group accounts, showing the main variations that have arisen, their failure to allocate these reconciling items to jurisdictions has given rise to a seriously misleading representation of where their profits might arise. That they have done this does not help their case. For example, part of the profits arising in Luxembourg may, in fact, represents dividends received from other countries on which no tax was due. If that was the case, then it would have been to Barclays benefit to declare the fact. Similarly, they imply that part of the profit arising in Jersey do ultimately arise in, and are taxed, in the UK, but again if that is what they wish to communicate then they must show how that situation arises with sufficient information for an informed user to see how this claim is substantiated. I would hope that companies quickly realise that partial country-by-country information does not help their case, but full disclosure might.

Thirdly, it is interesting the Barclays voluntarily disclosed information with regard to taxes paid which, as they admit, have no relationship to profit, even though country-by-country reporting has always had its focus upon taxes due on profit, and nothing else. As I've already explained, this information is curious, but adds nothing to understanding. Barclays cannot claim that there is something special, or unique, about it paying employers National Insurance with regard to its staff when those people could just as readily work for another employer, who might make the same contribution. It is the taxes the Barclays actually pays itself (and just about all economists do, for example, agree that employers National Insurance is a cost borne by employees) that really matter.

Fourthly, the 'other' category within this data could hide a multitude of sins. We do, for example, know that Barclays has a significant number of Cayman Island subsidiaries and yet there is no reference to the Cayman Islands in its report, which has to make it misrepresentation of what is really going on within the group, and how it structures itself. Thankfully the OECD has realised that country-by-country reporting only makes sense when each and every jurisdiction has data disclosed for it, and is moving in that direction with regard to the requirement for tax disclosure that it will be demanding later this year. Barclays has not yet had the good sense to realise this, and as a consequence leaves a whole host of questions open as a result of only partial disclosure being made. Suggesting that it so happens that more taxes are paid in these other jurisdictions than might be due at the UK rate is insufficient explanation for what is happening.

The reality is that what we got from Barclays is extraordinarily useful. If wholly justifies the demand for country-by-country reporting because we do know now for the very first time just how dependent this group is upon transactions routed through tax havens to generate profits and for tax reduction purposes, even if it's overall apparent rate of tax remains higher than the UK rate as a consequence. But what the data also suggests is that if companies are wise they will anticipate the reasonable questions that the information that they supply is likely to give rise to and will, as a consequence, supply information of the types that I've indicated, because that will save them from a great deal of aggravation in the future because the data that they publish will otherwise be knowingly misleading whether it complies with legal requirements, or not.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here: