Since 2009, HSBC and Barclays bank may well have underpaid UK corporation tax to the tune of £2.6 billion. This figure represents the difference between the tax the banks actually paid and what would have been due had they been taxed under what's called a unitary taxation system. The data's in a new report I have written with Meesha Nehru for the Tax Justice Network. As we argue, year on year, this is an extra £650 million that just two banks could be contributing to the Exchequer if we had a fairer corporate tax system in the UK. To put this amount into perspective, according to HMRC the total contribution of the banking sector in corporation tax (on income as opposed to the separate bank levy on debt) in 2011-12 was £1.3 billion.

Under the current policies of economic austerity when vital public services are being cut, and the vulnerable are being made to suffer, there is more need than ever to ensure that those responsible for the current crisis, including all our major banks, make a fair contribution to the public coffers. However, under current UK and international tax rules, HMRC can only tax HSBC and Barclays based on the profits the companies declare that they make in the UK.

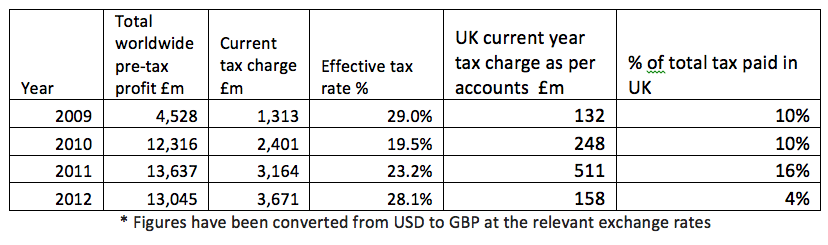

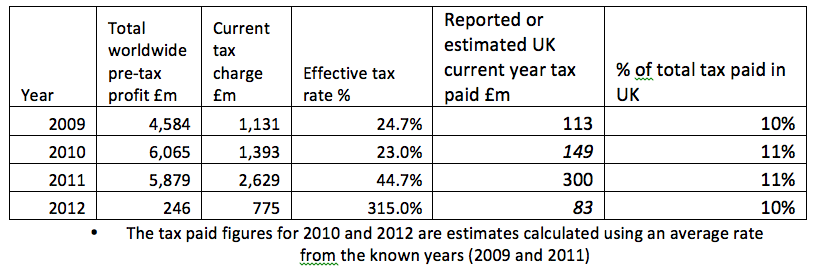

The two banks currently suggest that they pay roughly 10% of their total tax bill in this country:

Table 1 HSBC Holdings plc*

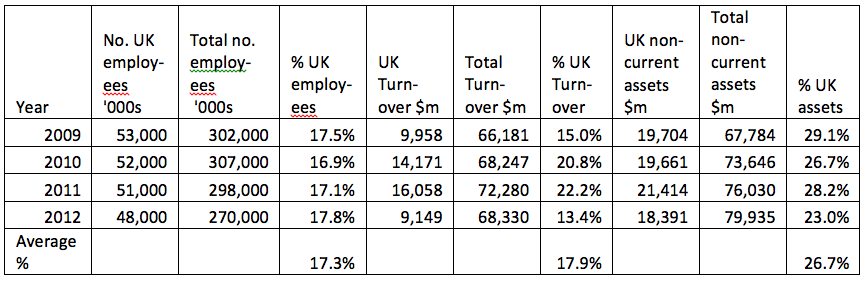

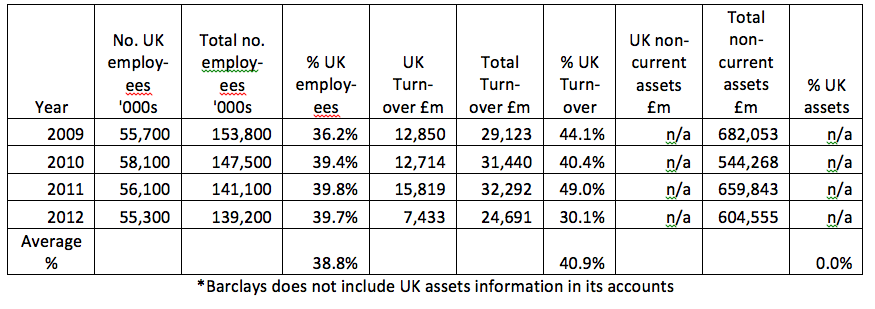

If these ratios of tax paid were a fair proportion for each bank then that would suggest that they both generate the vast majority of their profits and conduct most of their economic activity overseas. That, however, is not true. Both British banks are headquartered in London and have a substantial presence around the country. This is reported by both in their accounts. HSBC reports its UK presence as follows:

Table 3 HSBC Holdings plc

Table 4 Barclays plc*

What is obvious is that the proportion of tax paid in the UK does not in any way match the level of activity that these banks seem to be undertaking in this country. This is all too easy for a bank to arrange. Non commercial organisations have better access to tax havens and none find it easier to shift where they earn their money by the simple process of moving money between accounts as a result of just a few key strokes on a computer.

That is why the Tax Justice Network has explored the level of tax that might be paid if a more appropriate international taxation system were to be adopted, as could be the case at the G8 summit that is looking at this issue in June 2013.

The best alternative to the current international tax system is unitary taxation. Unitary taxation has been around since the 1930s and is used in the USA to divide income between states. It works by using a formula to divide up the total profit of a multinational corporation and its group proportionately between all the countries in which it operates.

The most common formula used allocates the profit of a multinational corporation to states according to the amount of turnover, the number of employees and the percentage of real, tangible assets such as buildings and machinery that the firm has in each jurisdiction.

The logic behind the formula is that companies cannot make profit without having customers, people to service them and places where they can work. Using it also better reflects the nature of multinational corporations, which are run as if they are one giant enterprise with a single board of directors and not as a whole host of wholly unrelated companies, which existing tax rules assume.

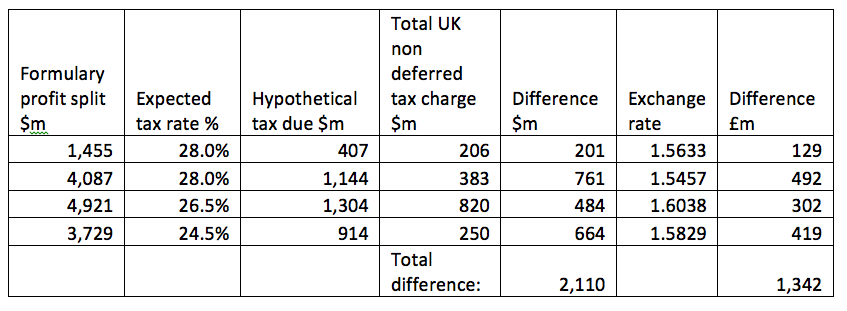

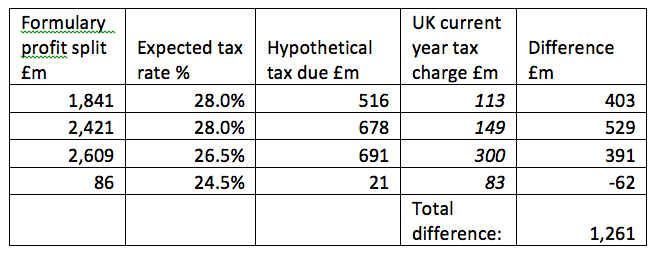

Applying the formula to these two banks suggests that over four years HSBC paid less than half of what it might have owed if profits had been allocated in this way, whilst Barclays only paid around a third (note: asset data is not available for Barclays so just sales and staff were used):

Table 5 HSBC Holdings plc

Table 6 Barclays plc

A broken system

The likely reason for the gap between the tax these two banks actually pay and what they would owe under a unitary system is profit shifting. Profit shifting is the name used to describe the behaviour of multinational corporations when they use complex structures to move profits they have earned from one country to another.

They do this with the aim of increasing the profits that are declared in low tax jurisdictions whilst reducing those declared in relatively higher tax jurisdictions, such as the UK, with the aim of saving tax. This lay behind the recent revelations about Google, Amazon and Starbucks tax affairs.

Profit shifting by multinational corporations is now recognised to be a massive international problem. David Cameron has made it the focus of the G8 summit in June and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, which sets the rules for international taxation, acknowledged in February 2013 that the current system is broken.

Both HSBC and Barclays have a history of tax avoidance: HSBC stands accused of helping customers evade tax and launder money in Cayman and elsewhere whilst Barclays' former Structured Capital Markets Division was notorious for selling tax avoidance schemes. A 2011 survey also showed that the banks hold between them around 940 subsidiaries in tax havens, many of which might exist solely to facilitate the process.

Banks not paying tax is a known problem. Failure to address this issue is increasing the severity of the austerity programme being imposed on the people of the UK. The Tax Justice Network believes that unitary taxation is eventually the only logical way to overcome the problem of profit shifting that is at present letting multinational corporations walk round taxation law.

Our Prime Minister seems to agree. In Davos in February 2013 he said:

When some businesses aren't seen to pay their taxes, that is corrosive to the public trust.

We have to trust that our banks, to whom so much has been given, justify the faith we have placed in them by paying their fair share in taxes.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

“When some businesses aren’t seen to pay their taxes, that is corrosive to the public trust”

The thought bubble accompanying this statement was probably more along the lines of:=

“Damn, if only this issue hadn’t been highlighted to the general public by those pesky NGOs and Charities, we wouldn’t give two hoots! Now how can continue to make the UK business friendly*, while appearing to do something** about tax avoidance.”

*ie allow our friends to continue ripping off the State.

**ie nothing

David Cameron making a lot a noise about tax avoidance has more in common with Richard Pryor’s acting in the “We Bad Scene” from “Stir Crazy”

http://www.metacafe.com/watch/357049/richard_pryor_gene_wilder_we_bad_scene_from_stir_crazy/

Not a single mention of the cost of capital? If I was any company with two division, one a UK division, the other an emerging market division, then the cost of capital would be significantly higher in the emerging markets division to reflect the far higher risk of doing business there. This would mean that I would need to have higher profits in the emerging markets division to meet that additional risk. So even if my company had equal employees, assets and turnover, I would expect to generate far higher profits in the emerging market division than the UK. So a unitary tax approach would not be taxing the business correctly at all. In fact, I would think it unlikely that there are many businesses that earn similar profits margins to sales, employees or assets across countries, given they often operate in substantially different industries. Even a company that has identical processes anywhere in the world – brewing being the perfect example – earns wildly different profit margins across countries and unitary taxation would bear no relation to the economic reality. I can see how country by country reporting can be a massively powerful tool to combat tax evasion/avoidance, but can’t see how unitary taxation could actually be implemented.

It’s a group

Let’s get real: that’s one of the synergies of being a group

Tom makes a perfectly valid point. Unitary taxation isn’t a panacea, there would be cases where profits went to the wrong place.

Not all employees are equal when it comes to profit creation, not all buildings are as important to profit creation and turnover in different countries results in different levels of profit.

If unitary taxation comes in corporations would move what they could, which would largely be low skilled jobs that could be done anywhere, along with physical assets. It might even encourage more tax competition between countries. Base your staff in a country, bring jobs and they will reduce your global tax bill under unitary taxation.

Which is why we do not argue for fixed formulas

Tax authorities will need to agree them preferably bilaterally but if not, as now, unilaterally

dont the banks have a lot of tax losses carried forward (certainly in the UK) which will clearly distort the amount of tax paid. Does a unitary system accomodate the concept of tax losses?

Yes, if they’re real, of course it does

It is based on real profits

So the carrying forward of UK tax losses from 2007/8 might have had some effect on these numbers then?

Have you not noticed they are paying tax?

We’re only dealing with that reality here

Tell me how you’re suggesting I have changed that?

And do you really think all losses were in the UK? Are you that blinkered?

ok, so in the analysis how are the brought forward losses factored in – i have read the TJN report you linked to and it dosent even mention them (which seems a bit odd as its not exactly a secret how much money they lost !)

These companies are paying tax….

You seem to be ignoring that

Im really confused – has anyone actually read the tax notes in the Barclays 2012 accounts? they have over 8bn of losses, and they have a huge gain (which is non-taxable due to SSE presumably) which is flexing their tax rate, amongst other things

please dont tell me the TJN analysis has overlooked SSE again (remember the analysis of the Guardians ETR a few years ago)

We did the analysis over several years

We recognised their very high current tax rates in some years

And we recognised the realities of their business. There was no need to take the note into account – our work had already done so

You overlook the fact that in recent years UK bank profits have been destroyed by provisions made for misselling and other fines. Most of these are purely UK based costs and hit the UK P&L entirely.

If it wasn’t for their overseas operations, it’s unlikely either Barclays or HSBC would have made any profits at all.

Hang on – are fines tax deductible?

No, as far as I’m aware CIR v Alexander von Glehn Ltd [1920] 12TC232 still stands!

http://www.hmrc.gov.uk/manuals/bimmanual/bim42515.htm

It would be egregious if the banks received a further subsidy from the taxpayer!

Some fines are and some aren’t, it depends on who levies the fine (remember the Formula 1 story), but certainly a government fine isn’t going to be I would think. However the cost of compensative customers probably is tax deductible I would have thought?