Tim Worstall, who likes to think of himself as my bete noire, but who is actually a rather pedantic former UKIP press secretary (which explains why most of the world treat him with all the respect due to such a person) has published what he calls a report for the Institute of Economic Affairs, the right wing fundamentalist think tank, on the subject of financial transaction taxes, or Robin Hood Taxes, if you prefer.

Well, I am kind to it to call it a report. Spread over 14 pages, six are blank or are titles, contents pages and introductions that add nothing of substance. Of the remaining pages most have less than half a page of text on them. Whilst I agree that volume does not equate to quality, in this case it does: the report is so flimsy as to evidence it is laughable.

So what does it say? First of all it agrees that an FTT is feasible. Some of us have always known that. At least that's been conceded now by Worstall. Better still, at least he only took half a page to concede the point. But that's where the good news ends.

Second, Worstall argues that the tax will not raise revenue. This argument is wholly premised on the claim he makes that the proposed EU charge will be levied at 0.1%. In the process he ignores the fact that, as Reuters notes:

Under the [EU] plan, stock and bond trades would be taxed at the rate of 0.1 percent, with derivatives at 0.01 percent.

Worstall never mentions the lower rate in his report. He entirely ignores the fact that most of the tax will be charged at a rate one tenth of that he uses for the purposes of his analysis. This is like considering the impact of having an income tax at a rate of 20% and using a rate of 200% for the purposes of the analysis. Unsurprisingly you would get a result from such an analysis somewhat bigger than most other commentators would predict. To put it another way, you'd just be wrong, as Worstall so very obviously is in this report by making such an elementary error.

Third Worstall assume that marginal rates of tax in Europe are between 40% and 50%. That's not true. Average overall rates in Europe are less than 40% based on research I will publish very soon and since most tax systems are regressive at the higher end where the impact of this tax is likely to be rates should be lower than he forecasts. That's lazy on his part.

As is his claim that the tax could not happen because it is illegal in the EU. Well of course it is: there is no law that permits it right now so the law will have to be changed if we want a financial transaction tax. That's that objection overcome.

As indeed is the further objection that the tax must be undesirable because it would be paid to the EU. There are three reasons for objecting to this argument. First, the EU has to be funded. Why may it not tax? Secondly, if governments permit this then what is his problem with that? The governance and accountability structures for such a decision are clear. Finally, on this issue, Worstall seems to assume that tax paid is always wasted. It's an interesting idea, but of course wrong. Indeed, if his own argument that corporations can't ever pay tax is right (with which I do not agree, for reasons noted, below) but about which he is adamant then by simply using the same incidence argument the entire benefit of this tax when collected cannot be for the benefit of any government as he argues but is instead passed on to people — an argument people like Worstall always ignore when discussing incidence. He gives no consideration to the benefit that they might derive as a result, or the dynamic consequence of it, for example on new investment, spending, resources for regions, the reduction of burden on indebted governments so they can provide essential services, and so on. It's just all a cost according to Worstall, meaning his analysis is totally distorted. But he can't make such a one-sided argument. If redistribution increases resources available to those who really need them in society, especially at a time when those with wealth are saving and so increasing the impact of the recession through the paradox of thrift, then his argument fails miserably. I contend it does.

As incidentally do his own arguments on incidence. He can't both argue that corporations if charged to this tax will relocate transactions to avoid it and at the same time say that the incidence is never on corporations, as he does. Firstly, if the incidence is never on corporations they would take no action to avoid the tax. In his world of rational beings he can't suggest corporations are both logical and yet would behave so irrationally to avoid a tax they will not pay. So the truth is vastly more complicated than he suggests and the mainly very old papers (1970s and 1980s) that he quotes in favour of his argument may have been selected for exactly the same reason. First, companies are not just bundles of contracts that mean they act merely as agents for human beings. This is what Worstall implies and it's a claim about as close to reality as is belief in the Efficient Market Hypothesis — and as surely now reserved for the same sort of fantasists who think markets work as their economics textbooks describe, and who quote each other's text books as supposed evidence that this is indeed the case rather than look to the real world they'd rather not embrace for evidence of what really happens.

I've addressed this issue many times before, and the extraordinary and I think near fraudulent evidence some supposed economists put forward to argue that it is always labour that pays the price of any tax but let me summarise my reasoning again. First, in addition to the obvious belief of management that the incidence of tax clearly is on their companies, there is much other behavioural evidence on this issue. Companies can, for example, very clearly choose in a great many cases when, where, in what form and to some degree in what amount they record transactions and so tax. They very clearly therefore decide who might bear that tax, where and when if that incidence is not on the company itself. That is enough to think this not a neutral issue.

Second, as I have argued, there is good reason to think in the case of financial transaction taxes that this incidence may indeed fall on labour — but not generic labour as Worstall argues, but the very particular labour of bankers who will suffer a loss of bonuses and maybe employment as a result. Given that the activities of a great many of these bankers has properly been described as ‘anti-social' by Lord Turner there is considerable reason for thinking that a thoroughly desirable outcome with enormous gains for society itself. By ignoring this possibility Worstall shows that he thinks the only reason to tax is to raise revenue when that is just one of five reasons that I and others recognise, including the objectives of redistribution and repricing antisocial activity, which this tax undoubtedly does.

Third, if banks were split, as I and many others suggest, the chance that dealing on own account (which explains a substantial part of the transactions that will give rise to a financial transaction tax being paid) will not be capable of being passed on to ordinary customers in the way Worstall manages, constraining these transactions within investment banks in the main and therefore meaning most of the incidence will remain within the quite limited sphere of activity that these banks will influence, including their shareholders.

Next, to assume that the liquidity that financial markets often suggest exists is a good thing is a wholly mistaken assumption on Worstall's part. If there was less liquidity in these markets there would, very obviously, be much less volatility than we are witnessing at present, and much less chance that these markets could be used to mount the assaults on democracy that their Goldman Sachs' derived leadership currently seems to be undertaking. As important, this liquidity is illusory: when the markets really needed liquidity in 2008 it famously dried up, almost completely. The idea that liquidity is always by default good is simply not proven to be true.

Last, for now, given that what is clearly needed with regard to most capital investment is very clearly a long term view, and not the short term mania that currently passes for supposed investment management, there is actually very clear evidence that imposing a tax on short termism will increase the quality of decision making and reduce the burden of investment churning that is currently passed on to markets as a result of excessive, exploitative and deliberate abuse of the like of pension funds, where the members have no say in how their savings are abused in this way. The cost of capital may or may not increase as a result but the quality of return to investors will undoubtedly rise as a consequence, and that is what matters.

And this too is a characteristic of the failure of another Worstall's assumptions — which is that any fall in GDP must be a bad thing. I do suspect and even hope that an FTT will reduce GDP in the short term. I have every wish that the not just useless but also harmful activities of many involved in anti-social gambling at public expense be eliminated. Reducing GDP for this reason would be as welcome as a fall in GDP resulting from the ending of pollution or the ending of divorce — both of which add to misery and GDP at the same time. GDP is not a god to be worshipped for its own sake. But in this case there's more to it than that. As I argue in the Courageous State (chapter 12, for those with a copy, and this may be from a draft and not quite as finally published, but there will be little in it):

It's my suggestion that the UK has considerably too much banking and financial services activity for its own good. It's my belief that it represents an excessive proportion of economic activity. More than that: I believe that this excess actually squeezes out other more productive economic activity that would be of benefit to the UK.

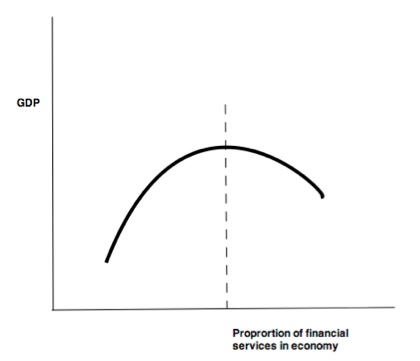

Let me put this idea on a graph:

As the proportion of financial services in an economy rises then I am clearly suggesting that benefits can arise: money is an amazing thing with the power to release all sorts of advantages and it would be wrong to deny it.

But I am also suggesting that there comes a point over the longer term (and all that I am saying here is an analysis over time because the impacts being discussed arise over years and even decades, not days and months) when those advantages can be outweighed by an excess of financial services in an economy. Too much banking can crowd out real money making in real business that makes goods and services people want and need. This is the widely recognised economic concept of ‘squeezing out' in operation.

The same can also be true of too much speculation within an economy as opposed to real wealth creation. It would appear glaringly obvious that having large numbers of intelligent people spending their lives gambling cannot be good for the generation of real well-being and yet this is encouraged in our current economy. Since speculative trading is not the same as making things the diversion of real talent towards the moving of money around the financial system can eventually deny talent to the production of goods and services, education and art, care and creativity that any society really wants and needs.

When this happens — when squeezing out occurs - I suggest that the long term GDP of a country actually goes down because there's too much banking going on. And that's what this graph shows: there is a tipping point beyond which too much speculative banking is not good for us. It's my suggestion that we reached that point some time ago and that we are on the right hand side of this graph now, where the return from banking is a reduction in our national income.

In other words: am apparent fall in GDP from banking right now will increase GDP overall because banking is very clearly squeezing out ore productive activity in our economy that cannot happen whilst mispriced activity takes place in banks because as, for example the Mirrlees Commission even agrees, they're under-taxed when it comes to transactions (which is, I note something Worstall ignores). This logic is similar to that of the supposed ‘squeezing out' of the private sector by the state so beloved by the right wing, even if without apparent evidential support in that case whereas in this case the support for the claim that key resources (and most especially mathematically literate graduates) are denied to productive industry as a result of the destructive impact of banking is overwhelming.

So has Worstall made a case that FTT's fail? No, not at all! Far from it in fact. What he has done is instead assembled a polemic, based on a mistaken assumption of the tax rate to be used and then, relying on just one quote from the EU has said, by applying inappropriate tax rates for the EU zone and assumptions on corporate behaviour for which there is no evidential support in the real world coupled with myths that because there is no law allowing an FTT at present they must be illegal, claimed that they therefore cannot work. And very amusingly he has then claimed that his resulting logic is unassailable.

With the very greatest of respect to Tim, that's just not true at all. As I have shown, the whole edifice on which he mounts his argument is flawed, his choice of evidence is flawed, his data is wrong and the resulting claim is just a piece of wishful thinking no doubt designed to keep those who fund him and the Institute of Economic Affairs very happy. But that's not the same as making an irrefutable case. That he has utterly failed to do — not least because of Worstall's own refusal to consistently apply his own logic, which means, as I show here, that his resulting logic is so partial it is obviously wrong.

Financial Transaction Taxes are according to Tim Worstall feasible. On that we agree. But most importantly, they'll also work. On that we don't agree, but only one of us is right. And I'm very confident that a proponent of the economics that has brought the world's markets to their knees is not the one on this occasion who comes even vaguely close to the truth. Bad luck Tim, therefore. It's 2 out of ten for effort, but no points at all for getting near the right answer.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Let battle commence!

The ‘incidence’ argument, like the You’reHavingALaffer Curve, is an example of a trivial truism twisted and blown up into a massive ideological shield by the loony right. Taken to its logical conclusion, we should only levy taxes on poor people like me, as us ragged-trousered philanthropists are the only people unable to pass it on.

The transaction tax is feasible, but lets look at the proposed at the proposed destination of this tax. The tax is all collected by the EU bureaucrats in Brussels. The UK contributes far too much to the EU already, a deficit to the UK of £45,000,000 sterling a day. Why contribute more? Change the destination of the tax to help the UK reduce the deficit.

Why?

Th UK has not even agreed to such a tax

If the EU does why should the UK get it?

I didn’t say it was desirable, I certainly don’t think the EU should levy it, that the EU take a share of all VAT takings is enough. If there was such a tax the UK should collect the gains of income earned in the UK and use it for the National good.

Barry

it would be difficult to decide the provenance of each transaction & possibly not cost effective to bother.

To me, it seems odd that I get taxed punitively for drinking & smoking myself to death, things which only affect me, yet speculators that cause massive swings & dips of bonds that result in the poor people of Greece, say, being unable to survive, pay not a penny on their dispicable & iniquitous speculations.

The UK is one of the largest members of the EU both in terms of population and of wealth. Using the redistributive principle, progressive taxation, it’s not surprising that the UK should be a net contributor to the EU budget. That budget doesn’t just pay for bureaucrats but actual redistributive purposes, trying to bring the poorer parts of the EU like Greece and Portugal up to a better standard of living, through development of infrastructure. This is the same as redistribution within a country, the poorer and less developed parts of the UK generally receiving more spending than they generate in tax revenues.

I make your figure about £16bn annually which appears to be the total contribution from sugar levies and customs duties (the EU gets 75% of these), a percentage of VAT (0.3% of national VAT revenue, corrected with a weighting factor for different VAT rates, this ‘VAT base’ limited to 50% of Gross National Income), and a percentage of Gross National Income (0.7538% for 2011). You don’t seem to have allowed for the UK’s rebate of €3bn (based on 66% of the difference between the UK’s contribution in VAT and what it receives back in spending, with adjustments due to the shift to payments based on GNI and changes in rates), nor the actual amount of spending from the EU budget.

This transaction tax wouldn’t be greatly different in character from the sugar levies and customs duties, which are framed as EU taxes that the Member State is allowed to retain 25% of (up from 10% in 2001).

I disagree that derivatives should attract a lower rate. Derivatives are fundamentally for gambling, not for investment, and should attract a higher rate. Particularly we must distinguish financial derivatives – options on shares – from commodity futures, where speculation is actively harmful and is still driving crude oil prices (in particular, but commodity prices in general) far above true supply and demand of the underlying commodity.

@Mike

While derivatives can be used for speculation, they are very important for real businesses esp commodity users. Farmers sell corn futures, meat companies buy corn futures, gold miners sell gold futures, jewellers buy gold futures, oil companies sell oil futures, airlines buy oil futures. The speculators sit in the middle, providing liquidity to the real participants. Their ability to impact the commoditiy markets is insignificant compared to nations that stockpile commodities and manipulate markets.Surely a better way to reduce specualtors is by better regualtion of naked speculation rather than a shotgun approach, but then again it is much nicer politcially to raise a new tax.

It also works….

And as there’s tax on insurance why not on speculation for the same purpose?

Seems fair to me…..

Isn’t the percentage rate of the FTT tax the wrong way round? Personally, due to the economic dangers derivatives pose, I would tax derivatives at 0.1% and bonds at 0.01.%

Of course, there might be an argument for taxing them both at 0.1. However, I’m sure I read that the agreed figure on this tax was 0.05%?

Of course, Cameron wants this tax stopped as around 75% of EU finance goes through the City of London. And of course, we can’t do anything that might conceivably affect the vast profits of the City, can we? After all, he has to do the bidding of his paymasters.

0.05 is Robin Hood Tax

i quoted EU proposals

Worstall didn’t even read their report by the look of it

You are wrong on liquidity, higher liquidity reduces volatility, it is the lack of liquidity that is responsible for the volatility that we see currently.

Also you seem to argue the case from two conflicting sides, on one side it will give much needed tax revenue but on the other side it will stop anti-social banking, reduce illusioaruy GDP and not impact real business transactions. Unfortunately you can’t have both sides!

The EU rates are set to raise revenue – they’ll do that

I want higher rates to reduce activity – that would work too of rate higher

I can have it both ways – they’re separate arguments

And it’s you who is trying both ways on liquidity

FTT: or how the UK/EU should shoot itself in the foot. Unless it were agreed universally (worldwide). Then it would be a worldwide self-foot-shooting party.

Thankfully no-one would be stupid enough to let it happen. Surely!?

The only fools are the 1% who oppose it to preserve them against the 99%

We often hear of the annoyance expressed by the US. They are trying to promote peace in Afghanistan but are completely undermined by organisations in Pakistan which they cannot control.

For various reasons, we hear less about the annoyance expressed by the EU. They are trying to promote stability in their own region but are completely undermined by organisations in the City of London which they cannot control.

Rather decently, they aren’t proposing drone strikes (yet). They just want an FTT that will discourage behaviour that almost everyone agrees is massively damaging to the world economy. What’s to disagree with?

It is an empirical fact (as well as a logical deduction from either classical or “modern” theory of investment) that reducing liquidity increases volatility. That is not my reason foe opposing the ridiculous tax proposed by Barroso – I just think that you should know that.

Tobin’s original proposal was not planned to raise money but to reduce speculation in the Forex market: as such it had some merit, but the EU’s lawyers say that a tax on Forex would be illegal. Barroso’s proposal is either stupid or a negotiating ploy to put pressure on David Cameron. Last month there were about 0.44m transactions on AIM: for a majority of companies, accounting for a majority of those bargains,the average bargain size was less than £5k, so the cost of accounting for the tax would exceed the tax paid. That is an obvious wasre of money and just plain stupid.

The tax collection would be wholly automated

Modern investment theory is just that – theory

it is unrelated to reality, assumes markets and players that do not exist and knowledge tha is unavailable and therefore should be ignored. It got us to the mess we’re in

Ands yes I am a Tobinite on this tax

But I won’t say no to the revenue

And as to saying it will cost more to collect than worth – odd how you can use quill pen arguments when it suits you

What is very clear is that you have no objectivity at all

Firstly, empirical facts remain facts even when discredited theories happen to coincide with them. Secondly, I said “the cost of accounting for the tax would exceed the tax paid” not the cost of collecting it. Thirdly, the stockbroker is required to account for the cost of the transaction in detail to its client on every transaction and the going rate for the cheapest online dealing has settled down around £7 per bargain. As well as sending a monthly or daily payment to Brussels the broker would need to round the tax on every single transaction to the nearest (or higher, or lower depending on the wording of the regulations) penny and account for it three times.

Fourthly, how can pointing out objective facts demonstrate a lack of objectivity?

You really do push the boundaries of credibility

Every single aspect of this will be wholly automated and you know it

As I said, stop playing the quill pen argument and you might be a little more credible

As it is quite candidly you’re just showing you’re clutching desperately at straws to justify abuse

Can you please explain why less liquidity would very obviously lead to much less volatility. It’s not obvious to me.

As Keynes argued, lower liquidity can result in fewer transactions

They tend to be more reflective with considerably less chance of short term speculation

So less volatility as fundamentals are valued more

It’s al fairly obvious, I’d say

It’s obvious that less liquidity would result in fewer transactions. But much less obvious that that would reduce volatility. What measure of volatility are you talking about?

Paul B Just to add to what Richard says. If you add additional costs to trading, the volume of trades will reduce and those trading will take a longer term view of their positions. I agree completely with Richard that our Financial Services Sector is completely overblown. Much of the trading is pure speculation/gambling that provides absolutely no benefit to the true economy. When you examine the true bank bailout/subsidy figures provided to the Financial Services sector compared to the net tax paid, the sector actually contributes less than 2% of GDP. The risks of having so much of our economic stability resting on this sector is far too high a price to pay for keeping these speculators in the obscene financial condition they now are lobbying so hard to keep.

I think Adair Turner got it right

He called our financial services industry ‘anti-social’

And an FTT is a price to pay to bring it back into order, I suggest

I’ve always been sceptical of the Tobin Tax, knowing that Tobin himself turned against the idea. I agree with Richard that the object should clearly be to ‘throw sand into the works’ not to raise revenue. I think the odds are stacked against it ever being implemented. I think that there may be unintended consequences if it were. However, I fully support the idea of giving it a go, because it might indeed succeed in its objectives and it’s fun to watch the finance sector getting ‘frit’.