A lot of organisations — unions, NGOs, journalists, others — have asked me questions about the tax gap of late and who seems not to be paying their fair share.

I mused on this, looked at the data I have and come up with a surprising example. It’s Marks & Spencer plc.

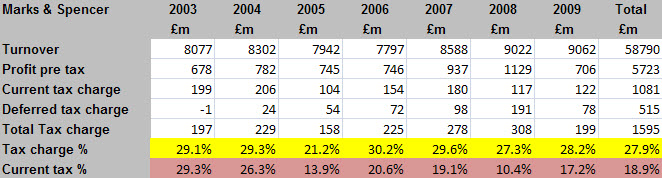

Here’s the relevant data:

For those who want more, it’s in a PDF, here.

The yellow line shows the headline tax rate for M&S — which is really rather comfortable. For 2003 to 2008 the headline tax rate in the UK was 30% and then in 2009 it was 28%. M&S hovers around that figure — and all very good it looks.

But underneath that comfortable marketing line from the profit and loss account is the much, much lower current tax line — and that’s the figure the company actually expects to pay. This is low: lower than that for Tesco, Sainsbury's and Morrisons, with whom it might be fairly compared in the FTSE 100, and even that for Barclays Bank — who some consider a tax avoider with its many subsidiaries in tax haven locations.

I ask the question in the PDF:

How come a UK High Street retailer that is supposedly committed to the UK has a lower current tax rate when compared to its pre-tax profits than a bank with hundreds of subsidiaries in tax havens? And a lower tax rate than another retailer, Tescos, that has attracted considerable attention for its tax affairs? Its rates are, in fact, overall lower than those of IKEA, which is opaque, private, and dominated by activity in tax havens according to at least some reports. It had tax charges of 13.1% in 2009 and 19.3% in 2008.

Some answers are clear. M&S has surprisingly profitable overseas operations — much more profitable than its UK ones. And they seem to be in low tax jurisdictions. The average rate of tax on these operations in 2009 was about 4.4%. What is more as M&S says:

Deferred tax liabilities are not provided in respect of undistributed profits of non-UK resident subsidiaries where (i) the Group is able to control the timing of distribution of such profits; and (ii) it is not probable that a taxable distribution will be made in the foreseeable future.

That’s worrying for its shareholders. As I note:

This means (when compared to the balance sheet ) that about 18% of the total reserves of Marks & Spencer are not now available to their shareholders for distribution as dividends because of M&S's low tax policy. This obviously gives rise to questions about the sustainability of the future income stream the company and the judgement of the management in allocating resources in this way.

But that’s not the whole story — which is hard to find in the accounts. As I also note:

Marks & Spencer will say that the most significant reason for the non-payment of tax is the allowances they are given for spending on capital equipment such as shop fittings, computers, and the like where they make them last a lot longer for accounting purposes than the tax system assumes likely, giving them up front tax relief and so reducing the overall rates of tax. The difficulty with this explanation for Marks & Spencer's is that other retailers, such as Tesco, Sainsbury's and Morrisons do not appear to be enjoying anything like the same relief. This is not to say that M&S are wrong, but it does not appear a complete explanation, any more than pension fund tax consequences are.

There’s nothing, I stress, in the slightest illegitimate about this: M&S don’t need to say more if they don’t want to, and I’m sure they’re finding entirely legal means of reducing their tax bill. But as I conclude:

When this [low tax rate] has happened so persistently and for so long there have to be reasons — and they have to be policy reasons. Based on what’s said in the accounts that policy appears to be that M & S have said “Knickers to Tax”, and they’re getting away with it.

Which is fine for them. But let’s put it another way: if M & S had paid tax at the UK headline rate from 2005 to 2009 (five years) then they would have paid £589 million more in current tax. If it had just paid the tax it declared on its profit and loss account it would have paid £492 million extra.

This needs putting in context: it apparently costs £162 million a year to provide school sport, or about £810 million over five years. M & S could have paid for 72% of that if it had paid the full rate of UK tax on its profits or 60% if it had just settled the total tax it provided on its profit and loss account.

And that is an issue for us all. Ministers might say:

As a Government we’re not interested in large hikes in business taxation.

But the people of this country would like to know we’re all in this together. And it’s still not clear to me that we are.

And that’s all I’m saying.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Have you taken into account that in 2005 M&S won a European court case which gave them £30m tax refund or the 2008 European court case where they got £millions back in wrongly paid VAT?

Because it’s funny that in those years the current tax charge per your analysis has shot down…

@Daniel Walters

Both figures would represent a cash flow, not provisions. I’m referring to the provisions. In addition, VAT is not reflected in the Corporation tax charge, and it is that to which I refer

In other words, I very much doubt these have any significant impact

You can’t just divorce the deferred tax element of the overall tax charge in the way that you have Richard. You comment on capital allowances briefly, but forget to say that the other piece of the tax charge relating to this is in the deferred tax charge. You often refer to the need for investment by business, but forget to mention that when investment is made this generates capital allowances in excess of the early years’ depreciation, generating a deferred tax charge which reverses in later years giving rise to higher current tax in those later years. This assumes that investment is a one off. If a business continues to invest year on year, the excess of capital allowances builds up such that the capital allowances offset the current tax charge. Under current accounting rules, businesses are required to account for this deferred tax regardless of whether it will reverse or not. Capital allowances used in this way are part of your tax compliance definition of paying the right amount of tax, but no more, at the right time.

This explains some of the difference that your analysis seems to suggest is “avoided”. There are no doubt other areas that explain the balance (R&D credits, pension contributions for repair payments to DB pension schemes, etc.)

An analysis like yours is misleading without all the facts and only serves to generate speculation that is often unfounded.

Management have chosen not to repatriate 18% of the cash on the Balance Sheet, so they presumably think that ready access to 82% of their cash is sufficient for now. You disagree. You think shareholders should be worried. M&S will probably disagree with you and the debate rolls on interminably.

The way forward is obvious: reveal your preference, short the shares, and reap the rewards when you are proved correct. With your inevitable profits, you pay CGT – which is likely to be at a rate higher than the 17.2% M&S currently pay. HMRC get their tax in the end (via you), you win big time and the only loser is the clown in the city who bought your shorts by going long on M&S.

Go on. What could possibly go wrong?

The “current tax charge” cannot be comprised solely of provisions. Surely the tax charge is shown net of the £30m tax refund (cr tax charge, dr bank). Where else would it have gone?

If you had bothered to look at Note 24 (Deferred Taxation) to last year’s M&S accounts you would see that most of what you talk about is complete rot.

http://corporate.marksandspencer.com/documents/publications/2010/Annual_Report_2010

Te deferred tax differences arise mostly due to revaluations of the compant’s pension liabilities. The amount of undistributed profits from overseas subsidiaries is fairly unremarkable for a company of M&S’ size and the fact that the effective tax rate is around 28%-30% indicates that you are trying to make a fuss about nothing.

I don’t really see what the problem is. Surely the difference just comes down to claiming capital allowances, deductions and normal reliefs for pensions, salaries etc? The fact that they have operation in “tax havens” is surely irrelevant. M&S in isle of mand and jersey for example is just a normal supermarket – no different from m& s in Norwich or any other uk high street. Are you saying that just because you don’t like us that we should not be entitled to have a branch of uk stores here? And furthermore, under uk law, m&s is able to bring all of it’s profits from here into the uk completely free of uk tax following finance act 2009. A deliberate change by Labour and totally respectable. This contributes to the uk economy and creates jobs – so what’s the problem?

[…] would be easy to say, as some have, that the issues I have raised on Marks & Spencer’s accounts are just a smoke screen. Its total tax charge is almost exactly the headline rate of UK tax, it is […]

[…] would be easy to say, as some have, that the issues I have raised on Marks & Spencer’s accounts are just a smoke screen. Its total tax charge is almost exactly the headline rate of UK tax, it is […]

[…] have produced an updated version of may paper on M & S’s accounts entitled (with tongue somewhat in cheek) “Knickers to Tax” taking into consideration the issues […]

Please see

http://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2010/11/29/sorting-out-the-twisted-knickers-questions-arising-from-marks-spencers-tax/

[…] have produced an updated version of may paper on M & S’s accounts entitled (with tongue somewhat in cheek) “Knickers to Tax” taking into consideration the issues […]

[…] issues, and the potential impact they have on corporate tax planning and behaviour are looked at in a recent report I have prepared. The simple fact is that tax deferred is, in this case, the basis for the payment of a management […]

[…] issues, and the potential impact they have on corporate tax planning and behaviour are looked at in a recent report I have prepared. The simple fact is that tax deferred is, in this case, the basis for the payment of a management […]

Stuart Rose, Chairman of M&S also supported the cuts. So if you or someone you know is facing losing their job as a result of the cuts, please do not spend what money you have in the businesses that think your poverty is suc h a great idea.

http://boycottbigbusinesssociety.blogspot.com/2010/10/boycott-marks-and-spencer.html

Look at it this way: if companies didn’t avoid tax by registering in tax havens, then there would be more wealth in the UK economy which would create even more jobs. Registering in a tax haven, like Boots has in the canton of Zug, siphons wealth out of the UK economy. If you use the infrastructure provided by we other UK citizens’ taxes, you should really not attempt to avoid the requisite amount of tax. What has the canton of Zug contributed to the infrastructure used by Boots? What have the tax havens contributed to the infrastructure used by other companies?

[…] by tax protests this weekend, apparently as a consequence of the blogs posted here entitled ‘Knickers to tax’ looking at M&S’s tax […]