It’s already clear what the Tory defence of the cuts to be announced on Wednesday will be. The Tory think tank, the Centre for Policy Studies, made the approach clear in a report issued this morning in which they say:

The public spending cuts planned by the Coalition only involve reversing, over five years, a comparatively small part of the enormous real-terms increase which took place over the preceding decade.

ÔÇ? In 1999-2000, UK government spending was £343bn, a figure which would, had it simply moved in line with inflation, have reached about £450bn by 2009-10. Actual spending in that year had risen to £669bn, a massive (53%) increase in real terms.

ÔÇ? The spending plans outlined in the 2010 June budget reduce real-terms outlays from a projected £697bn this year to £686bn in 2015-16. Spending then will actually be higher than it was in 2009.

ÔÇ? Interest payments and the political decision to maintain health and foreign aid budgets means that spending by unprotected departments will fall in real terms. But the fall is only 7% — from £523bn this year to £485bn by 2015-16.

ÔÇ? This level of cuts is therefore neither excessive, nor “savage”.

The author of this report is a City based economist: I think we can see where his vested interest lie. But such analysis will, inevitably get wide coverage (the media is predisposed to City opinion) and so it needs to be debunked, straight away. This blog is the precursor for a report that will do that. I’ll mainly use graphs to illustrate my points. The basic data I’m using and it’s sources are available here and here.

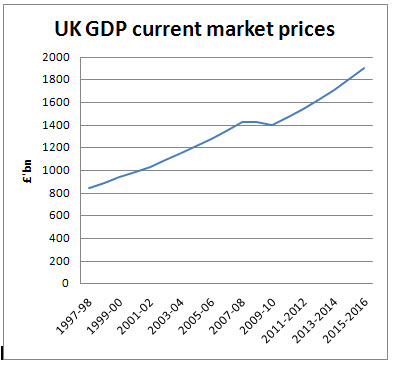

Let’s start with some basics. The UK has not been a static economy. GDP has grown — and is projected to grow. The following is at market prices:

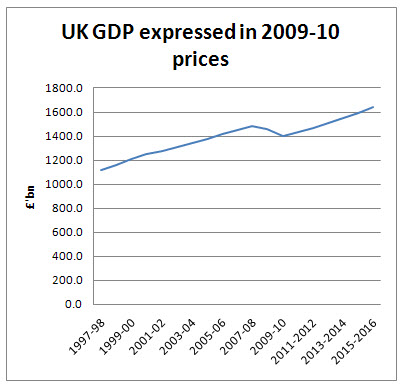

Now of course inflation is a factor, but it’s grown despite inflation. The following is at 2009-10 prices:

Pretty much the same story, just a flatter trajectory.

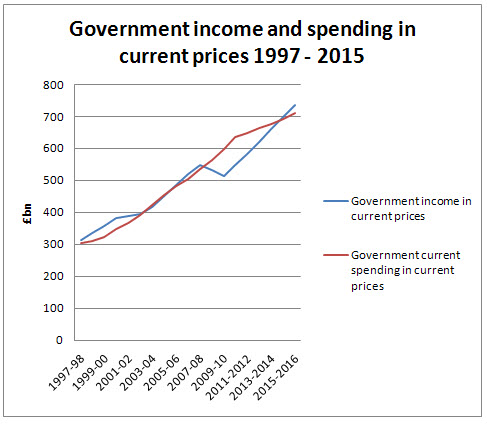

And of course government spending — which I’ll consider in two parts (as one should) split between current and investment spending has also grown:

Sure, that red line has grown — but then so too has the economy! And so too has tax revenue.

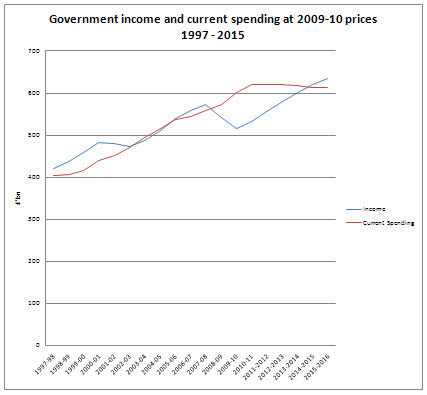

Let’s remove inflation from this:

Unambiguously public spending rose. But so too did GDP! From 1997-98 to 2007-08 inflation adjusted GDP rose by 32.6%. Now I know all the weaknesses in GDP, and with my green leanings I do not believe in growth for growth’s sake. But the fact is GDP as a proxy for economic activity showed we were busy — and pretty much gainfully employed — which i count a good thing. Over the same period government current spending grew by 38.2%. Yes that’s by more than growth — but those from the left argue that’s not chance. we got growth precisely because the state grew. and that was overall good news for us all. The problem was not the growth — it was the reckless response of banks to growth that was the problem.

And note the slightly descending red line from 2009/10 on: the ConDems are cutting spending a little, in real terms. And I agree 0- that’s all they’re planning to do — and yet that does no0t tell the whole story or this blog could end here, as the Tories are doing.

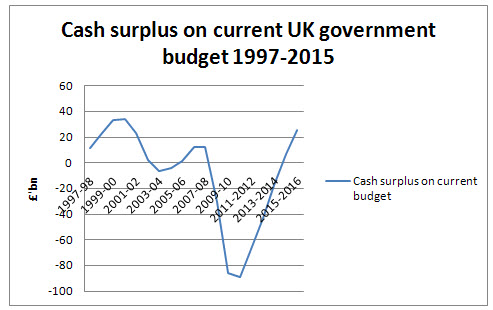

And before we get distracted by discussion of past overspending let’s note this:

Labour ran net cash surpluses on current account until recession hit.

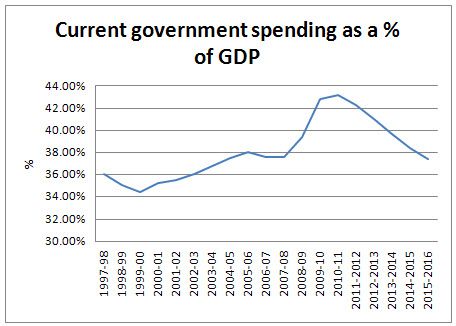

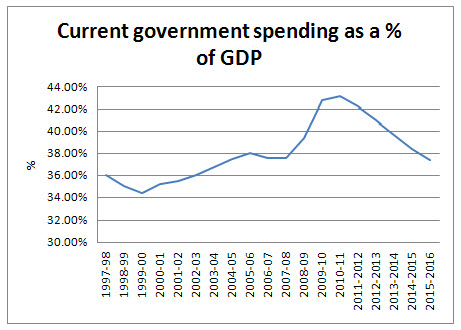

In percentage terms current spending to GDP looks like this:

Now note what the ConDems want to do: they want to seriously cut current spending as a proportion of GDP. Of course, they argue that they’re just restoring the status quo.

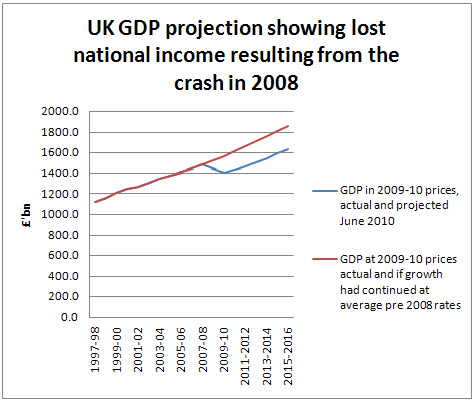

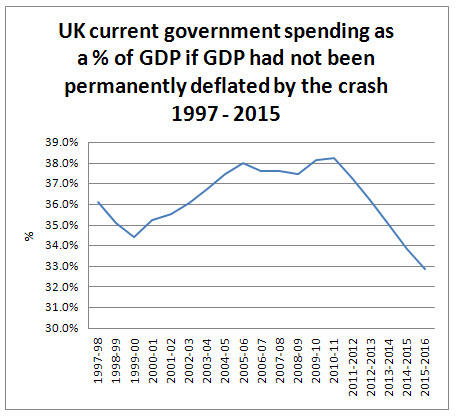

But that’s not true. And there’s good reason why it’s not true. This is explained by this graph:

From 1997-98 to 2007-08 the UK economy grew by 2.86% a year. The ConDem assumption is that from 2009-10 onwards there will be growth of 2.6% per annum. But there is a bit in between. That’s 2008 to 2010. We can’t ignore it. What the graph shows is that between 2008 and 2010 there was a real decline. Instead of GDP growing in those two years from £1,487 billion in 2007-08 to £1,573.7 as it would have done if growth had continued at the rate seen to 2008 it actually fell to £1,403.2 billion in 2009 — 10. All numbers are stated in 2009-10 prices, so in terms of the prices of that year the decline in income from expectation to actual was some £170.5 billion. The fall was therefore 10.8% against potential — a massive decrease. This fall can, of course, be attributed entirely to the banking crash. It was that crash, and nothing else, that created the economic crisis in 2007 and onwards.

As the graph, above, then shows this difference then continues in the planning the ConDems are proposing, and even widens a little so that by 2015-16 it has reached £225.6 billion in current prices — by then 12.1% of potential economic activity.

The importance of this difference between economic activity as it might have been and economic activity as the ConDems plan it to be cannot be overstated. Rather than seek to address the cause of the UK’s financial crisis and restore the well-being of the UK economy, the government (and in fairness the New Labour one that proceeded it) has decided to accept forever the lost potential of the UK economy, and work from a new, lower, baseline determinant for economic activity.

What has to be stressed though is that this is a choice: a choice that is the consequence of three things. The first was the decision made long ago by Margaret Thatcher to base the UK’s industrial strategy on the finance sector. The second choice was to abandon support for all other sectors in the UK economy. The thirds was the decision made, at the behest of the finance sector, to devote all resources dedicated to economic recovery to saving the finance sector resulting in almost no resources going to any other sector — bar, for a brief period, the “cash for clunkers” car trade in scheme. These were not necessary choices: each was an option a government chose to follow, and each has been a mistake. Each could still be changed, with enormous benefit to the UK economy, but the government is choosing not to do so. It is not looking for growth. It is saying that because its chosen policy of support for finance has failed then it will accept the loss, for good, and will abandon the capacity that has been lost as a consequence.

In saying this I stress, the deficit was not caused by government spending running out of control: it remained consistent and under control. The deficit was caused by a collapse in government income. And it is of course a household which sees its income collapse has to react appropriately if it is to survive. The oft quoted Micawber principle (updated her to current currency) says:

Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen pounds fifty pence, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds and 50 pence, result misery

I don’t argue with that. The principle might hold true for the household. It is folly to think it does for the state. The state has three advantages that the household does not have. First it issues its own currency, and can demand to be paid in it. Second, it has a central bank. Third it can set tax rates. The state is therefore in the position to influence its income. Mr Micawber may have suggested that the person overspending should cut their expenditure. The state has the option of deciding to increase its income subject to one condition, and that is that when doing so there are excess, and unused resources available within the economy that can be brought into economic action to generate the new wealth it wishes to create without any significant impact on inflation. That is the case at present: there are more than 2.5 million unemployed in the UK at present with less than 500,000 job vacancies: that is sufficient spare capacity to ensure significant new wealth can be generated given the creation of the right economic environment without any risk of inflation arising at all. And since that capacity exists — as is clearly true — to compare current government spending with GDP that is stated to exclude that capacity is not just wrong, it is thoroughly misleading. Economics is based on opportunity cost, if it based on anything, and the opportunity of using those resources cannot be ignored when spending plans are being considered.

This is especially true when the options the government is appraising are being assessed. We don’t have to compare their plans with the GDP they want to create because they have chosen to remove resources from the economy i.e. because they have deliberately hosen to shrink the economy — as they are. We should instead compare their spending plans with the economy as it would have been and as it could be if the decision — the right decision —m was taken to provide an economic stimulus package to use the unutilised resources in the economy that are available right now and which would, if used, generate the income to pay the costs that have to be faced imposed upon us as a result of the failure of the banks.

If we now compare their spending plans we don’t get this graph, already noted above which seems to show the ConDems are just going to cut back to where things were:

We get this one instead:

Suddenly everything begins to make sense. How can we have a status quo and yet have 25% cuts demanded? How come a state sector the same size in 2015-16 as it was before the crash will need 500,000 fewer civil servants — not by choice but because they had become unaffordable? And how come benefits must be so much smaller and yet apparently be the same in proportionate value terms as they were before the crisis as people like the Centre for Policy Studies seem to be claiming?

The reality is, of course, is that they’re not comparing like with like. They’re saying the percentage is the same — but they are deliberately shrinking the top line to achieve this goal — by refusing to invest in the economy. So the truth is that in real terms — in the terms of the potential the economy has to deliver — which is the potential it enjoyed in 2007-08 and which is the potential it will be denied under the ConDems — they really are imposing massive real cuts on the UK economy — as my graph immediately above shows.

But how do I know they are refusing to invest in the UK economy? There are two ways of saying this. First — their spending lines flat line in real terms , as the fourth graph shows. Labour spent and the economy grew. The Tories are reusing to spend. They still assume the economy will grow — and I will return to that. But they are refusing to contribute to growth.

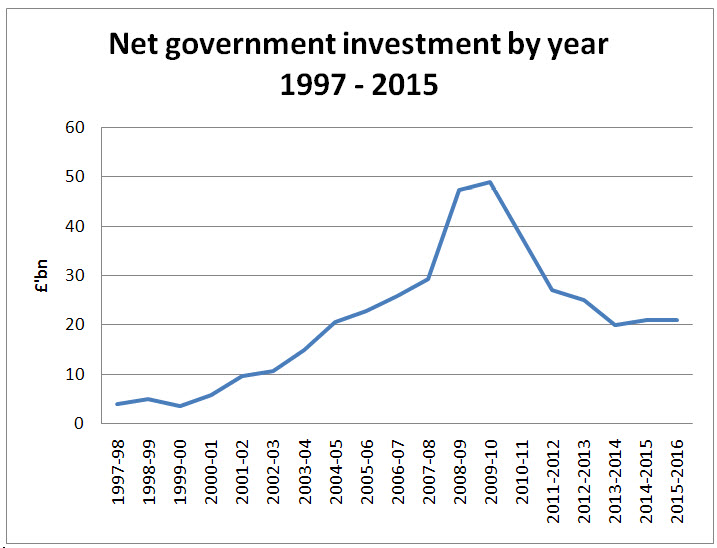

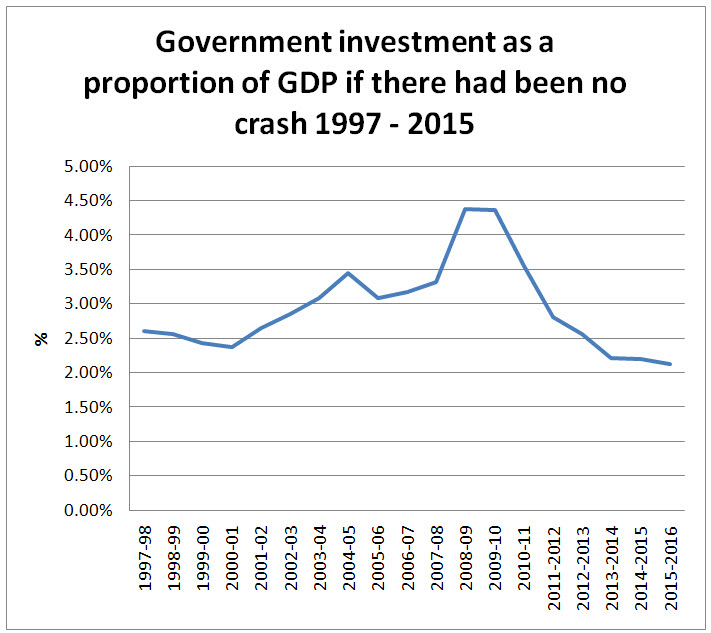

Worse than that — they are actually cutting spending. The second component in state spending, not considered until now, is investment spending. Investment spending net of depreciation looks like this from 1997 to 2015:

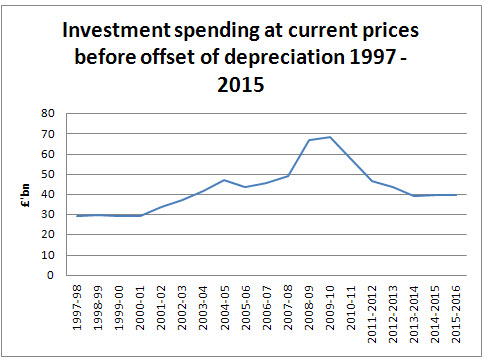

However, this is misleading: depreciation is a residual so real spend before depreciation should be considered, and for the sake of comparison in current value terms, which then looks like this:

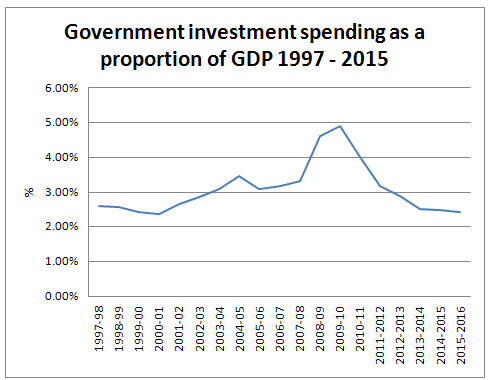

Labour began, as we all know, too cautiously in its first term in office. And then the economy benefitted enormously from its investment spending, which the ConDems will now cut. To understand how much they will cut we need to compare with GDP:

Now it is clear we are going back to the legacy of the Thatcher / Major years.

But it is worse than that. Comparison should, of course, be with the level of GDP the economy has capacity to deliver, which reveals this trend:

Real investment by the government is going to halve over the next few years. And against capacity state current spending is going to fall by more than 5%. More than 7% of economic potential is going to be withdrawn by the government over this period. That’s some £130 bn or so by 2015-16 at current prices. Of that sum not all would need to be covered by tax: investment spending can legitimately and appropriately be borrowed and at least a third of this sum or between £40 and £50 billion could be financed in this way. tax revenues need therefore be no more than £80 billion more to cover this programme.

And what if the government did spend that sum? Well, the economy has the potential by then to be, at current prices, some £226 billion bigger than now. Obviously part of that growth would be the increase in tax spend (but after the extra tax yield on that remember the net government cost would be well under £100 billion pa). The rest would be private sector growth.

Now that is believable private sector growth: growth that will happen because there will be demand in the economy; because the government is investing in the economy, so that in combination there will be demand to encourage real business to invest in the economy, meaning that a virtuous cycle encouraging a trend full employment will be created. And that will, of course, generate substantial tax revenues - at a ratio of about 40% taxation (yes, higher than now — I know — to be financed by more taxes on the well off as explained here) then more than £100 billion will be raised in tax each year — resulting in a current surplus able to cover all borrowing costs with ease — which is the sole criteria for affordability that any lender applies.

In other words — we can do without cuts at all if we spend and restore our economy to its full potential. And that is what the ConDems are deciding not to give us.

In fact they are doing worse than that — because they won’t actually deliver the growth they forecast and as a result the cuts in the deficit they predict as a result of their massive real spending cuts. This is because a government deficit is to a very large degree beyond the control of a government, most especially when a government seeks to control that deficit by cutting spending. This is because the national income accounting identity of a budget deficit is:

Budget deficit = Private Savings minus Private Investment plus Current Account Deficit

In other words (and I am grateful to Malcolm Sawyer of Leeds University for some of this analysis) the deficit is only within the control of the government to the extent it can manipulate private savings, private investment and the trade current account.

The trade current account, we can safely assume is not going to get better over the next five years. With many governments heading for “beggar they neighbour” currency revaluations we’re not going to be a winner on exporting. So that option is out. And financial services won’t contribute as they have.

So we’re down to private savings and investment. Savings are rising right now. The government assumes that will stop. But I see no chance of that happening. Over 90% of savings are corporate — and there is every reason why they will rise. All companies are trying to improve their balance sheets to weather against tough times to come. Banks are providing no new net funding so hoarding corporate cash makes sense. And individuals are doing the same as they see all the satiety nets the state has provided being removed. So there is every chance savings will rise.

This means investment must rise even more. But why will it when there is a declining private and state market to serve and no motivation for innovation from a government intent on withdrawing from active economic activity? The prospect for an increase in investment — when the government is giving the clearest signal it does not believe in it — is in that case minimal.

The good news is this means there will be ample cash available to finance a government deficit. The bad news is it means that the deficit is bound (I mean bound) to grow, not fall. In which case everything will be much worse than noted above and the fanciful idea that the ConDems will rebalance the government books in 2015-16 is absurd.

So what can be done about this? This has been a long blog, and need end soon, simply for technical reasons. The answer is that the government has no choice if it wants to cut the deficit: it must cut saving and it must increase investment. And I have shown that there is a way to do this. In ‘Making Pensions Work’ I have explained that the sum of more than £80 billion a year that goes into private pensions annually is savings, no investment. But force part of that to be invested instead and you both cut savings and increase investment at the same time: a double bonus. Do that to 25% of contributions and the impact is £40 billion off the deficit. Do it to half and it is £80 billion off the deficit: just like that.

Well, not quite. there does, of cou8rse, have to be an industrial strategy to use these funds. And there can be. My colleagues and I have outlined it in the Green New Deal — still the only alternative industrial strategy for the UK anyone has offered. And what is more — because it is green this is not destructive growth, this is sustainable new economic activity.

And that’s the way round cuts — which will be real, sever and immensely damaging the way the ConDems want to deliver them and avoidable in their entirety the way I am suggesting.

It’s no conjuring trick. It’s just good economics, a belief in the UK economy and an industrial strategy we need to get out of this mess. That and politicians who are willing to ignore the immensely damaging advice that the City can deliver — like the Centre for Policy Studies report to which I am responding here.

PS Apologies for typos. I will edit later.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

The reason we got growth was not because the state grew but because credit was ridiculously cheap.

@Allen Bashford

I never heard anyone demanding higher rates at the time

So what should they have been?

And why would that have helped?

Because candidly – I don’t believe you – not one little but

/This comment has been deleted. It failed the moderation policy noted here. http://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/comments/. The editor’s decision on this matter is final.

The comment did not add to debate – and seemingly was not intended to do so

I really cannot see the problem with cheap credit. We need credit for the economy to grow. The problem is that most of that cheap credit fed into real estate which is entirely unproductive. There were siren calls for interest rates to be raised to stop the house price boom. But that is totally the wrong instrument. The real estate sector (actually the land market) is far too lightly taxed.

I really cannot understand why Brown did nothing on this issue when he recognised at the beginning of his chancellorship that the UK housing sector was a big problem – one of the five tests for entry to the eurozone which we failed.

Higher interest rates would have suppressed the boom. Many of the more hawkish members of the MPC were calling for higher rates at the time. It is worth remembering that Blanchflower was calling for lower interest rates way before the crash at a time when house price inflation was 10%. What an idiot. Then he got a lot of wholly unwarranted praise when the crash came – even a stopped clock is right twice a day,

Rates at 6% or so would have been far more realistic in the first half of the last decade.

@Allen Bashford

Respectfully, is the best argument that you can present is that a man who foresaw, accurately, the coming crisis was an “idiot” I think you say a lot more about yourself and your knowledge of economics than you do about anything else

Please don’t bother to comment again – you are clearly not seeking to contribute to debate

Excellent post, thanks. The answer to the crisis is to mobilise unemployed resources (people and cash savings) into building low carbon cities and infrastructure. What’s not to like?

Just as a matter of interest, what actually is the ConDem’s forecast of the sectors where private investment will revive autonomously under laissez faire? And what is the forecast of the city boy & Tea Party types who spew on here? Back to the property bubble?

Richard: would you build the Severn Barrage?

PS It hardly matters that Allen Bashford has been kicked off, because Carol Wilcox’s comment is unanswerable.

Carol’s “I really cannot understand why Brown did nothing on this issue when he recognised at the beginning of his chancellorship that the UK housing sector was a big problem”. Very interesting question. One of the many ways in which Brown failed us, and failed himself. It’s worth pointing out – although this isn’t the whole problem re the land market, I acknowledge – that Brown did desperately urge the building of more houses, but didn’t actually succeed in getting very many built.

Richard,

You are taking the growth rate in the boom as being the trend growth rate. This isn’t a valid assumption. Growth rates in booms are above trend (which is why we call them booms).

It seems that inspectors are able to be enlisted to target benefit crooks, but not tax crooks.

So 1.5 billion will cost 200 x salary + job benefits + credit-agency-fee, and for what return ?

“Some 200 additional inspectors are to be recruited to a new investigation service, which will detect the patterns of fraudulent activities by looking at shared data from government offices and credit reference agencies”

http://news.aol.co.uk/main-news/story/benefits-cheats-mugging-taxpayers/1336256?icid=main|uk|dl1|link3|http%3A%2F%2Fnews.aol.co.uk%2Fmain-news%2Fstory%2Fbenefits-cheats-mugging-taxpayers%2F1336256

Actually, Strategist, I do understand ‘why Brown did nothing’ on the housing issue. Because none of his advisors wanted to listen to the land tax movement. Brown many several submissions before and during his stewardship of the UK economy on the cure for the boom/bust cycle which rests on the land market. He actually spoke at a Labour Land Campaign fringe in 1986. Oh, now I remember being part of a small delegation to speak to ‘Red Ed’ on the subject at the Treasury, when he was chair of the advisors.

One can only hope that Martin Wolf of the FT can keep on pushing for the scales to be removed from eyes on land. But I’m afraid we’re not pinning too much hope on the ConDems, even though there are now members of the Cabinet who understand the issue. There are too many vested interests in the Tory ranks in maintaining the status quo.

Perhaps Alan Johnson will ‘get’ it right away, just like Andy Burnham did, when we get to meet him, but I’m not holding my breath.

Tim Worstall

Please post your analysis.

@JohnM

It’s bizarre, isn’t it?

The madness of this beggars belief

@Tim Worstall

I think you will find that you are wrong Tim

I took an average rate over a period of 10 years and not all can be described as boom years.

I then compared the average rate that they indicated of 2.863% with the rate of the ConDems are forecasting for the next five years of 2.6% per annum

The former is, of course, actual experience. The latter is a forecast. The former indicated real capacity. The fact that banking failed did not mean that capacity did not exist if alternative and sustainable mechanisms for credit were available – as I believe they are.

The ConDem forecast on the other hand is absurd in the extreme: it assumes that despite likely considerable difficulty in achieving export growth, despite the fact that there has been an astonishing increase in the savings rate ratio, and despite the fact that all business is saying that it is cutting back on investment there will in response to a massive restriction in government activity and a withdrawal of credit within the economy plus a reduction in the capacity for consumption expenditure be as a consequence considerable new investment, enhanced export activity when there is no indication as to where or why such sales should be made, and people will reduce their savings when all the indicators to date suggest that in the face of recession people have increased their rate of saving because of the wholly rational fear of the risk that is being transferred to them by government.

Labour delivered, whether you like it or not, a period of sustained growth. I question some of that growth from a green perspective. I think they did fail to regulate banks and that if they had done so the rate of growth might have been slightly lower, but would have been durable. But it was growth nonetheless on the basis of clear underlying increase in economic activity in which government played a clear and active part.

The ConDems are refusing to play a clear and active part and are giving every indicator to the market that it should retract.

Please tell me why in that circumstance my assumptions are wrong and why it is unreasonable of me to compare the coalition choice to withdraw from the economy with the capacity that would exist within the economy if they did not make this choice?

The error is in this bit:

“From 1997-98 to 2007-08 the UK economy grew by 2.86% a year. The ConDem assumption is that from 2009-10 onwards there will be growth of 2.6% per annum. But there is a bit in between. That’s 2008 to 2010. We can’t ignore it. What the graph shows is that between 2008 and 2010 there was a real decline.”

“Trend growth” is, by its very definition, the growth over the entire business cycle. However, what you’re using as your definition of sustainable growth (and sustainable does mean trend, once you extend out over the entire length of that economic cycle), the 2.86%, is only the growth on the upside of the business cycle.

To get to trend growth we have to include the “What the graph shows is that between 2008 and 2010 there was a real decline.”

That’s the only rate we can use for long term planning. Actual growth rates will vary either side of trend, dependent upon whether we’re in a boom or a bust.

So to an extent you’re cherry picking your figures about what sustainable growth rates are. You’ve got to include 2008/09 as well, to give us what trend is.

The only way out of this is to make the claim that you know how to abolish boom and bust: yes, a claim that Gordon Brown made but not one bourne out by reality.

@Tim Worstall

Well it is very clear that your friends on the right have not heard your message. They are assuming a growth rate almost exactly the same as that the Labour Party delivered despite the massive withdrawal from the economy that the government is proposing. Now either that makes their proposals even less likely to deliver, and their prospect of cutting the deficit even more remote – in which case it is very obvious that their proposals on how to do so are completely ill founded and absolutely certainly destined to fail – all you all believe that there is no fundamental sustainable level of development within the economy that can be achieved is wrong. After all, the achievement of potential and the delivery of as high a proportion of capacity as is achievable is, surely, the definition of a successful use of available assets, is it not?Aand yet you seem to be denying this although it is the basis of the hypothesis that I put forward, which shows that this is not the ConDem aim. Why do you wish to endorse a policy that appears to be based on an assumption of significant, inherent and long-term inefficiency represented most graphically by significant, sustained, and socially unaffordable unemployment?

Richard, I’m not doing or saying any of those things.

I am simply stating that you cannot use, as you have done, growth rates in a boom as the proxy for the trend growth rate.

And that really is all I’m trying to get across.

@Tim Worstall

Why haven’t I seen you criticising the Tories for this then on your blog?

Surely some oversight on your part, wouldn’t you agree?

You’ll have to remind me when the edict went out that I have to blog about what interests you rather than what interests me to blog about.

@Tim Worstall

Since you blog about me every day (or so it seems) I just presumed that it was an acknowledged fact but you do not set your own agenda.

But Richard, it interests me to try and spot the errors in your arguments. It’s an intellectual sport.

Writing about intellectual errors made by Tories would be far less interesting: they are the stupid party after all.

And just for the avoidance of doubt, yes, I do very much set my own agenda on my own blog. No outside interference at all.

@Tim Worstall

Well I note that by implication I must be the intelligent party.

Whether or not that is a compliment, coming from you, is a matter for debate – but not one that I am going to allow here.

@Richard

How does the UK’s spending on defense per capita relate to similar countries? What does this mean for defense business? What does this mean for other British industries?

Perhaps answering the above will lead you to a more robust argument.

@Carol Wilcox

as I recall the point of Brown’s five tests was to defeat Blair’s Euro folly. One of the few things he got right. 😀

Cuts? What cuts? They might be intending to reduce the rate of growth in government spending – but its still growing 🙁

@James

If I could understand your comment I might better understand what you’re trying to say – but I can’t do either. In that case your suggestion that may argument might be more robust by listening to what you say is somewhat misplaced

@alastair

I think you claim to be an accountant.

I guess accountants do not need to be economically literate

You aren’t

If you were you would understand how utterly absurd your observation is – as I’ve shown

@Alastair

You’re correct, of course, but the ‘test’ did reveal that we had a problem with the housing market back then and nothing was ever done about it.

This comment has been deleted. It failed the moderation policy noted here. http://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/comments/. The editor’s decision on this matter is final.

@Carol Wilcox

my reading is the only problem with the housing market was requiring the Bank to set interest rates with no regard for house price inflation – and hence to make rates cheap, and hence to stimulate demand, thus leading to a house price bubble. But of course, that was (one of) Gordon’s magic tricks!

Unfortunately my lack of economics knowledge limits me when trying to comment on this post, but I agree with the general argument. Cuts are not the answer and I’m willing to listen to any alternative suggestion. People need to continue to question and voice their arguments. Nice one

@alastair

Monetary policy was never going to be the instrument to control the property/land market, so the remit of the BoE in this respect was quite sound. Why kill the rest of the economy in order to correct the dysfunctional land market? The problem was that Brown did nothing on the fiscal side – a problem which appears to have gone away at the moment, but will continue to cause havoc in the future unless the economics profession gets its act together on the land issue.

[…] did a quite lengthy blog on Friday explaining the absurd logic of those Tories in particular who are claiming thatthere will […]