The realisation is dawning that cuts won’t work. There was an article in the New York Times yesterday by two people whose biogs are:

Peter Boone is chairman of the charity Effective Intervention and a research associate at the Center for Economic Performance at the London School of Economics. He is also a principal in Salute Capital Management Ltd. Simon Johnson, the former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, is the co-author of “13 Bankers.”

They look to be natural radicals as a result. And this is what they said:

With the European Central Bank announcing that it has bought more than $20 billion of mostly high-risk euro-zone government debt in one week, its new strategy is crystal clear: We will take the risk from bank balance sheets and give it to the central bank, and we expect Portugal-Ireland-Italy-Greece-Spain to cut fiscal spending sharply and pull themselves out of this mess through austerity.

But the bank’s head, Jean-Claude Trichet, faces a potential major issue: the task assigned to the profligate nations could be impossible. Some of these nations may be stuck in a downward debt spiral that makes greater economic decline ever more likely.

Prime Minister George Papandreou said this week that Greece needs to see strong investment in order for the austerity program to work. While the government cuts fiscal spending, he said, it needs new private business to employ the dismissed workers so that they are productive, can pay taxes and do not need unemployment benefits.

Precisely. That’s exactly the problem. And exactly as argued here. And here. Like it or not, cut now and the chance of clearing any debt goes for good.

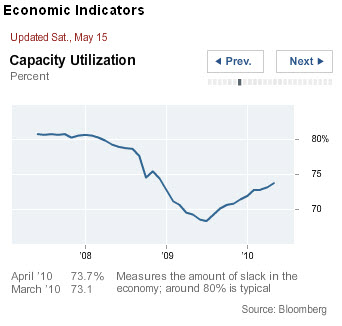

Why? Because despite the absurd logic of the right that the state is crowding out private sector activity the reality is the private sector is simply inactive, and there is no sign that will change. As a chart on the same page of the NYT shows regarding utilisation of US productive capacity:

There’s already excess capacity in the US. That’s true everywhere. No one is going to be enjoying export led growth as a result. So any growth there is going to be is from within domestic economies. And as Greecve has noted, there’s no hope of that if cuts are the only domestic agenda.

It gets worse though. Greece, as the two authors point out is not the worst case scenario. Ireland is, because of its tax haven activity (yes, they do call it one). As they say:

Ireland was one of the first nations to introduce tough fiscal austerity in this cycle — in spring 2009 the government slashed public-sector spending and raised taxes. Despite the cuts, the European Commission forecasts that Ireland will have one of the highest budget deficits in the world at 11.7 percent of gross domestic product in 2010. The problem is clear: when you cut spending you also lose tax revenues from people who earned incomes from that money. Further, the newly unemployed seek benefits, so Ireland’s spending cuts in one category are partly offset by more spending in another. Without growth, the budget deficit still looms large.

Ireland’s problems are, sadly, far deeper than the need for simple fiscal austerity. The Celtic Tiger’s impressive reported growth over the past decades was in part based on its aggressive attempts to help major corporations in the United States reduce their tax bills. The Irish government set corporate taxes at just 12.5 percent of profits, thus attracting all sorts of businesses — from computer services like Google and Yahoo, to drug companies like Forest Labs — that set up corporate bases and washed profits through Ireland to keep them out of the hands of the Internal Revenue Service.

The remarkable success of this tax haven means that roughly 20 percent of Irish gross domestic product is actually “profit transfers” that raise little tax for Ireland and are owned by foreign companies. Since most of these profits are subject to the tax code, they are accounted for in Ireland where they are lightly taxed; they should not be counted as part of Ireland’s potential tax base. A more robust cross-country comparison would be to examine Ireland’s financial condition ignoring these transfers. This is easy to do: a nation’s gross national product excludes the profits of foreign residents. For most nations, gross national product and G.D.P. are nearly identical, but in Ireland they are not.

When we adjust Ireland’s figures accordingly, the situation is dire. The budget deficit was about 17.9 percent of G.N.P. in 2009, and based onEuropean Commission projections (and assuming the G.N.P.-G.D.P. gap remains the same) it will be roughly 14.6 percent in 2010 and 15.1 percent in 2011, while the debt-to-G.N.P. ratio at the end of this year is expected — by our calculation — to be 97 percent, and 109 percent at the end of 2011. These numbers make Ireland look similarly troubled to Greece, with a much higher budget deficit but lower levels of public debt.

Or as I’ve argued for years: there never was a Celtic Tiger, just a giant con trick.

And now Ireland has guaranteed its banks debts, meaning the problem is even worse.

They recommend three solutions. First, winding up existing banks to remove toxic debt from the system — but directors must bear part of the cost.

Second, tough fiscal measures have to be adopted, they say. Personally I’m not so sure. Only spending works when in this mess. But this means I agree with their final prescription: Ireland may have to quit the Euro to revalue. It may be its only way out, they think.

This is the price for being a tax haven: the effective ruin of a state.

Reflect on it.

And then wonder why I’m angry about the waste that has been wrought on so many lives by so few in the pursuit of greed.

NB for more on this read TJN here.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

This comment has been deleted. It failed the moderation policy noted here. http://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/comments/. The editor’s decision on this matter is final.