I knew that re-opening blog comments and writing on tax incidence on the same day was going to attract attention, and it did. Tim Worstall turned up as predictably as a bee round a honey pot to assure me I’d got it all wrong. So did other past regulars, like the falsely named Alex. Interestingly, although the latter clearly sides with Worstall on the incidence issue — arguing that corpropation tax is not paid by companeis he can’t help but reveal the duality of these people's position, saying:

[George Buckley of 3M] is quite right about the transport system and the UK corporate tax regime is probably the most complex in the whole world, with very ungenerous rates of capital allowances for companies like 3M, so his comments are not surprising.

Hang on though Alex — if corporations don’t pay tax who cares what the capital allowance rate is? Companies can pass the bill on anyway so does it matter? Well of course it does — or business and Alex would not make such a big deal of it. The reality is they think this matters for one good reason — because they know they pay the tax. Like it or not that is the true answer to this debate.

But let’s return to Tim Worstall for a moment. Note what he says:

You’re still not getting the point about incidence. We’re not trying to say that the corporation decides to stick someone else with the tax bill. We’re not imputing desire here at all.

What we are saying is that taxing something changes behaviour. Such changes in behaviour can have effects on other people. If those effects on other people make them worse off then we say that they are carrying some of the economic burden of the tax.

For example. Other things being equal, adding more capital to labour makes that labour more productive. More productive labour gets paid more.

If we tax the returns to capital in a specific place then less capital will be added to labour in that place. Labour there will thus be less productive and get paid less. So, some of the burden of the taxation of capital will be carried by the workers in the form of lower wages.

We’re absolutely not trying to insist that managers of corporations try to stick workers with the tax bill. We’re just noting that the imposition of such a tax changes behaviour and thus changes other things as a result of that change in behaviour.

But note three things. First, Worstall sticks to the classic manufacturing model of an economy beloved of economists who think the world is still made up of people making their way to tend smoking stacks. It isn’t like that: most capital is now human, not physical. The model he refers to is a complete fiction of his imagination. Second, note the classic “other things being equal” argument. The trouble is they are not. The EU apart (and Worstall’s living in Portugal whilst working for the anti-EU UK Independence Party is a classic example of this exception to the general rule) labour is very immobile. Some sorts of capital — rather oddly the least productive forms — are quite mobile. But it’s very clear “not all things are equal”. Third, no manager I have ever spoken to recognises the behaviour that Tim describes.

What does that mean? That it doesn’t happen? Or that if it does there may be some other entirely plausible explanation?

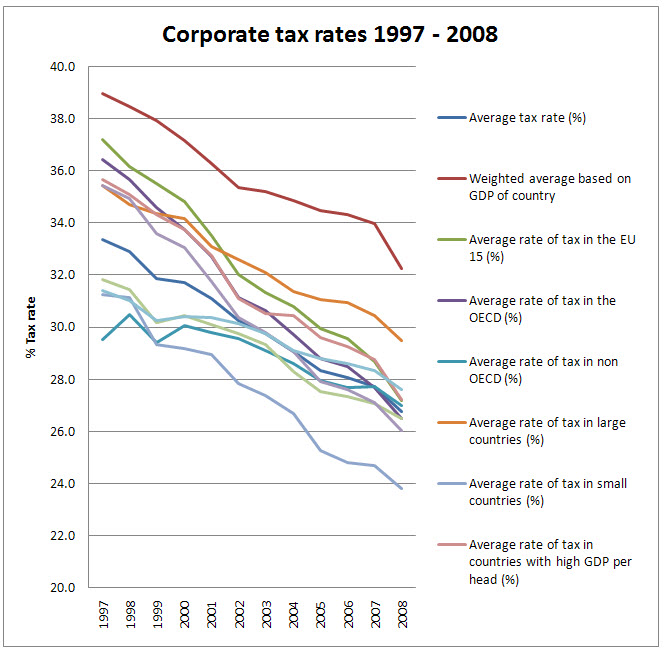

I suggest two things: first, it may not happen. The much beloved Devereux test did, for example, test the very odd hypothesis that when corporation tax went up wages went down. It did not test the alternative hypothesis that wages go up when corporation tax goes down. One has to wonder why. Look at this graph of corporation tax rates in Europe over the last decade or so and wonder which hypothesis would have been more useful to test and then wonder why the wrong one was tested, and what the motivation for that was.

Source data is from KPMG, I did the analysis. Note the number of increases in tax rates and then wonder about the validity of the research findings. Second — note that to do this work Devereux et al assumed the conditions for general equilibrium modelling existed. Someone recently wrote of this “Friedman propagated the delusion, through his misunderstanding of the scientific method, that an economy can be accurately modelled using counterfactual propositions about its nature”. I’d suggest the authors of that research are subject to the same delusion.

In that case let’s assume for a moment that there may be other reasons for noted change in behaviour and return to Tim Worstall who next says:

You keep telling us, for example, that every transaction has to be treated as an “arms length” transaction. As if it were between two unrelated companies, bound only by contracts. Only then can we see whether someone is fiddling the transfer pricing.

This is untrue: that’s not at all how I see the multinational corporation: that’s how the OECD sees it. I see it very differently, as an integrated whole which is none the less rooted in the communities that host its activities. That’s why I propose unitary taxation. In which case I agree with Tim that:

But if at the same time we’re insisting that a multi national is not simply a group of unrelated companies, bound only by contracts, that there is some dynamic unity which is more valuable than the sum of the parts (which is what Coase is telling us is the reason such multi-nationals exist) then we cannot allocate that value to those parts, can we?

In a sense, that’s true. Of course world wide tax for multinational corporations is then the obvious answer, but I think we’re a wile away from that yet, and the reality is that multinational corporations both need to relate to national governments as that is what we have and to pay them — as they’re the only collection agents we’ve got right now. In that case a mechanism to do so has to be found. Arm’s length pricing is one way of doing so — but does not reflect economic realities. Unitary apportionment does seek to reflect how the multinational corporation adds value, and country-by-country reporting provides the data to allow this to be calculated.

Except Tim then objects to the value an multinational corporation creates being taxed at all:

Now, let us, just as an example, take an industry where the multi-national one company form is more efficient. OK. We now know that this form of organisation, being more efficient than the single national companies for, is going to be making higher profits. Not because of any difference in the activity undertaken, not because of anything different in any one location. Purely and simply because of the form of organisation. So, how do we allocate the value of that form of organisation over the different locations? Given that there is nothing related to any location which produces that value?

If we say that because more value is created then each location should get more tax‚Ķ.well, we’ve just decided to tax the more efficient form of organisation more than the less efficient one. Which doesn’t sound all that sensible. We generally think that efficiency should be rewarded, not punished.

So now we come to the core of it: taxing the value multinational corporations create is a bad thing according to Tim. See the incidence argument in that light,and the extraordinarily spurious data that is used to support it and you suddenly see that the economics supports the politics, not the other way round. None of which is surprising — all economics is normative whatever its exponents claim.

But let’s also look at the consequence of this. Suppose for a moment we said that because business does pass on all its taxes to others it should not act as a paying agent for tax (that’s the incidence argument after all). In the UK corporation tax take will be about £35 bn this year, down from a peak nearer the high 40s. Business (or at least PWC) argues that for every £1 of corporation tax they pay they pay £1 of other tax. So let’s cut all the other taxes they claim they pay out as well and exempt them from £70 billion of tax.

What now? Who will pay since we know we need this revenue to fill the budget deficit? Let’s apply a little logical thinking to this. The potential groups who might pay are logically shareholders, supplies to corporations, customers of corporations and those who work for companies. I’ll suggest that’s a comprehensive enough list.

Let’s knock out straight away one possible settlor of the additional tax: that’s the suppliers. They’re corporations too, so that tax won’t stick there as they're now tax free.

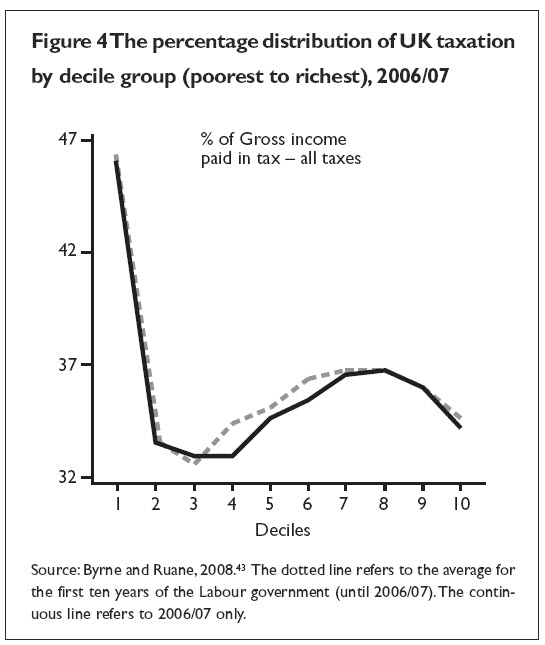

Let’s look at shareholders next. About one sixth of these are UK pension funds in the case of FTSE companies — who pay most tax in the UK. Pension funds don’t pay tax About 40% of ownership of the FTSE (the last time I looked) was overseas — it may be higher now. So put these together and instantly over half of the shareholders cannot or will not have the tax charge transferred to them — at least in the UK. So this income falls outside UK tax entirely. What of the rest — those in the UK? Well, if as the incidence brigade argue these are ultimately individuals then they’re also, because capital ownership is concentrated amongst the best off, those with the lowest overall rates of tax in the UK and the highest rates of tax avoidance. Effective tax rates in the UK are shown here:

As progress into the top 10% increases dividend income rises and effective tax rates fall. Passing the burden to shareholders is therefore regressive at best in the overall tax take and quite probably ineffective with regard to UK investors. I have of course suggested mechanisms to tackle that, but let’s assume the current tax system for now. The fact is shareholders are unlikely to pick up the tab.

So, as Tim argues it’s either customers or labour who will. Customers are most likely to do so via VAT. This is only charged within the UK so customers and labour might be considered as being in the same pool.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies has proposed replacing corporation tax with VAT. They got their numbers wrong, but let’s not worry. As I have shown their logic — which also extends the VAT base, increases the average household food bill in the UK by more than £13 a week. This is incidence at work, and regressive beyond doubt, being almost three times more penal on the poorest than best off in society.

As for income tax? let’s assume that it picks up what VAT can’t - £35 bn or so, and that as the rich apparently always avoid this charge or run away from it this must fall by default on basic rates. So that’s another regressive move.

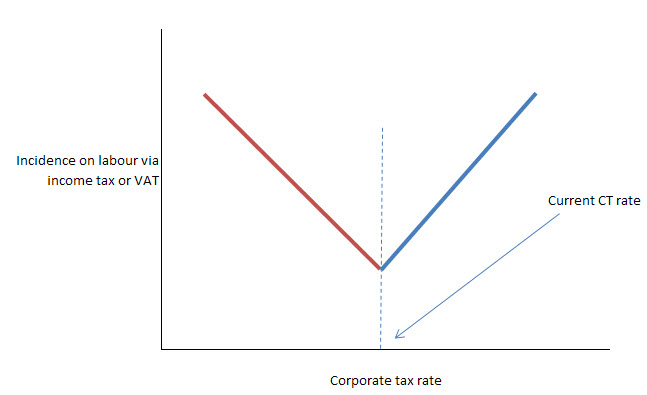

The implication is clear then — abolishing corporation tax has to be regressive. No other possibility exists. And yet Devereux at al argue that its imposition is also regressive. What can this mean? There are three options. One is I am right (as this logic seems to suggest true). Or Devereux is right — but his analysis provides flimsy evidence for it — or we’re both right. Both right? Yes — try this:

It’s a sort of inverse Laffer curve where my argument is to the left of the current CT rate and Devereux et al’s to the right — and by some chance the current corporate tax system happens to be optimal — incidence on labour goes up whether we increase or decrease corporation tax rates. The chance that’s true? Near zero, of course.

So, I’ll stick to my theory. Sure there’s an incidence to corporation tax and the lower the corporation tax rate the higher the incidence on labour, with the reverse also being true, that the higher the rate (within reason) the lower the incidence on labour.

If you disagree prove it wrong, logically, from first principles, using real facts, not models that are so abstracted from reality that they have no relationship to it.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

You could tax dividends upon distribution as a withholding tax. (EU rules are a huge problem, of course, but in principle it would work.) I do not see why this is regressive. In order to get it progressive, the withholding tax would have to be high (50 percent) and reclaimable for low incomes.

And in a perfect world without secrecy jurisdictions you could even do without the withholding tax and tax the shareholder directly…

OK, I’ll have a go.

The issue here is not whether corporation tax profits are a good idea or a bad idea, or whether it is a convenient way of collecting tax. They are interesting questions but for another day.

The incidence questions are:

1) who ultimately suffers the tax paid by the company?

2) is it possible for the company to suffer it separately and distinctly from the individuals (employees, ultimate shareholders, and individuals connected with their customers or suppliers, who may be their own employees or those of their own customers or suppliers).

This has nothing to do about whether a corporation can be greater than the sum of the parts, or whether a corporation can have a ‘personality’ separate from any individual. It can – obviously. But the issue here is whether a corporation can bear and internalise costs separately without affecting any other human being. Can it ‘suffer’?

I argued yesterday that it is physically impossible for a company to suffer anything in the same way humans suffer. A company cannot feel cold, hunger, pain, illness, boredom etc that human beings can. So even if a company can suffer, who cares? It doesn’t get my sympathy in the same way human suffering does and seems to defy the point of economic study – how do we improve the lot of human beings.

So the question is: do higher company tax rates cause human beings to suffer, and if so, who, and by how much?

Some other points for clarification:

1) The ‘suffering’ doesn’t need to happen in the year the tax is paid. It can be deferred and may potentially be suffered years later. But it is still suffered, nonetheless.

2) The ‘suffering’ can indeed be passed down a long chain. Is it possible that a tax rise in Atlanta Georgia affecting Coca Cola affects the guy selling cans of Coke on the side of the road in rural India — several stages down the value chain? I don’t know, but I wouldn’t say it was impossible, no doubt with a time lag.

3) A tax rise is really just another cost shock. Assume in 2009 a company had profits of £100 with a tax rate of 20%, leaving £80 in the kitty for the company to do stuff with. Pay dividends, give pay rises or training, build new plant, buy stock, whatever. In 2010, it earns the same profits, but the tax rate rises to 30%. Now there is only £70 left. This is a hole of £10 that wasn’t there last year. It isn’t an accounting entry – it is a real reduction in cash.

The drop of £10 has to be shared by someone eventually, and ultimately, by human beings. Again, those human beings may be close to the company or many steps removed. That suffering might occur in 2010, or be deferred until some later year (e.g. the company can borrow the £10 for 2010, delaying the pain).

4) I agree, the analysis required to find out who suffers and by how much is hugely complicated, not least due to delays in time, the many steps removed, and also trying to determine whether the suffering was actually caused by the tax rise, or by something else. But just because it is hard to work out who has suffered and by how much doesn’t mean no suffering has occurred (or will occur).

To turn the issue on its head: is it plausible to say that the tax rise in the example above won’t affect any human being at all ever? Can the company to somehow permanently internalise it without making anyone worse off?

If so, then that will be the greatest discovery known to man, and surely worthy of a Nobel Prize. I would surely vote for very high company tax rates.

I accept it is also difficult to study this issue given that the world has mostly seen a reduction in corporation tax rates over the past decade or so, so it is difficult to find real life recent examples.

However, why can’t tax rises be treated as just another cost shock — much like the rise in the cost of a major raw material? How do companies share out the pain then? Can they internalise it indefinitely without inflicting pain on any human being?

The logic I use in working out who bears most of the pain of a cost shock is that it is usually the group least able to do anything about it. You thought so yourself in your recent post about credit card costs being passed on to the less-well-off. Our logic is the same here.

So who bears it? Shareholders in a plc can easily sell their shares, those in a private can’t do so as easily. Highly paid workers with rare skills can easily find new jobs, low paid workers with low generic skills can’t. Customers of a monopoly have to wear price rises, customers in a competitive industry can shop elsewhere. So it depends.

A question is: where do the low paid workers fit into this? If the burden of the cost shock is passed on to them, how easy is it for them to move? If the answer is ‘not very’ then I suggest it is pretty likely they will wear a fair bit of the burden.

In considering whether labour has borne any of the brunt of a cost shock, looking at wage rates is just one part of the picture. Wages themselves are sticky – in my example above, the £10 drop is unlikely to mean the wages for the workers will drop, at least in the short term. But it may mean less in the pot (and therefore budget cuts) for the company to pay for the following:

Training (making it harder to get the skills to get promoted or hired elsewhere).

Recruitment (which means those of us working here have to work longer hours to do the work when there is a vacancy, reducing the return for our labour).

Expansion (i.e. fewer promotional opportunities).

Perks, overtime etc.

Finally, the low paid workers aren’t just workers. They can often be shareholders in a company (through their pensions) or its direct or indirect customers. So the burden can be passed onto them in their other capacities.

In considering the incidence of a particular tax it is necessary to consider the incidence of the tax which might replace it or the withdrawal of a service which the tax funds. (I think Richard has already said this.)

As a lot of this is addressed to me please allow me to respond.

“(and Worstall’s living in Portugal whilst working for the anti-EU UK Independence Party is a classic example of this exception to the general rule)”

I do not work for UKIP. I used to work for UKIP. I worked in London for the party in the run up to the euro elections. That’s all I was ever signed up to do. So perhaps that little giggle can be put to rest. Secondly, I’m afraid you’ve got a tad garbled as to what UKIP is about. We’re against a specific political system, the European Union, not against the continent of Europe nor the people or countries of it. Saying “Worstall lives in the EU but he’s against the EU, ho, ho”….well, that’s got the same logic as saying that Richard is against the Tories but soon (well, most likely) he’s going to be living under a Tory Government. Ho, ho. Does Richard have to move out of the country because he doessn’t like the system of government?

No, of course not. Nor does Worstall have to deprive himself of the joys of living in Portugal because he doesn’t like the European Union (nor did I have to deprive myself of the fun of living in Russia despite not liking Yeltsin’s government, nor the US under Clinton). And yes, English people have been living in and moving to Portugal for many centuries….just look at the names on the Port bottles next time you’re in the supermarket.

Right, on to more important matters.

Re tax incidence. I sketched an explanation there, not gave an academic paper on it. Look, Richard, I know that you really don’t like this idea but please, try to listen to what is being said would you? This isn’t an invention of Mike Deveraux for goodness sake. One of the major papers on it came from Joe Stiglitz for crying out loud. Yes, that Nobel Laureate that you rather like when he’s talking about other things. The Wikipedia page is pretty good on it:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tax_incidence

If you want more papers on it might I suggest Googling “incidence of corporate taxation”? There are a number of good papers there.

You’re also missing entirely the point of the whole argument.

“Suppose for a moment we said that because business does pass on all its taxes to others it should not act as a paying agent for tax (that’s the incidence argument after all).”

No, that isn’t the argument at all. What we want to know is who is the tax burden passed on to?

We’re fully aware that corporations are convenient places to collect tax, that this way you get to collect tax from overseas shareholders and all of that.

Imagine two scenarios. Both start with the idea that we want to tax returns to capital. For we’re not happy with the idea that capitalists and rentiers get to live tax free while those who live from the sweat of their brows have to pay for all the government that keeps the capitalists and rentiers safe and not hanging upside down from lamp posts as the result of an irate mob. This would be roughly your view Richard I think and it would also approximate to my own view. So, our two scenarios.

1) We examine tax incidence and find that all of it, or perhaps even just the vast majority of it, the economic burden, is carried by shareholders and owners of capital in the form of lower returns to capital.

2) We examine tax incidence and find that all of it or the majority of it is carried by labour in the form of lower wages.

If 1) is true then our tax is doing what we want it to do and everything is hunky dory. If 2) is true then we’ve a problem. For while we intend to tax the returns to capital in fact we’re not, we’re taxing the returns to labour. Just what we didn’t want to do, for we already tax that anyway.

The importance of the argument about tax incidence is not that it happens: it is who carries the burden. And if it’s not the people we’re aiming the tax at then we rather need to change what we’re doing, don’t we?

Here’s the OECD:

“The section on tax incidence concludes that capital as well as labour and consumption

may partly bear the corporate tax. In addition to the Harberger model, the incidence of the

corporate tax is discussed in an open-economy. It is argued that the easier it is to substitute

foreign production for the home-country’s production and the more mobile is capital, the

lower is the burden of the corporate income tax on capital and the higher is the burden on

the more immobile production factors such as labour. However, if capital is less substitutable

(less internationally mobile), then the corporate tax burden will fall partly on capital”

http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/40/58/39672005.pdf

Richard, you talk to people there….try asking them about it all. Don’t take my word for it, get the news from people you already trust. And please don’t keep trying to prove it wrong from first principles. This has been thought about by a lot of very bright people for over a century now. The economic burden of corporate taxation goes somewhere….and the more open the economy the more likely it is that it is onto labour. So, in open economies we might want to think about curbing our enthusiasm for trying to tax returns to capital through a corporation tax for it doesn’t work.

“So now we come to the core of it: taxing the value multinational corporations create is a bad thing according to Tim.”

No, that’s not what I say. Rather, that there is extra value created simply because of the legal form….a multi-national as opposed to a collection of independent companies. It’s that extra value that I don’t see as being taxable by any particular locational jurisdiction.

As to you proposing unitary taxation: but you’re not. You’re arguing that the activity which takes place in each jurisdication should be taxed. That’s the opposite of unitary taxation. California has unitary taxation of corporations. They look at worldwide profits, look at the percentage of the workforce, or sales, which occur in California and then ask for that percentage of worldwide profits. That’s unitary taxation.

“So, I’ll stick to my theory. Sure there’s an incidence to corporation tax”

Excellent. And all the papers that have been written about it show that the majority of that incidence, in open economies, falls upon labour. Which isn’t what we’re trying to tax at all. We’re trying to tax returns to capital, remember?

Corporation tax as it is is indeed largely regressive. Thus the removal of it is largely progressive.

Now there is a way out of this. That one world taxation system for companies that Richard says we’re not ready for above. With that, then yes, corporate income taxes would fall upon capital. But without that they won’t.

This point is well made here:

http://www.cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index=304

We could also try other measures. For example, not impose corporation tax (this would not affect royalties for minerals etc of course) at all. But simply deny thatn there is any difference at all between returns to capital and returns to labour. Income is income and you pay the same tax rate on it whatever the source.

Perhaps that will work and perhaps it won’t….but the important point that we’ve already got to acknowledge is that if our intention, in taxing corporate profits, is to tax returns to capital then that system doesn’t work in the world as it is. For the majority of the burden of corporate income taxes fall upon labout. Exactly and precisely what we’re not trying to do.

Just to repeat, once again. The problem is not tax incidence. It’s who the incidence falls upon. If it’s labour then corporation tax isn’t doing what we want it to do, is it?

@Tim Worstall

OK, let’s agree – let’s leave the quipping aside. I can if you will.

Then let me deal with some of the issues you raise here before I write another blog sometime soon on the bigger issues.

First – I wholly understand your point “The problem is not tax incidence. It’s who the incidence falls upon. If it’s labour then corporation tax isn’t doing what we want it to do, is it?” I have not denied corporation taxes have incidence consequences.

But I also note you have not addressed the point I make – that if removing corporation tax would undoubtedly increase incidence on labour and reduce it on capital then it is working, at least in part. How can you disagree? The CBO and OECD sources you quote say the same thing and note the issue is not resolved.

I will return to this in more detail, later though.

Second, I wholly understand unitary taxation. That is exactly what I am supporting, lock stock and barrel. See my paper http://www.taxresearch.org.uk/Blog/2007/09/14/tjn-propose-unitary-taxation-for-the-uk/. We appear to agree.

But unitary taxation requires data to achieve its goal. That’s exactly what country-by-country reporting is designed (amongst other things) to deliver. What are we disagreeing about?

Please elaborate more on the alternative tax you are actually suggesting if not a unitary one. The CBO paper is non-specific in its conclusions.

But then – because it seems to me you’re actually concurring with a lot of what I have said in the above comment – or at the very least you’re misreading me and so quibbling where there is no issue at all, as on unitary tax – please in that case suggest why my logic on the removal of a corporation tax noted above is wrong and why it isn’t at least better that we collect some tax on capital rather than none at all, because let’s be clear – unitary taxes also have incidence issues.

I think the real issue is not the rate of corporation tax but what actually gets taxed, most multinationals and private equity run firms manage to show zero income as transfer pricing and playing around with funding offshore and royalty charges mean all the real profit gets spirited overseas to a zero tax environment, the most effective thing the HRMC could do is say we won’t allow any loan interest paid to a non UK bank to be offset against tax , any other payment is subject to a 30% withholding tax , any royalty or fee for professional services paid offshore likewise 30% withholding tax, this creates a level playing field for companies who want to access the domestic uk market. we do this with dividends so why not do the same for payments for offshore services ( outsourcing ) or royalties and debt payments.

“I have not denied corporation taxes have incidence consequences. ”

I agree that you haven’t now. But certainly my memory of your statements in the past is that you have. Which is why I’ve gone on and on about it over the past couple of years. But now that you agree that there are incidence consequences we advance the debate.

“But I also note you have not addressed the point I make – that if removing corporation tax would undoubtedly increase incidence on labour and reduce it on capital then it is working, at least in part. How can you disagree?”

Because I’m trying to make a very different point. The general man in the street response to corporate taxation is that, yes, of course companies must pay their fair share. Indeed, we see this very point being made all over The Guardian and even, as a rhetorical measure, by yourself, John Christiansen and Action Aid, War on Want and so on. But now we agree that we’ve this incidence thing. It isn’t the corporations bearing this burden. It’s some combination of consumers, shareholders and workers.

And as Joe Stiglitz pointed out, that incidence can be (can be, not necessarily is….and I use Stiglitz to avoid your antipathy to Mike Deveraux) higher than 100%. That is, the burden of lower wages on workers can be more than the entire tax amount raised.

If we then assume (not unreasonable assumptions although clearly not perfect) that the amount raised in tax, say, £10 just to have a number, benefits the workers by £10 but the raising of the tax reduces worker income by £11 then by not having the tax at all we’ve made the workers better off.

Perhaps I should explain a little more here. One of the interesting things about tax incidence is that it is not true, either in practice or in theory, that the burden of the tax has to be the same as the amount of tax raised. It’s entirely possible that the incidence is less than the tax raised: excise duties on tobacco for example. The benefits in longer lives to those dissuaded or limited in their smoking by the tax hugely outweighs the actual amount of money raised in the tax (umm, let me relax that a little. It’s highly likely that this is so). A carbon tax at the social cost of emissions might also qualify here.

But we can also have in theory (as Stiglitz showed) a tax where the burden is higher than the amount raised. Even the burden on one particular group, leaving aside the effects on other groups. Whether this is actually true, instead of theoretically possible, in the case of corporation tax is an empirical question and one not solvable purely by appealing to first principles. It requires detailed study of the real world…..something I am not equipped to do thus I rely on papers published by others to do so.

So, if the burden on the workers is £11 for £10 raised in tax, by not having the tax we’ve made the workers better off, at least in the first iteration.

We can go on and make all sorts of further assumptions: that government spending is so beneficial that £10 of it is worth more than £11 in the workers’ pockets for them to spend as they wish. You’ll not be surprised to hear that I don’t, except at very low levels of government spending (like a criminal justice system sort of minimal state) believe this to be true. Or I might point out that there is inevitably a levy secured by the bureaucracy in such spending: meaning that £10 of tax money being process leads to £9 or £8 of benefit to those it is spent upon. Or I might point to deadweight costs….but that debate is going to get very messy.

So back to the theoretical position that the burden upon the workers is higher than the amount raised in tax. By not having the tax at all we make the workers better off than by imposing the tax.

Yes, even if that means we don’t tax the returns to capital, even if we don’t have that spending funded by that tax. *Still* the workers are better off by the tax not being levied and the services not being provided through taxation funded spending.

I know, it seems very odd, but welcome to the wonderful world of tax incidence. There are times when we can make a group better off as a whole by not taxing.

As to unitary taxation: that’s a maze I don’t really want to go down. I’d rather stick with this one point about the incidence of corporate taxation at least until we’re done with that.

Just to reiterate the point that I think we’re at. We know in theory (because a Nobel Laureate has told us so among other things) that corporation tax can lead to the burden upon the workers being greater than the total sum raised by that tax. We’re not sure that this is true in practice although some certainly tell us that it is. Even if taxation funded spending produces 1:1 benefits as against the benefits provided by money fructifying in the pockets of the populace we can thus make the workers better off by simply not imposing the tax at all. Yes, even at the expense of not taxing returns to capital and of not having the taxation funded spending.

So, what we need to do now to measure the benefits of such corporate taxation is work out whether the burden does indeed fall upon the workers (I think that’s proven at least in part) and if so, how large is that burden? That last requires good empirical research. At which point the burden of proof would seem to fall upon those promoting higher corporate taxation. Prove to us that the effects of it are not greater than the benefits derived.

Tim

Shall we leave Stiglitz out of this? I don’t think he walks on water. Chapter seven of Free Fall is good for reasons you won’t like but Chapter 8 is weak. He’s not beyond criticism.

And now, let’s again move to the core issue. You say:

If we then assume (not unreasonable assumptions although clearly not perfect) that the amount raised in tax, say, £10 just to have a number, benefits the workers by £10 but the raising of the tax reduces worker income by £11 then by not having the tax at all we’ve made the workers better off.

can you prove your assertion – without recourse to models that basically assume the conditions for general equilibrium theories hold true? We know they don’t.

Note also the OECD and CBO do not support your assumption.

Next you say:

So back to the theoretical position that the burden upon the workers is higher than the amount raised in tax. By not having the tax at all we make the workers better off than by imposing the tax.

Yes, even if that means we don’t tax the returns to capital, even if we don’t have that spending funded by that tax. *Still* the workers are better off by the tax not being levied and the services not being provided through taxation funded spending.

Hang on – who has done the work linked to the use of tax revenues – show it to me? You’ve just asserted again, without evidential support.

Finally:

Just to reiterate the point that I think we’re at. We know in theory (because a Nobel Laureate has told us so among other things) that corporation tax can lead to the burden upon the workers being greater than the total sum raised by that tax.

A Nobel Laureate was behind LCTM. It did not stop it failing, did it? You really do have to do better than that. It’s abundantly clear that because something might happen does not mean it does happen. Many Nobel laureates have been just plain wrong. The burden may be very, very much less. Just try answering the points I have raised above in the original blog. Show why I’m wrong.

And then answer me two more things. 1) how would you tax capital 2) where do you think you’ll find the data to prove your point?

If you can’t, my logic prevails in the real world.

Richard

Richard, I pepper my comment with the point that incidence can theoretically be larger than the tax raised. Whether it is or not is an empirical question, not a theoretical one. As such it has to be answered in an empirical manner. It requires collecting evidence, not a working out from first principles.

As to incidence or the burden possibly being higher than tax raised. That’s easier.

So, foreign exchange trading. As you write in your report (where you are drawing upon an empirical paper by someone else rather than calculating the numbers yourself….see, we can indeed use the work of others to make our points) bid&ask offers appear to be …well, rather than my opening up the paper again let me just construct an example. To show the logic.

Bid/Ask spreads are say 2 bps. Actual turns (many market makers bidding 2 bps around and about the mid point) are 1 bps. Fine. Now we introduce a 0.5% transactions tax.

So, I conduct an FX transaction and under the old rules it costs me 2 bps (again, just to show the logic). Under the new system it costs me 2.5 bps. Spread plus the tax.

But does it? You’ve told us that the market will fall in size by 25%. There will be less liquidity in that market as a result of the tax. Less liquid markets have wider spreads (yes, this is obvious, liquidity and competition are the same thing).

So, spreads will widen.

Now it doesn’t matter for the logic here how much the spreads widen, only that they do.

If spreads don’t widen then the tax itself is the economic effect: that 0.005%, 0.5 bps. But if spreads widen to, say, 2.5 bps then we’ve got a burden of the tax of 0.5 bps plus the tax of 0.5 bps. The total burden of the tax is 1 bps, twice the amount raised.

Imagine, horrors, that spreads widen out to 10 bps (I’m not saying that they will, just that it is possible. Spreads were 10 bps only a decade or two ago) then we’ve got a burden of the tax nearly 20 times larger than the revenue raised by the tax.

Please note that I’m not trying to adress anything other than this one single point. The burden of a tax can be, as a result of changes in behaviour caused by the tax, larger than the tax revenue raised.

*Whether* this will be true of any specific tax in a specific market is something that requires study of that tax and that market. It’s an empirical question.

Note that none of the above depends upon general equilibrium nor indeed any macro economics at all. This is straight micro.

It’s also not specific to foreign exchange taxes, transaction taxes or any of the arguable benefits or costs of them, nor does it even depend upon the incidence of a tax.

Some taxes, some times, have costs larger than the revenue they collect.

Do we agree on that?

@Tim Worstall

You’re not winning Tim. let me explain why. First you say Richard, I pepper my comment with the point that incidence can theoretically be larger than the tax raised. Whether it is or not is an empirical question, not a theoretical one. As such it has to be answered in an empirical manner. It requires collecting evidence, not a working out from first principles.

That’s lame for two reasons. First, all economic reasoning starts from first principles. Second, as you well know, there is no data at all that can prove your point: the jury is out. In that case we have to work on different bases. I have offered one. you have not responded. You are losing in that case.

Second, you argue that burden of proof would seem to fall upon those promoting higher corporate taxation. Prove to us that the effects of it are not greater than the benefits derived. I guess you therefore accept the taxes we have are OK. That’s a win.

Third, why is the burden of proof on those who from a priori logic can prove their case when those who want to use empirical data cannot?

Fourth, you should note the 5 Rs of tax. These are that tax is used to:

1) Raise revenue;

2) Reprice goods and services in pursuit of social objectives (tobacco, alcohol, carbon emissions etc.);

3) Redistribute income and wealth;

4) Raise representation within the democratic process because tax is the consideration in the social contract between those governed and the government; and to facilitate;

5) Reorganise the economy through fiscal policy.

In other words in four out of five cases behaviour is more important than revenue – in which case cash flow need not be the criteria for raising a tax. You have your logic wrong. And unless you can price the externalities no empirical data can prove the argument, ergo we fall back on my logic again.

Which brings me to your long point on FTTs: tell me what the real cost of a 10bp margin is and who will really lose. Prove it using data. You won’t be able to do so because the social disruption of the socially uselsss activity undertaken at 2bp can’t be priced – but it real nonetheless

The inability to secure sufficient data is not a cause for inactivity: indeed, it may be just the opposite. It may say the activity is too complex and therefore risk laden to be tolerated.

But in any case – please deal with the points I raise in my example in the blog entry and address them properly or you are clearly ducking the issue – and all will see that.

Richard

[…] trots out his five Rs of tax in an interesting thread where he’s sparring with Worstall. These are supposed to spell out […]

“Which brings me to your long point on FTTs: tell me what the real cost of a 10bp margin is and who will really lose.”

OK. Taking the numbers you’ve given me here.

Before the tax we have a 2 bps margin. We add the 0.5 bps tax. We then have a 10 bps margin. Those are the numbers you’ve given me.

Take one more number. The approximately $30 billion you say such a 0.5 bps tax will raise from the FX market.

Margins have been raised by 8 bps as a result of the tax. That is 16 times the revenues from the 0.5 bps tax. That is $480 billion.

Note that this is indeed already including the effect of lower transaction volumes: for your estimate of the tax revenues already includes this.

All users of the financial system are thus carrying a burden of $510 billion (the tax plus the rise in margins) in order to gain $30 billion in tax revenue.

The losers here are the users of the financial system by some half a trillion dollars. Those who gain, well, it looks to me like the bankers actually. They’ve got $480 billion in higher margins to play with.

The net effect of this tax therefore is a huge transfer from us the consumers of financial products to the providers of financial products.

Doesn’t sound what like any of us is trying to do really. Certainly the outcome is exactly the opposite of what you say you’re trying to achieve.

I should note that I don’t think that a 0.5 bps tax will increase margins to 10 bps….not that far. But the logic stays the same at any widening of margins, only the sum of the burden changes.

@Tim Worstall

Thanks Tim

What you prove is the impact will be very small

In fact it will be at most the tax margin – except as markets are so volatile, as I’ve repeated often enough, this will reduce volumes and this will in turn save more cost than the extra charged leading to no extra incidence but to a fall in bankers’ pay

My case is proven in that case – and your logic as noted above is o=very obviously wrong

Good of you to agree

Richard

“What you prove is the impact will be very small

In fact it will be at most the tax margin – except as markets are so volatile, as I’ve repeated often enough, this will reduce volumes and this will in turn save more cost than the extra charged leading to no extra incidence but to a fall in bankers’ pay”

Forgive me here but you’re going to have to explain that comment one point at at time for I can make neither head nor tail of it.

How do you get from half a trillion doallars to the effect being very small?

@Tim Worstall

Tim

You say, quite rightly of course, that the adjustment for a o.5 bps tax will not be a widening margin by 8bp – actually that data came from you on Freethinking Economist – not me – so the adjustment will be much smaller than you suggest above

Then you just have to open your mind and follow my logic. That is simple: the volume of trades is far bigger than needed for any real transactions

Those that will cease will be the pure speculative ones from banking. So bankers will not be needed, so their pay falls, significantly individually as some will cease to be bankers and as a collective remainder as demand for them falls. That’s pure micro stuff Tim, don’t you agree?

The cost for other users will rise, but because total volumes traded will be smaller, including for them, overall they will save (read the report for the whole logic). The condition is that if the volume fall is 25% the tax is not more than 1/3 of the remaining margin.

As such their overall third party cost will not rise so they suffer no incidence

But bankers will bear an incidence

Plenty of others have got the logic, I’m not sure I need to repeat it again

Richard

“The condition is that if the volume fall is 25% the tax is not more than 1/3 of the remaining margin.”

That is indeed the condition for the system as a whole, yes. But that’s an assumption that you are making, that margins will only widen by that much. In fact, if I remember the numbers from you paper correctly, the assumption necessary there is that margins will only rise by the amount of the tax itself and no more.

Average margins on a deal (ie, spread in the market, not spreads from an individual dealer) are 1 bps. Tax of 0.5 bps …one third….thus total spread cannot be higher than 1.5 bps.

So your assumption is that margins don’t in fact increase at all. That a 25% drop in liqudity doesn’t change margins. Which is an amazing assumption to make. Having flicked through your sources I don’t see anyone making that assumption at all. Indeed, I see people making the opposite, that margins will increase as a result of the addition of a tax.

“The cost for other users will rise, but because total volumes traded will be smaller, including for them, overall they will save (read the report for the whole logic).”

This also seems incorrect. For the system as a whole (if your assumption above holds) yes. But we’ve not got the same people in the system, have we?

25% of the people have left the system: 25% of the trades have gone. So those 25% are gaining from the tax. They not only don’t pay the tax they also don’t pay the spreads.

The other 75% of the people/trades now bear the entire cost of the system. The tax and the spreads.

So even if the total costs of the system are the same we’ve moved the costs of the system off of short term speculators (those 25% the tax dissuades from trading at all) and onto the 75% remaining: which of course includes all of those who need to trade FX for trade, hedging and other “real” purposes.

We’ve still got this tax incidence thing and we’re still putting the incidence where we don’t want it, on “real” activity rather than speculation.

Even if margins don’t expand. An assumption which I regard as wholly unwarranted.

Tim

I did not suggest margins are 1bp – it’s very clear not all are

I think 2bp is much more likely

My conditions hold in that case

We can agree to differ – I don’t think we’ll get further on this

But you assumption re the 75% is just wrong – you’re assuming each trade is discreet and separate – which is untrue – most trades are part of a large pattern of trades by a very small number of players. In which case you logic is wrong and mine works, as you acknowledge in that case

And the cost of the system has fallen dramatically is the point I make that you refuse to acknowledge – the demand for bankers falls and their price with it, which reoslves that issue

In which case my logic works

I think you’re very close to agreeing

Richard

“My conditions hold in that case”

No, they still don’t. For we’ve no evidence other than your assumption that margins will not change by more than the tax.

“And the cost of the system has fallen dramatically is the point I make”

This is true only if your assumptions about margins hold. Which is something that needs to be shown not assumed.

Further, even if that condition does hold we’ve still got the fact that different people are paying the costs. Which is, again, incidence.

Tim

I really think we are coming back to your lack of comprehension about rick and uncertainty. Keynes knew this difference. Risk is of course calculable. Probability can be attached to it: a percentage can be attributed. Uncertainty is not calculable. It is dealing with the unknown. As Keynes argued, ordinal probability lies between the two — the possibility of the event exists, the likelihood is not known. Probability cannot be attached to it. Empirical economics deals in risk. It is however the thing that humans are remarkably unable to deal with. Massive amounts of research shows that people really do not understand 5% risk, although they can comprehend a conditional likelihood of 1 in 20. That might baffle an economist, but then so does ordinal probability and uncertainty baffle most economists — which is why there are so few true Keynesians. The reality is, as Keynes knew and as behavioural economists know, it is only the simplest of issues that can be handled empirically. Complex issues — like the curiously Keynesian reality of living with the paradox of assuming we’ll live forever, as we have to if we are to behave in society, whilst knowing we will inevitably die — those are way beyond the comprehension of economists, and that’s only because they’re in the range of ordinal probability. Uncertainty is totally beyond most economist’s modelling altogether. So why use data in that case when it is clear that the human condition requires we use logic, some of it even intuitive? That’s the reality of living and precisely why the sort of economics you are demanding of me cannot deliver results for society — as has been emphatically proven over the last few years.

The change in the margin that will result from this tax cannot be demonstrated except by introducing it. There will be a change. We cannot say how much. That’s ordinal probability

So we make assumptions. We consider if they’re plausible – I contend mine are, you don’t agree, we reason that with those who decide and they make a decision. There is no data that will ever help them with that decision. Your logic is wrong.

Nor have you demonstrated different people are paying the costs. I have logically shown they are not – bar bankers.

We could debate that difference forever, but we are at a point where it is becoming meaningless to do so. You demand data. I can show that is not logically needed to make a decision. We are at an impasse.

Now, let’s move on. We’re going nowhere fast on this one – but you’ve certainly not knocked my arguments out

Richard

The nub of your argument seems to be: we don’t know what effect these changes will have and we cannot know what effect these changes will have. Therefore we must make these changes.

Does the phrase “a leap in the dark” have any resonance for you?

For myself, before we decide to change the taxation system for the globe’s financial markets I would insist that we should only be making changes where we can predict both the effects and the magnitude of them.

You’re quite right that in this case, you arguing let’s try it and see and me arguing that we ought to see before we try, we’re not going to have a meeting of minds here.

But the argument that change there must be, here’s a change so we must make this change, even if we don’t know the effect of such a change, isn’t the strongest one that I’ve ever seen.

Tim

Oh, I’m not saying I’d introduce it without more work. I’d do a lot more work.

And then at the end of the day it would still be judgement.

That’s the way it always is

But I do think much more work could be justified on the basis of what I’ve argued and you’ve not delivered any blows to it in my opinion bar proving a) I and others need a bigger budget and b) such decisions are not in the end empirical, because all empirical work is dependent upon the assumptions amde – and you and I do not make the same assumptions

None the less there have been pluses. For the first time I’ve enjoyed differing with you. Thank you

Second, you now need to return to my other questions

a) What’s wrong with my logic in the original post on incidence – and that cutting corporation tax will always increase it on labour?

b) How would you tax capital?

c) Why not unitary taxation and what is your objection to country-by-country reporting in that case?

You said you’d respond

Richard

1) If, as Joe Stiglitz pointed out can happen, the incidence of corporation tax on the workers’ wages is higher than 100%, then cutting corporation tax will incdrease the workers’ wages by more than the cut in corporation tax. Even assuming that taxes on labour are raised to cover the lost revenue (that no other measures are taken, such as different methods or taxing returns to capital, or spending cuts) as we don’t think that the incidence of taxation upon labout is more than 100% on labour then labour will be better off by being taxde directly rather than indirectly.

2) Not a problem I’ve particularly thought about. Not in the level of detail that we’ve been discussing the incidence of this FTT for example.

For entirely other reasons I’m very tempted by simply abolishing the difference between capital and income tax for the individual (although perhaps retaining an inflation allowance for capital taxation). Income is income however gained and you pay the same rate of tax on it. At the same time, entirely abolish corporation tax.

As I say, not wholly thought through but it is tempting. The economic distortions brought on by the corporate tax seem to me to be obvious….I’ve not seen figures for the UK but for the US there’s an emerging consensus that the tax yield of some $300 billion causes around that sum to be spent in trying to avoid it. That’s a deadweight cost of $300 billion which is substantial. While I disagree a great deal with a lot of your analyses I do agree that companies are more likely to change their behaviour, spend money on expensive lawyers, accountants and all the rest, to avoid taxation than individuals are.

And this is a second part of the tax incidence argument. Companies aren’t really paying the tax, they’re agents for those who do carry the burden. Given the distoritions and contortions those agents go through, perhaps, despite the convenience of using them as agents, we shouldn’t? Tax those who benefit from the existence of companies, not companies.

There’s a political reason why I don’t think this likely…..and it’s the same political reason why I like the idea.

The man in the street (and you yourself have taken a lot of convincing of this very point) believes that the company does indeed pay the tax. That tax incidence isn’t a valid argument (in fact, most have never heard of it). So to the politician looking for revenue the company is an easy target. For everyone ignores that the company doesn’t really pay it.

Militating against this idea of equal tax rates for income from any source for an individual is the idea that capital is more mobile than either labour or consumption. We probably therefore want to tax capital returns at lower rates than income.

So, as I say, not fully thought through. But as a first pass attempt I’d start with abolish corporation tax altogether, raise CGT and dividend taxation to income tax rates and then explore the implications of that.

3) I’m still very confused by your insistence that country by country reporting is unitary taxation. I take that latter to mean that there’s one tax rate on hte company’s activities wherever they are based. Yet you are adamant that each jurisdiction should be able to impose whatever tax they wish. So it isn’t, unless I’ve grossly understood the concept, unitary to my mind.

My second objection again comes from an economic concept, Coase’s theory of the firm. Why firms exist in the first place instead of simple contractual relationships. Coase said that sometimes simple contractual relationships are more efficient. At other times firms are. Your system of taxation, by insisting that the multi-national present itself as a series of arms length transactions, ie, as a set of contracts rather than the whole, seems to me to be taxing without understanding why firms exist in the first place.

[…] (yes I know it sounds surprising, but it’s also been true). At the end of it the best Tim could say was: For myself, before we decide to change the taxation system for the globe’s financial markets I […]

[…] (yes I know it sounds surprising, but it’s also been true). At the end of it the best Tim could say was: For myself, before we decide to change the taxation system for the globe’s financial markets I […]