As I mentioned in an earlier blog, I've been led to believe that the Institute for Fiscal Studies are having some difficulty with the criticisms I've made of their proposal that VAT be applied at one, standard, rate to the supply of all goods and services in the UK bar news houses.

My argument is that this change is regressive. I gather the disagree. They say that the poor can be compensated for the additional costs. More important for the purposes of this blog they argue that:

Abolishing zero and reduced rates of VAT would cut compliance and administration costs for business and government, interfere less with people's spending decisions, and raise enough revenue both to improve the living standards of poorer families and to cut other taxes by £11 billion.

As they also note:

[T]he authors are … advocating a reform to make VAT less distorting and welfare-reducing

It is obvious from the quotes that the IFS think this issue of distortion really serious. It is implicit in their criticism of the system as it stands now that in their opinion a tax system should not create distortionary impacts on consumer choice.

I do not agree with this position. Implicit in it is the assumption that the market efficiently allocates goods and services for maximum benefit when it is perfectly obvious that this is impossible given the unequal resources that people bring to the market, but let's leave that aside for the moment and presume that the removal of the distortionary impact of imposing VAT is the correct policy to adopt. My criticism of the IFSs' recommendation of a consistent VAT charge is that this does not eliminate that distortionary effect.

Let's start with a little theory. Let's assume there was no VAT. And then let's assume that VAT was to be charged at one flat rate on everything (we'll even add housing for now). If that were done the only circumstance in which the outcome would be consistent demand for all goods and services before and after the change would be that in which all goods and services had consistent elasticities of demand. Let me assure you: this does not happen in the real world. We buy some things almost irrespective of price: food is one of them. We can't live without them. We can live without fripperies. So the elasticity of demand for food is low, that of luxuries is high. This is why I gave one of my blogs on this issue the title I chose last week.

Now, assuming that the imposition of VAT on products is not fully and exactly compensated for all consumers (and the IFS do not propose this and there is in any event no way in which this could accurately be done, and the IFS do in any event explicitly think it undesirable) then in the face of reduced income (as most in income decile groups 4 to 9 will, I expect, suffer as a result of the IFS recommendations) then there will as a result of the imposition of this equal VAT and reduced income be a change in the profile of consumption. The goods with lowest elasticity of demand will now feature more prominently in the household budget; those with highest elasticity of demand will feature less. That's inevitable: all this means is that when prices rise and incomes rise less then it is the non-essentials of life that go by the wayside because the essentials, such as food and power remain just that, i.e. essential.

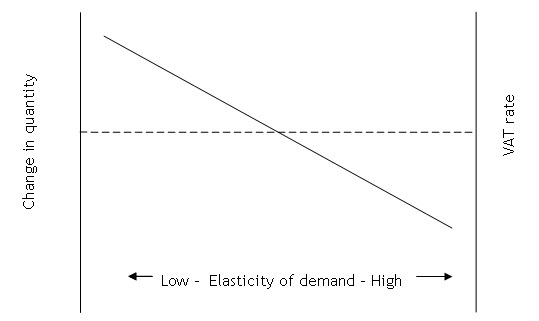

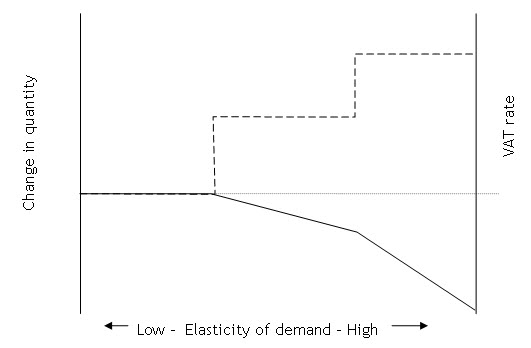

But in that case imposing an equal VAT is distortionary. The graph looks like this:

The sold line is the impact on demand, the dashed line an indication of the rate of VAT rate change across differing products.

In the face of a VAT increase relatively the quantity of low elasticity goods (food and other essentials) goes up in the consumer basket and of fripperies goes down. The horizontal dashed line represents the fact that this is the reaction to a flat rate VAT.

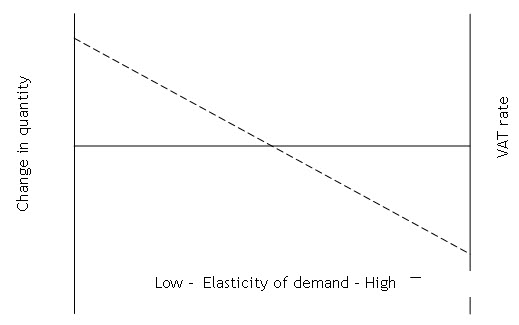

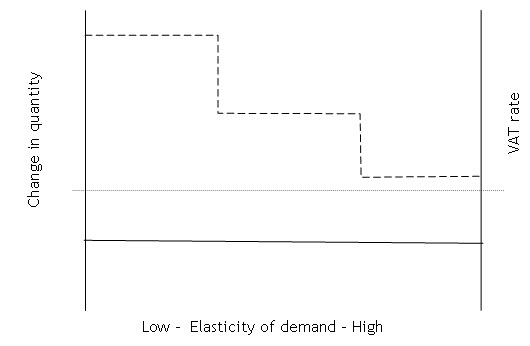

Of course, it is possible for a VAT to be introduced that does not have this result. In this case though the VAT rate would have to look like this:

This graph, which is the one that meets the IFS non-distortionary requirement does however not involve a flat VAT rate. Far from it. It requires that a high rate of VAT be charged on basic items and a low one on luxuries.

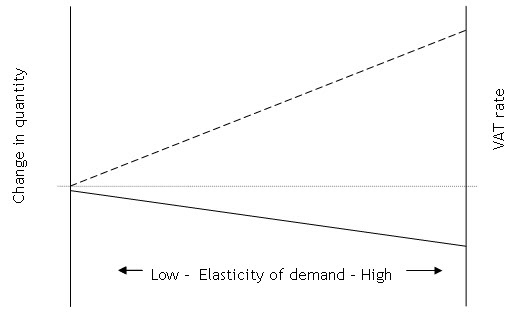

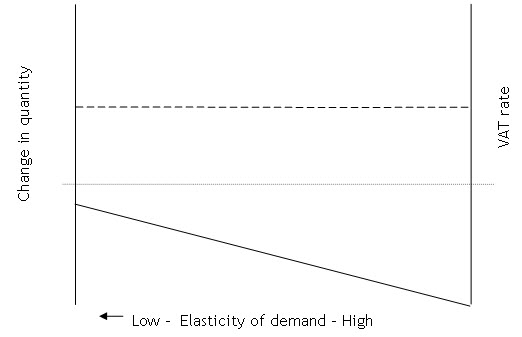

But, of course, those of us who worry about social welfare the need for those least off in our society to meet their basic needs think that VAT should be the exact reverse of this. Our chosen graph is:

An X axis has been added here for convenience. The VAT rate change on essential items is zero so their consumption does not change. It is highest on non-essentials: a fall in their consumption has very limited impact on well-being despite what the Sunday magazines tell you.

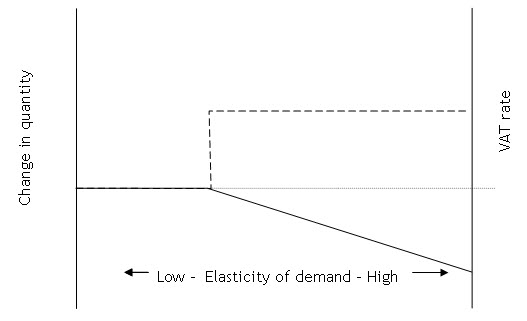

Actually of course this is impossible: VAT rates cannot be set at smooth increasing rates so the function I prefer would really look like this:

The VAT impact, impact and X axis all coincide at zero for essential goods and services with low elasticity.

It could, incidentally, and in my opinion desirably be argued that the function should in fact look like this, with a third VAT rate for luxuries:

In a world where excess consumption needs to be reduced for the sake of the environment I think the argument for such a 'luxury' rate compelling. It is, of course, not that radical either. This was the first model of VAT introduced by Geoffrey Howe and Margaret Thatcher, and it fairly reflects the VAT required by a person who wants that tax to provide minimum disruption on the well being of those least off in a society.

This model sharply contrasts though with the practical model that a person wanting no distortion of consumption in the market would want, which would look like this:

The non distorted consumption line is, of course, now an approximation at best.

Both these models have theoretical logic to them: both are actually logical. Neither looks anything like this model though, which is that which the IFS is suggesting:

Note that I show the overall welfare loss of this to be higher than my version of the model: I stress that's an assumption but I think it could be shown to be true.

The real question now becomes, why have the IFS chosen a policy option for which there is no apparent theoretical justification? I acknowledge: they do refer to this argument in their paper, but mainly with regard to goods such as beer and tobacco, but dismiss it in general. It is clear from the paper that this is a choice, and that the evidence for doing so is not unambiguous. In that case I do not understand why they did so when the best that this option can be described as is a compromise that does not achieve their aim.

If such a sub-optimal choice is put forward behind the veneer that it is better there must be a reason. That reason is not, as I've shown theoretical. So it must be political.

I'm not saying that's party political. I'm saying it's political in accepting a certain structure of society and the way in which it may be managed. In this case it's indicative of a frame of mind that thinks the argument for taxing capital has been lost, that thinks that government should be small, that markets are efficient, that well-being for all is inflated by tax cuts for some, and that social programmes must be of limited reach to ensure minimum impact on market outcomes, even if those do not accord with perceptions of social justice, which as a result are given low status in decision making. That is a political mind set.

It's to that issue that I will turn in my next blog.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Is the IFS making a political status? Production Efficiency (Mirrlees, 1971, AER) is the standard theoretical metric for tax efficiency. Broadly speaking, this suggests that an efficient tax is one that does not distort allocations of input resources – isn’t this what their suggestion does?

Jon

I apologise but I am genuinely confused as to your meaning. I do not think I am following the construction of your argument.

Can you try putting it another way?

Richard

Hi Richard,

We’ve recently published a post calling for a reduction in VAT as part of a package of measures now needed in the light of the current crisis – your piece is really interesting as to the way in which any cut could be structured. Many thanks

Damon