Danny Blanchflower and I had a fun conversation last night. It's always good to talk with him, even if most of the time we're two strongly opinionated economists swapping views separated by the width of a fag paper.

So we agreed there was no reason for a rate rise yesterday.

After which we agreed it must be egos or Brexit that drive it.

And we agreed that the fact that the decision was unanimous was deeply suspicious: groupthink has a dangerous history at the Monetary Policy Committee.

That said, we were unanimous that we'd have proposed a cut in rate to signal to the government that there is a strong need for fiscal intervention by them and that the Bank is out of firepower to deal with the issues we face.

So what is the biggest issue? We discussed this, of course. Growth at 1.5% and that the Bank now thinks that's overheating could be one such issue. When the economy is in need of the sort of transformation that only serious investment (and so, of course, continuing low interest rates) can bring them to have the poverty of aspiration that the Bank has displayed is dire.

But worse is their view on wage inflation. This is where Danny is the real expert. I doff my hat. So should Mark Carney. Danny, and his colleague David Bell, have a new paper out on why despite the fact that the world's economies are supposedly at full employment we are not seeing the inflation that the so-called Phillips Curve predicts we should be suffering.

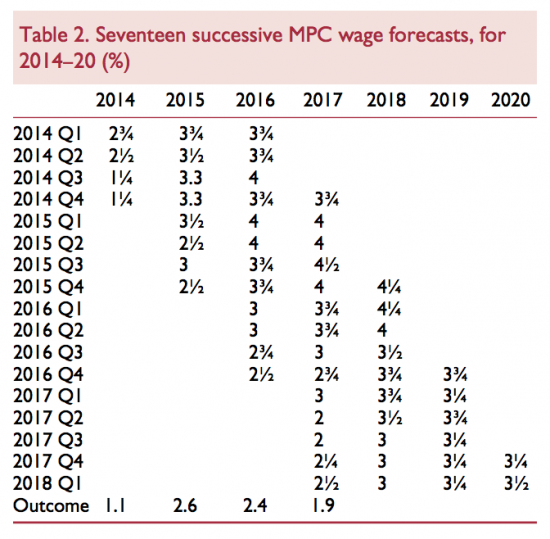

Danny's explanation (if I can summarise it) comes in just two tables. The first is this:

To not be too unsubtle about it, the Bank's ability to forecast on this issue is dire, as Danny and his colleague have shown. They persistently overshoot in their forecasts, and appear not to have learned any lessons from doing so. I entirely agree with Danny that this is happening now.

Danny and I also agree on the fact that the Bank is just wrong to maintain that we are near full employment. Both of us have done work on self-employment and the disguise it provides for under-employment in our time. I have no doubt this is happening now. In the same paper I have already noted Danny and David Bell look at the issue of underemployment being disguised by involuntary part-time employment i.e. those recorded as being in employment but who would wish for more hours than they are currently able to work, usually shifting them from part time to full-time work. This is a critical issue. And it is widely prevalent, as this (the second) table shows:

The implication is obvious: we are not at full employment, or in our mutual opinion, anywhere near it.

But that brought us to another theme, where again I bow to Danny's expertise. This is the so-called NAIRU - that is the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment. It's not that long ago that the bank thought this was 8%. Then it was 7%, then 5%. Now it's about 4.5% on their opinion. But why? As Danny explained, when researching a new book out next year from Princeton entitled ‘Not working: where have all the good jobs gone?' he looked at NAIRU since 1945. He says as a result that it's quite fair to argue that from 1947 to 1958 it was 1.5%. Of course the world has changed since 1958 (excepting the fact that's when I arrived in it). And the profile of employment has changed radically too. But why has NAIRU changed? Or has it? Could it be argued that it is now no more than 2.5%? I think that plausible. And, we agreed that NAIRU should be measured when those in employment have the hours they want and are being paid persistently, at a living wage rate (at least). If that's the case then for the Bank to claim we are at full employment now is as likely to be as wrong as their wage inflation forecast, on which we can place a near certain probability of overstatement.

To summarise, if Danny and I are right, and as I said, it was hard to find a point of disagreement between us, then the Bank of England are massively wrong in their forecasts on employment and wage rate increases. They are also wrong on growth, because they are presuming there is no capacity for it when that is just untrue. So what chance their inflation forecast is right? Near en0ugh none at all, if external factors are excluded from consideration.

But in that case what they have done is send out profoundly worrying messages. I mentioned some of these yesterday, but I will reiterate them.

First, they are sending out a message that they are out of control: they are issuing forecasts that do not accord with observable facts.

Second, they are making decisions on the basis of those observably incorrect facts that appears to be inappropriate as a result.

Third, that then undermines the credibility of a so-called independent central bank. It is well known that I have little belief in this idea in any event. But when they actually can't do their job properly any vestige of worth disappears.

Fourth, you have to then wonder what they are really doing (especially with 9-0 decisions for an idea as far off-beam as this one) and that fuels conspiracy theories. We could really do without more of them.

Fifth, whatever claims are left for monetary policy are shredded, but when fiscal policy is not (as yet) getting a look in that leaves it appearing that no one has a clue how to manage the economy. We are out of control.

And, sixth, as an economy boost before the inevitably of a poor Brexit (on which, at least, Carney was appropriately clear) this is a complete failure.

Worry. I reiterate that advice.

And look forward to Danny's book.

We have agreed we should talk more often: it's always fun, even if self-confirming. But I strongly suspect we're right this time. And it's good to be so in good company.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Very interesting.

When you said that the BoE of was out of control I thought that it was also out of touch as well.

What I’m seeing here in the public sector is people leaving and then other people picking up their work.

Any new people are being employed on short-term contracts but higher than usual wages. I also know that people who 3/4 years ago went self employed are still struggling to earn what they did in their previous employment which they left in the first place because of feeling they were not paid enough!

I’n not sure how higher wages/short term contracts count as some sort of gain to the economy – as one cancels out the other in the long run. What we need is job stability and sustained income improvement.

I go back to the point I made yesterday: Who is the BoE REALLY speaking to when they made this decision. Who benefits really?

I wish I knew…

There’s an old saying that if it ain’t broke then don’t try to fix it. We’re in the 2nd longest period in our history without a technical recession so why start changing things up on interest rates? Like you, I just don’t get it. I don’t think it’s vanity. You can go back and read the minutes from when the last time the rate was raised and I’m sure that you have. Compare them to the minutes from yesterday and it’s clear that it wasn’t vanity at work yesterday, so something else is clearly going on. And in a group of 9 people, if vanity is at work then at least one will break from the consensus so at least he can say ‘I told you so’ when it all goes wrong, rather like Danny Blanchflower did back in the late 2000s when he voted for cuts when everyone else was arguing for the status quo.

It can only be a neoliberal plot.

Increasing the bottom line for those businesses involved in lending is rarely mentioned as a hidden and corrupt pressure to raise interest rates and consequently one reason for not giving your central bank independence.

Nice work from you two. Couldn’t agree more.

Here’s my question;

Where is that great bastion of rational, evidence-driven, left-leaning economic thought at the BoE, the person so many people look to for guidance and an antidote to remorseless neoliberal ideology? The Chief Economist of the Bank of England. Where is Andy Haldane on all this, hmm?

Voted for the increase….

In three days time it will be my fourth anniversary of being made redundant. One interview in 2017 and none this year despite thirty years of IT experience. If we are at full employment this shouldn’t be the case should it? One of the few things I remember from my A Level economics is that “full-employment” means anybody who wants a job can get one. If you have a bad employer or don’t like your current position you can just move. Easy peasy. Not.

Leigh

I’m awfully sorry to hear that you were made redundant.

Where I work (in the public sector) we reckon we will be lucky if we get another 10 years out of it – if that – the way things are going. Just enough time to get the kids through Uni and pay off the mortgage.

What a way to live.

Thomas Palley’s recent paper needs to be read because the old idea that globalisation is still about comparative trade is dead it’s about globally roaming capital trying to get a lions share of income at the expense of labour:-

https://www.boeckler.de/pdf/p_fmm_imk_wp_18_2018.pdf

The BofE’s economic analysis may be, as you suggest, eccentric (my brief, gentle interpretation of your argument); but it appears to me that it was Brexit that was primarily on Carney’s mind (he used the term ‘Brexit’ no less than 12 times in his opening remarks at the press conference; not indicative of an ‘aside’).

Let me try to folllow this through; for brevity allow me to focus on one (scarcely unimportant scenario, that I would expect the BofE must factor in): if there is a ‘no deal’ Brexit, what then? BofE policy choices may require to move in the opposite direction. In short, will the increase in rates quickly be overturned and rates reduced; and at what cost to the BofE and its monetary policy committee’s credibility? In short, why do this now, at the point of maximum uncertainty over Brexit (to say nothing of the UK’s credibility)? What is the agenda here?

I hate to say it, but I am told he covered this on the Today programme this morning

I was not listening

It has just been rreported that Mark Carney has now said that the prospect of a ‘no deal’ Brexit is “uncomfortably high”. Why not make that observation yesterday; why not factor it into the rate rise decision? Why raise interest rates yesterday? What on earth is the strategy? Is there one?

No

But it makes yesterday even more incoherent

MMT 101

Interest rate hikes fuel inflation they don’t fight it Richard.

Your point is?

Given I suggested a cut?

How do you class yourself as an ‘economist’ given you have no formal training?

Maybe because I am Professor of Practice in International Political Economy, City, University of London

It’s interesting that you think they are remotely the same.

They are

In which case why are you not part of the Department of Economics?

Because I am not an econometrician and that is all that departments of economics now teach

I am also not a neoclassical economist, and that is a virtual precondition of employment in such departments now

You really do have a lot to learn

Given that you appear to disagree with the vast majority of mainstream economists out there, what does your claim to be an ‘economist’ actually mean?

You clearly do not know that almost all economists disagree with each other

It’s the surest evidence that there is that I am one

It means I have integrity

Unlike a person who has posted here under at least five names, as you have