I wrote a blog yesterday suggesting that despite the impression given by law and practice direct taxes, such as corporation tax, are not in fact taxes on profits, as is implied by their description, but are in fact taxes on specific transactions. The inevitable adverse reactions were received, suggesting that I had, as usual, got everything wrong. Since this is, however, the inevitable reaction of those with a vested interest in the existing system on every occasion that was to be expected, but in practice the comments made suggested to me that if anything my theory is closer to the truth than I had expected.

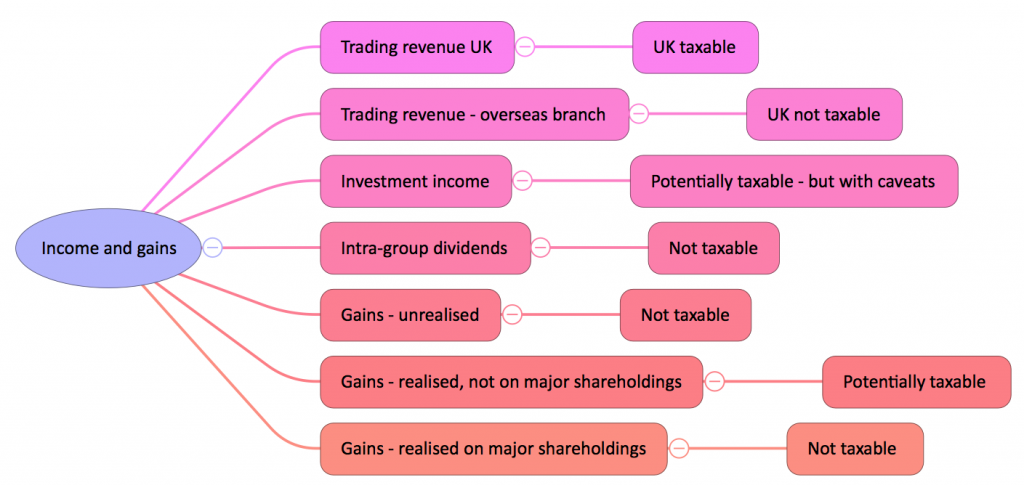

As example, let's just look for a moment at the potential sources of revenue for a UK company. This diagram helps:

The revenue of the company, by no means all of which will be reflected in its turnover, but all of which will, eventually, contribute to its profit, can come from a wide variety of sources, some of which are noted above. And, as this simplified diagram notes, quite a range of those revenue sources can, even though they give rise to what are described as realised profits (that is, cash in the bank) give rise to no UK tax liability.

I stress, that is not because the profit is outside the scope of tax: it is because the source of income is outside the scope of tax. So, for example, dividends received by one UK company from another UK company are not taxed, and this now applies to intra-group dividends received from companies outside the UK. Similarly, the proceeds of sale of significant shareholdings by one company in another company are not subject to any tax, even though they can give rise to significant capital gains. Most tellingly, revenue now earned by an overseas branch of the UK company is also outside the scope of UK tax.

Many of these exemptions ( or loopholes, if you like, for that is what they are) are recent innovations and only a very few ( such as the receipt of dividends from other UK companies) have any obvious theoretical justification. The distinction between realised and unrealised gains is also new: this aberration, which has fundamentally undermined the reliability of all financial statements, basically dates from the adoption of International Financial Reporting Standard as the de facto accounting standards for the UK in 2005.

The reality is that when corporation tax was introduced I think it was, as the law describes, intended to be a tax on profits. The fact is that this is no longer the case: we now have a tax on specific transactions undertaken by companies, less the costs that are allowed by law to be offset against them. That is something very different indeed but what it does do is open the opportunity for those with an interest in tax policy design to ask some very relevant questions. These include the very obvious ones, such as why have we chosen to exempt those types of income for the currently untaxed, and should we reform that approach? Likewise, the opportunity to ask about the costs that should be offset against taxable revenues is now very clearly within the scope of policy debate.

Once the linkage between profit and tax is broken, as I think it has been in the case of corporation tax, and to some extent income tax, them we need to look at the whole basis of tax design again. It is something I intend to do because the opportunities that this opens for the taxation of what might be described as 'bads' whilst exempting those transactions that we think to be of benefit to society is one that is too important to miss.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

Setting aside its impact on usefulness of Financial Statements, the realised/unrealised distinction does actually make sense on the ground when running a company. I well remember an FD whose response to the idea of being taxed on unrealised Forex relating to intragroup balances was “colourful”.

I’m not saying it is not useful: it may even be real, but its differentiation for tax is key and shows not all profit is taxed

I’m not sure there is a logic in taxing the unrealised ‘profit’ on ie Forex – say you have an unrealised book profit of £500 in year 1; you pay tax at 20% of £100, but you have to magic the cash up out of somewhere because neither the bank nor anyone else has put it into your account. Then in year 2 you get a corresponding loss of £500. Your tax bill will (hopefully) be £100 lower, evening out over time.

But, your cashflow has suffered. Especially compared to a business with the reverse loan; they got a cashflow boost. And what if the gains or losses run for several years – ultimately you end up paying (or not paying) loads of tax on a pure paper fiction; precisely the sort of thing that measures such as UT are supposed to try to prevent?

I have not asked to tax unrealised profit

Good! Sorry if I misunderstood; it was something I’d deduced based on the description of the distinction between realised/unrealised gains as an ‘aberration’; I assumed you were suggesting consistent treatment for both, and realised gains should of course be taxed…

But yes, I can see within the premise of taxing transactions rather than ‘profits’, unrealised gains can fall out twice: once on policy grounds (as per the earlier comments), or alternatively if you decide that they aren’t really ‘transactions’ at all as there’s no ‘economic substance’ (for want of a better term) going on.

I think most of the areas you have highlighted were introduced with an obvious reason and purpose in mind.

Dividends are are a distribution of profits after tax so corporation tax has been paid on the profits from which the dividends are derived before they are paid out. So if they are taxed on receipt as well, the same money will be taxed twice. An underlying principle of tax around the world is that income/profits should only be taxed once. The extension of this to non-UK companies was forced on the government by EU anti-discrimination law.

In respect of the sale of significant shareholdings I assume you are referring to the Substantial shareholdings exemption which was introduced to allow company’s to reinvest the proceeds of sales to create jobs, more taxable profits etc to encourage economic growth.

The recent changes in respect of the income from overseas branches is more of a simplification. The taxation of this type of income has in the majority of cases not been taxable, either under the relevant double tax agreement, or has been offset against tax paid overseas for decades. The simplification was merely to recognise this fact and to cut down on unneccessary red tape and reporting.

I would also suggest that the distinction between unrealised and realised gains has always existed, although IFRS has made it more complicated.

The UK now has the longest tax code in the world and we need to simplify it rather than make it more complex. The companies/businesses in this country generate jobs, wealth and income for this country, most of which is taxed at some point through the multiplier effect. We need to stop trying to squeeze more tax out of them for the government to waste.

What we should be focusing on is how our taxes are used and reducing the ‘criminal’ wastage of money by the government, both at local and national levels.

I admit that I could offer extensive commentary on what you’ve written, but candidly it is so obvious that I do not agree with most of what you’ve written, much of which is simply an exercise in offering excuse to tax avoidance, that I can’t be bothered.

Your political bias is also clear but provides very obvious evidence of completely blinkered thinking. It was, of course, the private sector that crashed the economy in 2008. That is where the criminal waste of money took place.

I always find it very strange that whenever those who oppose government spending get into office they immediately find it very difficult to identify any significant cuts. there is good reason for that: whilst the government is undoubtably inefficient, as all systems are, it is quite probably less inefficient than most private sector operations, but those who are blind to this for reasons of dogma will never agree

I have no political bias.

I agree elements of the private sector contributed to the crash but just to blame it on the private sector is an over simplification.

I am sure you are aware of the wastage on government procurement contracts which is well known and well documented.

I thoughts your blog was a debate on tax and not just a forum for you to insult people who may have a differing point of view.

But I guess I was wrong, so I will not comment any further.

With the very greatest of respect, for you to claim that you have no political bias is one of the more absurd comments ever put on this site.

Let me also note the absurdity of this new comment on procurement. Why is it that you blame government for this failure? Isn’t the deception wholly on the part of those companies who claim that they can provide a service and then fail to deliver? Why isn’t that where your attention is focused?

I’m very happy to engage in debate, but I do expect those who offer comment to at the very least be honest about their own position and to add value by the observations that they make and your comment makes it very clear that you are not. In that case you will save us both a lot of time by not commenting again.