I was challenged when recording Hecklers for Radio 4 recently to estimate the tax lost as a result of the UK's domicile rule. And I admit I guessed. I said as much must be lost as was paid by those officially registered as having that status.

According to Jane Kennedy at the Treasury, that's about £3 billion a year. She says that the 112,000 registered non-domiciled people have an average income of about £87,500 a year and pay about £26,800 each in tax, a sum which almost coincides with a simple calculation of the liability due by anyone on that income.

This information did not, of course, suggest anything about tax lost, only about tax paid, so I thought some more calculations might be in order. So I went to table 2.5 of the HMRC statistics for 2006-07, the last year for which there is real data.

Using data solely in that table I could work out the average income of people in the various income bands it refers to and the average tax they paid. In the income band from £50,000 to £100,000 the average income is £66,452 and the average tax paid is £16,581. This income is obviously a lot less than that of the average non-domiciled person. But they do fall into this band as a whole, on average. That locates them for the purpose of this analysis.

Claiming non-domicile status is, of course, of no benefit if you have no income or gains arising out of the UK. So, it logically follows that those who claim this status must have higher income than that which they declare in the UK. The data disclosed by Jane Kennedy clearly refers to the income these people declare in the UK. Since their average income is already £87,500 it's reasonable to assume two things.

The first is that their real income is going to be, on average, in excess of £100,000.

The second is that because of their ability to use the domicile rule they don't on average appear in the data relating to those falling into this income bracket as published by HMRC in their table 2.5. In other words, statistically they do not significantly distort the data for those who declare income in that band and above and as such it is statistically acceptable to base an analysis on that data set and to extrapolate it to calculate tax lost without having to allow for the presence of non-domiciled people in that data set.

I stress these are important assumptions. I also stress that I think that they are fair.

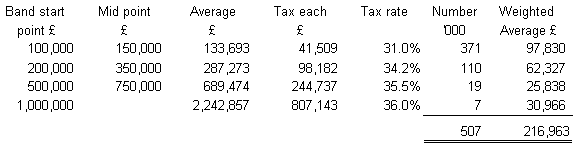

There were 507,000 people in the UK who declared income above £100,000 in 2006 - 07. Data on them might look like this based on Table 2.5:

The average tax rate in this group is about 33%. To be more precise is to add spurious accuracy. The weighted average of their income is £216,963. So, the average tax payable might be £71,598. If UK tax rates were applied as set out in law the tax payable would be more: I'll live with the compromise and assume tax reliefs and planning takes place as the figure I use implies, and as would be likely in practice.

Given that all 112,000 people who are non-domiciled should on the basis of the assumptions made fall into this income bracket, but do not at present, we can extrapolate this liability to suggest that if those non-domiciled people did declare their likely average worldwide incomes here (assuming they are distributed in the same way as those of UK domiciled people, which seems if anything an assumption likely to underestimate their actual liability) then their total tax liability would be £8.019 billion a year. But we have been told that the tax paid by non-domiciled people in the UK is just £3 billion. This suggests there is just over £5 billion of tax unpaid as a result. Logically this has to be true.

But logic is not, of course everything. It's been argued that some non-domiciled people will leave if the domicile rule goes. However, since many work in the City of London that's unlikely. There's nowhere else for these people to go to get the experience they want assuming they can't or don't want to go the States. They'll stay. So will all US citizens now here. They pay US tax on their worldwide income anyway. And all those who are not domiciled here but who are in the UK because it's a great place to do business stay. As will all those who would pay more tax if they lived just about anywhere else in the world that charges resident people to tax on their worldwide income and also provides a decent environment in which a sane person would want to live (which excludes most tax havens, for starters). But, let's say 20% of all non-domiciled people decide to go as a result of a rule change to allow for the argument of those who say this would happen. Then the total tax paid by this group would go down to £6.4 billion. That still leaves an apparent gain of £3.4 billion from getting rid of the domicile rule.

But there are two further taxes that must be considered. One is Inheritance Tax. Non-domicile people are older than average when they make their claim for this status. And they do die. Those that do will, if the domicile rule is abolished, fall within the net of this tax. Most do not now. Suppose just 2,000 non-doms a year will die here. Their estates are highly likely to be chargeable. 37,000 estates are chargeable on average a year now. If these estates just paid the same as each of these on average the tax yield would go up by £215 million. A much higher yield is likely.

And also consider capital gains tax. In 2006-07 the total yield from this tax was £3.8 billion. This would have been very largely paid by people earning more than £100,000 a year: they have the cash to invest in assets that result in chargeable gains. If the population chargeable to this tax went up by 80% of 112,000 then the yield would increase by 17.7%, or about £670 million. In combination with Inheritance Tax that is £785 million extra tax a year.

Add to that the fact that 112,000 is the number currently claiming to be non-domicile. As has become clear as a result of the recent UK 'tax amnesty' quite a number of those who have not declared their offshore income have not done so assuming they were non-domiciled but without having told the Revenue of that fact. 60,000 people have so far come forward under that scheme. Suppose 20% of them use this defence then 12,000 extra people will fall into the net if the domicile rule goes. To be cautious suppose they aren't as wealthy as those who have declared their non-domiciled status and only, on average, have extra tax of £20,000 of income a year to declare (I gather that this is not uncommon amongst those making declaration). That's £8,000 of tax each. That's £96 million extra income tax. And another £90 million of potential capital gains too, which is reasonable because non-domiciled people find these very easy to avoid at present.

So now we have (within reasonable grounds of estimation) almost £1 billion of extra tax to compensate for the losses from those who leave. That brings the extra income arising from the abolition of this rule to a sum in excess of £4.3 billion calculated with caution throughout.

Can the UK afford to ignore this extra income? I doubt it.

Will it lose anything by the change? Candidly, no. The City will still handle the same people's money. Non-domiciled people will be able to remit all their income and gains here without restriction: the VAT yield will likely go up as a result. And will business go? No, of course it won't. Business locates where there is profit to be made and the UK provides ample opportunity for that.

The gain is there to be had. It will just take political will to claim it.

And for those not sure what the domcile rule is, this video might help.

Thanks for reading this post.

You can share this post on social media of your choice by clicking these icons:

You can subscribe to this blog's daily email here.

And if you would like to support this blog you can, here:

I think the non-dom rule is a bad idea, even regardless of the tax it costs the UK. It’s somehow morally questionable in itself.

[…] I’m pleased to have been able to supply that estimate. I’m as pleased with the use being made of it: linking the domicile rule and child poverty seems to me to make clear the obvious fact that tax abuse costs real people real money, money that could be used to improve the real lives of many at limited cost to few. […]

[…] What more do you need to know, Richard? The answers are all available here and here. The rule has to go. […]

[…] Actually, the calculation wasn’t that hard. It’s based on the available evidence. All that I know of. Of course it includes estimates and assumptions, that’s the nature of these things. But I have been transparent about what they are. […]

[…] Your officials have costed the elimination of child poverty at £4 billion. I estimate the gain from abolishing the domicile rule at £4.3 billion […]

[…] I’ve got news for George Osborne. The average tax paid by a non-domiciled person now is £26,800, based on Treasury data. So far from funding Inheritance Tax he’s actually planning a tax give-away. […]

Shadow Chancellor proposes a flat £25,000 tax for non domiciled residents…

It has been reported by Bloomberg that Shadow Chancellor of The Exchequer, George Osborne is proposing a flat £25,000 levy on UK Residents who are not domiciled in the UK. He is quoted as saying that “You can either register……

Richard,

I think there’s a fallacy in your reasoning here.

You start off with the Treasury figure that the average UK taxable income for a non-dom is £87,500 per year, and then assume that their real average income (including offshore) is over £100,000.

That’s probably reasonable as an average (although there are a lot of non-doms working here, with good jobs but not wealthy, with only a few thousand pounds of non-UK income).

You then say that “all 112,000 people who are non-domiciled should on the basis of the assumptions made fall into [the £100,000 plus] income bracket”, and then you use the HMRC figures for the average tax paid by someone earning over £100,000 to calculate how much tax they should pay.

That’s where you go wrong. You’ve given a reasonable argument that the average non-dom has worldwide income of £100,000+, but mathematically that means that at least half of them will have incomes less than that – leaving many non-doms legitimately in the £50-100,000 band.

There are some very, very wealthy non-doms, so to justify claiming that they all (or even nearly all) have true incomes of over £100,000, you would have to show that the average is much higher than £100,000.

You’ve not shown any evidence for that. Indeed with an average UK income of £87,500 – and therefore most earning less than that – you would need some very strong evidence to justify a claim that they all have true income over £100,000.

A lot of non-doms are just employees; yes they’re working in the City and earning good salaries, but they aren’t wealthy in the sense of having lots of offshore investments to generate high levels of non-UK income. An employee with a salary of £50,000 is unlikely to also have £50,000 of investment income, and the average non-dom UK income of £87,500 suggests that a lot of them are in that category rather than the super-rich.

Richard

(PS – I think you’re right that the Tories’ tax plan will generate a lot less than they claim, and my argument here reinforces that)

Richard

I accept we can argue the maths of averages – and it’s fair to do so.

I amde a choice for good reasons.

A) There are about 7 million non doms in this country. Only a tiny proprtion claim it. They must have good reason to do so. That is wealth. The sample is not therefore as skewed as you suggest. It is biased upwards.

B) There is only benefit when tax saved exceeds costs – and I can assure you getting the remittance basis right requires serious advice, accounting and tax help. If you suggest otherwise I respectfully suggest you’re misrepresenting reality. So My leap to £100k is justfied for that reason.

C) There’s no point in claiming unless there is serious reason for doing so. Again, this justifies assuming significant other income.

You may well be right – there may be hoards of lower paid non-doms benefiting a little – but they’re actually tax evading as they’re not reporting the fact and that’s illegal. And they’re not in the stats either.

Richard

Richard,

A) The £87,500 figure, and hence your £100,000 figure, is just those who are claiming non-dom status. Given that we know that there are some VERY wealthy non-doms, then mathematically most of even the declared non-doms MUST have UK earnings below £87,500.

You therefore can’t assume that almost all of them will have worldwide incomes below £100,000.

B) It’s only costly if you want to actually bring your money into the UK without it counting as a remittance. If you’re genuinely leaving it offshore then you don’t need expensive advice – in which case claiming non-dom status is cheap and easy.

I’d say that if you’re not trying to make disguised remittances, and you’ve got more savings than you can fit into an ISA, it’s worthwhile for any higher-rate taxpayer who can make a reasonable claim to be non-dom.

(I do worry about your old clients, given that you automatically assume that non-doms are trying to make disguised remittances)

C) – see B.

I think it’s reasonable to accept the Treasury’s new figures that the majority of registered non-doms have fairly modest amounts of offshore income.

Therefore to get serious amounts of tax from the non-doms you are going to have to succesfully soak (and retain) a small number of the very rich, many of whom could fairly easily go non-resident under the 183-day rule.

Richard

Sorry – 2nd para – ABOVE £100,000, not below.

Richard

Of coruse some jhave Uk income below £87,500, But it does not follwo that their world wide income is below £100,000 as a result. We know that income is always higher. The assumption is logical.

Your answer B simply reveals a lack of experience of the practicalities of remittance.

And you miss my point. I don’t care if the mega rich leave. I do care about the democratic credibility of the tax system. And as they don’t pay anyway, and only cause harm in our economy so what if they go?

Richard

Now, don’t get tetchy Richard.

It’s not just that SOME people claiming non-dom status have UK income below £87,500, it’s that MOST must have (since that’s the average and we know that some have VERY high incomes).

Your calculations are based on the assumption that ALL of them have worldwide income above £100,000. Since most have UK income below £87,500, that’s a very big assumption (even if it’s just “almost all”) but you’ve given no evidence to support it.

To bring income up from £87,500 to £100,000 would need offshore investments of about a quarter of a million pounds. And that’s just for the average registered non-dom; someone with a UK salary of £70,000 would need half a million pounds of offshore investments to push their income up that high.

That level of investment on that level of salary is going to be unusual, but your figures only work if you assume that most people claiming non-dom status are in that position – UK income below £87,500 but with massive offshore investments.

You may be right, but we’d need some pretty strong evidence before taking such a claim seriously – especially since you’re challenging the Treasury’s figures.

As for remittances, of course I don’t dispute that there are some very wealthy people who are managing to bring money into the UK without falling into the definition of remitted income.

However that doesn’t mean that there aren’t plenty of expats working in Britain who just have a few investments outside the UK and genuinely don’t remit the income.

OK, if you don’t care whether the mega-rich leave, why are you doing all these calculations in the first place? If they’re going to go, and you don’t mind if they go, why does it matter how much tax they would theoretically pay if they stayed?

Richard

Because

a) Most non-doms won’t leave – I’m sure of that

b) If they stay I want their tax for the beenfit of this country and its people

c) I care about justice

d) I care about democracy

e) I care about equality before the law

I could go on. But isn’t that enough?

Richard

Richard

I’m not being tetchy. I’m simply suggesting you’re being naive.

Non-doms can divert quite a lot of income and a lot more gains (which are in my caluclation) offshore and do not need anything like £250,000 to do so – simply registering a UK buy to let in an offshore entity could readily achieve this goal.

And let me now challenge you. What’s your number? Can you do better? If not, why not concede?

Richard

Richard

Agreed on (b) to (e), just very doubtful about (a) – and therefore the practicality of achieving the others.

Your overall figure may well be correct (wasn’t £5 billion also the guestimate Grant Thornton came out with a while ago?).

But I’m challenging your calculations, because I don’t believe that there are that many non-doms with significant offshore investments. I believe the Treasury’s figures that the bulk of the offshore income is in the hands of a very small number of very rich people

That’s important, because I don’t think the super-rich will stay around to be taxed. Sure they’ll still live here, but they’ll be non-resident rather than non-dom.

Richard

Richard

I accept that point – clealrly some will stay as non-resident

Bring back the rule that if you have a property permanently available for your use then you’re resident then, I say

Richard

But you have forgotten that many foreign jurisdictiond have double tax treaties with the UK. So, for example, a US citizen will be taxed on their worldwide income, and that tax paid in the US can to a great extent be set off against a UK tax liability, substantially reducing it. Also. a non-UK domiciled spouse has a spousal inheritance tax exemption limited to £50,000, not unlimited like a domiciled spouse. So, on becoming domicied, the UK will lose tax at 40% on the other £250,000 assuming it is liable to UK inheritance tax – thpugh I would say that this is an inequity that needs to be removed. Still, it upsets your tax calculations.

Many non-doms will have perfectly legitimate pension funds in their home country which benefit from tax-free arrangements like UK pension funds. But these may no longer be sheltered from UK income and CG tax as would a UK pension fund simply because they are not UK authorised pension arrangements. I thought things might improve when we got rid of Messer Brown. But now we have a choice of Messer Darling or Cameron – they should both take time to consider informed advice on the full implications of their proposals – and not base them simply on what might sound good to the vast majority of uninformed voters – and most journalists – on an election platform.

Respectfully Philip, yours seem to be the uninformed comments. Or special pleasding for privelige.

And I note you conveniently ignore tax havens

Richard

[…] No lets assume that tax planning by individuals increases the gap. I have shown that the domicile rule costs £4.3 billion. Let’s very modestly assume that all otter planning contributes no more (and this is very generous). […]

Richard,

Thanks for your respectful comment. I’d like to know on which of my comments your consider me to be uninformed – I speak from personal experience, which does not include tax havens, hence their omission. My wife happens to be a US citizen, and having done our tax returns for both jurisdictions for the last 25 years, I have learnt a bit about this – but I’m not claiming total knowledge. That said, we have both worked worldwide for most of our careers, most of it in non-pensionable employment in developing countries, often in the aid sector. Our joint savings from an abstemious lifestyle are sufficient to provide a retirement income typical of most professionals, but by no means large – shall we say, similar to Mr Darling’s proposed flat fee of £30,000 a year. We are not fat cats or tax dodgerd. Non-doms are generally taxable in the country where the income originates or in the UK as part of an aid agreement, which seems pretty fair to me. But most tax treaties are biased in a way that results in the total tax bill being larger than would be payable in either country alone, and that doesn’t seem fair. Remember too that ‘invisible earnings’ come from people like us just as much as from city bankers. I am quite happy to pay tax once in the country of origin and remit the balance to support myself and, indirectly, the UK balance of payments, but to find that I will be taxed some more just because a politician wants to drum up some votes and doesn’t understand what he is doing makes me angry. Mixed nationality couples put their savings in their country of nationality since that gives the most favourable treatment for pension savings for that person. Such arrangements are often not recognised in other countries, and so become taxable. I’m sure you have a few tax advantageous pension funds awaiting your retirement – why shouldn’t I? We would like to live together in retirement in one of our home countries, so one of us, at least, gets caught by the uninformed legislation of the kind we have just seen. There has been far too much legislation with unintended consequences. I would just like to see a less blunt instrument used to solve a relatively minor area of tax law which is abused by some people. If the tax revenues need boosting that desperately, why not make a serious attempt to stem benefit fraud. The amount raised would make the non-dom revenues pale into insignificance. But there are too many benefit fraudsters with votes, so I suppose thats a non-starter !

Philip

I was almost taking you seriosuly until I read your comment on benefit fraud.

And after that I don\’t.

Domicile abuse has been a massive issue, and an enormous abuse. Everyone in the UK has the rigfht to expect all people who are resident in the Uk to pay tax on a level playing field.

No one will have to pay the £30,000. You will not be taxed more than is required of others in the UK.

If this causes problems for a few, I am sorry. That is a net welfare gain. That is appropriate, and proper.

Whilst I will never condone fraud of any sort your comments on benefit fraud do show the lack of coherence in your argument. As I have shown today the tax loss in the Uk makes benefit fraud almost entirely inconsequential and not worth chasing in comparison.

And your contempt for democracy is beyond comment.

Richard

Richard,

You are probably right about benefit fraud. According to DPW website. benefit fraud costs the UK taxpayer in the region of £700million a year, though that may only be the fraud they know about. Of course, benefit fraud is fraud – claiming non-domiciled status is legal. If you want to enter into a debate on whether what is legal is also necessarily moral and vice-versa, we might find we agree to a great extent. You admit that US taxpayers already pay tax on their worldwide income, so if the Double Tax Treaty works, they may actually pay little more tax in the UK, just as UK citizens can exclude most of their non-US earned income from US tax. So your tax yield calculation is optimistic. Now suppose that, while maintaining your UK business interests and drawing an income from them, you went to live temporarily and work in another country while remaining resident for tax purposes in UK. Would you be prepared to pay tax to that country on your UK income while also being taxed by the UK on your UK income and any income earned abroad. That is basically what you are advocating. Use of tax havens doesn’t enter into this scenario.

[…] 4. Why didn’t he just abolish the rule and raise £4.3 billion in extra tax to tackle child poverty – about which he claims to be so concerned and for which the TUC have argued? […]

While in general I agree with your points, you are incorrect in saying that the new regime will not significantly affect US citizens. While we already pay tax on worldwide income, there are a number of areas where the tax systems are not aligned and therefore there will be double taxation. For example 1) I effectively pay no income tax in the US on my salary because the tax rate in the UK is higher – in part because I can not deduct mortgage interest in the UK but can in the US. However, when I recently moved house, I owed no tax on the capital gain in the UK but did owe capital gains tax in the US (and further income tax on the currency “gain”) even though I reinvested the proceeds into a new house. There was no way to claim the excess(from a US perspective) income tax paid on mortgage interest against the US tax on the gain. 2) Like most Americans, my pension is in the form of a 401K. This is not taxable in the US until I retire but is not a recognised financial pension in the UK and therefore the income in this account would be taxable in the UK. Similarly I can not take out an ISA or reduce my UK taxes through other means available to UK citizens because the US does not recognise these as deductions. 3) If taxed in the UK on worldwide income then I can no longer have a part of my savings in Treasury Bills (whose interest is is tax free in the US) because the interest would be taxable in the UK. Similarly I can’t have savings in gilts (not that this would make sense for an American anyway) because the income is taxable in the US. Given these discrepancies and the sheer complexity (e.g. how do you handle currency exchange factors to calculate the capital gain vs. the currency gain/loss on shares of GE bought through a quarterly reinvestment of dividends over ten years) the new charge is in effect a tax hike for American citizens. It is only a question whether the cost of compliance (i.e. accountants time) plus the cost of the added tax due to a lack of synchronisation in the systems is more or less than the net effect of paying £30k per year (actually £50k if you have to remit additional income to the UK to pay the extra tax and £100k if you count my wife as well). Furthermore I am being advised that the £30k could only be claimed against US taxes if I moved all of my savings out of the US (in order to generate ex-US income against which to apply the additional tax). While possible, this makes little financial sense for someone who plans to return to the US.

Peter

Respectfully, this seems to be a complaint that the UK does not tax in the same way as the US.

Is that really a fault or an issue the UK should address when the US tax code is known to be the worst in the world?

Richard